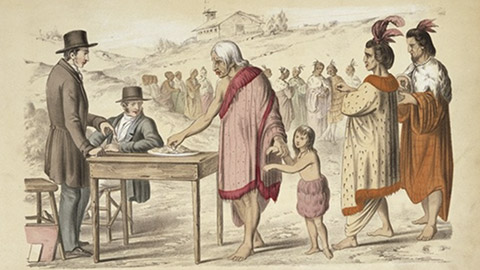

The Treaty of Waitangi | Te Tiriti o Waitangi is the founding document of New Zealand. It is an agreement entered into by representatives of the Crown and Māori iwi (tribes) and hapū (sub-tribes).

The treaty was created because of the needs arising from the settlement, land transactions and unruly behaviour of new arrivals; but was hurried along because of French interest in New Zealand.

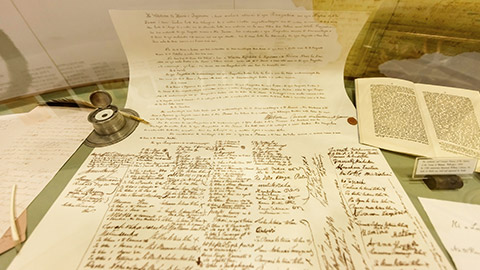

The Treaty was prepared in just a few days. Missionary Henry Williams and his son, Edward, translated the English draft into Māori overnight on 4 February 1840.

About 500 Māori debated the document for a day and a night before it was signed.

On 6 February 1840, the Treaty of Waitangi/Te Tiriti o Waitangi was signed at Waitangi in the Bay of Islands by Captain William Hobson, several English residents, and between 43 and 46 Māori rangatira.

Why did the British Crown want a Treaty?

The British Government was considering establishing a form of civil government in New Zealand because of the increasing number of British people arriving to live in New Zealand. However, a plan for private settlement by the New Zealand Company forced the British Government to act. The government instructed Captain William Hobson to act for the British Crown in negotiating a treaty because it was necessary to obtain Māori consent before establishing any form of government.

Signings throughout the country

After the signing at Waitangi, the Māori text of the Treaty was taken around Northland to obtain additional Māori signatures. Copies were also sent around the rest of the country for signing. By the end of that year, over 500 Māori had signed the Treaty. Of those 500, 13 were women. The English text was signed only at Waikato Heads and at Manukau by 39 rangatira.

Versions of the Treaty

The Treaty in Māori was deemed to convey the meaning of the English version, but there are some significant differences.

In the Māori version, the word ‘sovereignty’ was translated as ‘kawanatanga’ (governance).

- Sovereignty: the power or authority to rule.

- Kāwanatanga: government, dominion, rule, authority, governorship and province.

The English version guaranteed ‘undisturbed possession’ of all properties, but the Māori version guaranteed ‘tino rangatiratanga’ (full authority) over ‘taonga’ (treasures, which can be intangible). - Tino rangatiratanga: chieftainship; full, exclusive and undisturbed possession.

Today, the Treaty represents so much more, emphasising equity, education and preservation of Māori culture and Tikanga. - Tikanga: a Māori concept with a wide range of meanings–culture, custom, ethic, etiquette, fashion, formality, lore, manner, meaning, mechanism, method, protocol and style.

Click here to read the text of the two versions (including a translation in English of what the Māori version says) on the Te Papa website.

Here is a summary of the articles of Te Tiriti in the Māori and English versions:

| Article | Maori version | English version |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | This article gave Queen Victoria governance (kawanatanga) over the land. The word ‘kawanatanga’ came from the transliteration of the English word ‘governor’. Before Te Tiriti, ‘Kawana’ had been used in te reo Māori to refer to the governor of New South Wales (who was under the Queen) and to Pontius Pilate in the Bible (who was under Caesar). People at the time would not have understood it as meaning sovereignty or having complete power over New Zealand. | This article gave Queen Victoria sovereignty over New Zealand. This was a much stronger right than Kawanatanga or governance, which many Māori interpreted as setting up a government to control the Pākehā settlers. |

| 2 | This article stated that the chiefs would retain their full chieftainship rights (te tino rangatiratanga) over their lands, villages and all other treasures. Article 2 also said that the Crown could buy land, if Māori wished to sell it. |

This article guaranteed the chiefs full, exclusive and undisturbed possession over their lands, estates, forests, fisheries and all other properties. This was not as strong as having 'full chieftainship rights' and was limited to property, whereas 'treasure' had a wider meaning. This article also said that the Queen had pre-emption rights when purchasing land Māori wished to sell, which meant that Māori could sell only to the Crown. |

| 3 | This article guaranteed Māori the same rights as British citizens. | Article 3 is considered to have a very similar meaning in English. |

| 4 | Article 4 was a discussion between the Catholic Bishop Pompallier and the Anglican missionary William Colenso in relation to religious freedom in New Zealand. William Hobson, the governor, agreed to protect 'several faiths (beliefs) of England, of the Wesleyans, of Rome and also of Māori custom (Tikanga Māori)'. This article guaranteed religious freedom for all in the new nation, including Māori. | As this article was an oral discussion, the English version of the Treaty did not include it. |

It is common now to refer to the intention, spirit or principles of the Treaty.

The formation of the Waitangi Tribunal led to discussions with the government and the courts that sought to ‘thrash out’ the principles of Te Tiriti o Waitangi. As summarised in Te Ara: 'The treaty is deemed to bind Māori and Pākehā New Zealanders in a partnership in which they must act reasonably and with utmost good faith', and the principles are one way in which this is articulated.5

The first time these principles were used was in the Act of Parliament that formed the Waitangi Tribunal. Since that time there have been other official references to treaty principles. Because these principles have been defined through court cases, new laws, Waitangi Tribunal findings and a 1989 government statement, there is no final or complete list of Treaty principles.

However, it is agreed that these principles are included:

The Treaty set up a partnership, and the partners have a duty to act reasonably and in good faith.

- The Crown has the freedom to govern.

- The Crown has a duty to actively protect Māori interests.

- The Crown has a duty to remedy past breaches.

- Māori retain rangatiratanga over their resources and taonga and have all the rights and privileges of citizenship.

- The Crown has a duty to consult with Māori.

- The needs of both Māori and the wider community must be met, which will require compromise.

- The Crown cannot avoid its obligations under the Treaty by giving authority to some other agency.

- The Treaty can be adapted to meet new circumstances.

- Tino rangatiratanga includes the management of resources and other taonga according to Māori culture.

- Taonga include all valued resources and intangible cultural assets.

For many years, and even nowadays, many social services and health organisations (including government agents) have used the ‘3Ps’ framework to incorporate treaty-based ideas and practice into the work they do.

This well-established Crown Treaty framework came out of the 1986 Royal Commission on Social Policy. The three principles are Partnership, Participation and Protection. Does this sound familiar to you?

Partnership

Acknowledges sovereignty/governance and working together with the same rights and benefits as subjects of the Crown. This principle is about equality and equity between Maori and all other New Zealanders. It is working together at all levels of an organisation and having a say in the policy and management of organisations. It means engaging with Māori in the community when you plan work that affects them.

Protection

Acknowledges the protection of rights, benefits and possessions. As well as ensuring equal rights and protecting possessions, it means that Māori tikanga (culture and protocols) and taonga (treasures) such as Te Reo Māori (Māori language) are respected and given equal footing to the tikanga and taonga of other cultures.

Participation

Acknowledges sovereignty and governance. Participation means ensuring equal participation at all levels and that Māori have input into decision-making directly affecting them.

These principles, though widely used, are now regarded as outdated, and it is accepted that they are a ‘reductionist view’ of Te Tiriti.6

The fourth Labour government became the first government to set out a set of principles to guide it on matters relating to Te Tiriti in 1989. No later government has defined any new principles since.

The principles are:

- The Kawanatanga Principle: The government has a right to govern and make laws.

- The Rangatiratanga Principle: Iwi have the right to organize as iwi, and under the law, to control their own resources.

- The Principle of Equality: All New Zealanders are equal before the law.

- The Principle of Reasonable Cooperation: Both the government and iwi are obliged to accord each other reasonable cooperation on major issues of common concern.

- The Principle of Redress: The government is responsible for providing effective processes for the resolution of grievances in the expectation that reconciliation can occur.

The 2019 Waitangi Tribunal Report ‘Hauora: Report on Stage One of the Health Services and Outcomes Kaupapa Inquiry’ has recommended a set of principles to provide a new framework for how government health and disability organisations (and consequently non-governmental organisations) can meet their obligations under Te Tiriti, not only in planning but in their day-to-day operations. These principles are also being adopted in social services, including youth work.

The principles applicable to health and disability services are as follows7:

Tino RANGATIRATANGA

The guarantee of tino rangatiratanga provides for Māori self-determination and mana motuhake (special powers) in the design, delivery and monitoring of services.

Equity

The principle of equity requires the Crown to commit to achieving equitable outcomes for Māori.

Active protection

The principle of active protection requires the Crown to act, to the fullest extent practicable, to achieve equitable outcomes for Māori. This includes ensuring that it, its agents, and its Treaty partner are well informed on the extent, and nature, of both Māori outcomes and efforts to achieve equity for Māori.

Partnership

The principle of partnership requires the Crown and Māori to work in partnership in the governance, design, delivery, and monitoring of services. Māori must be co-designers, with the Crown, of systems for Māori.

Options

The principle of options requires the Crown to provide for and properly resource kaupapa Māori services. Furthermore, the Crown is obliged to ensure that all services are provided in a culturally appropriate way that recognises and supports the expression of Māori models of care and practice.

How does this affect marketing?

As a future employee in a digital media, design and/or marketing role in Aotearoa New Zealand, you have a responsibility to uphold these principles in your work.

For example, when developing a piece of work, you have a responsibility to ensure that you create meaningful partnerships with the Māori community. This partnership upholds the treaty and maintains respectful designs and campaigns. Anything with cultural reference must be co-designed with the impacting community.

Awareness of cultural appropriation has become more widespread in recent years. As the spread of information and knowledge on the subject increases, the negative impact of the process is more evident than ever.

What is cultural appropriation?

'Appropriation' refers to the act of adopting or using an element or elements of another culture. It is selective and involves the picking and choosing of elements primarily for their aesthetic value without understanding the value they have and their context within the culture they are from.

Culture

Culture can be defined as 'the ideas, customs and social behaviours of a particular people or society'. It is worth noting that culture is not defined along geographical or racial lines. It applies to groups of people.

Elements of culture

When discussing culture in sociological terms, we often refer to the 'element(s) of culture'. These elements help us understand more about the context of cultural elements being appropriated.

Symbols

Symbols can be a form of nonverbal communication. They can be placeholders that are intended to represent something else and to evoke emotion by association.

Religions often have a wide variety of symbols that have specific meanings. For example, the crucifix and the Star of David. Other cultural symbols include the yin and yang symbols.

Symbols do not have to be physical or written. The act of shaking hands in many cultures is a symbol of politeness in greetings. Holding hands can show a loved one (and the people around you) your feelings. Giving a 'thumbs up' is another example of a cultural symbol.

Not all cultural symbols have positive effects on communities. The MAGA hat and the BLM t-shirt are examples of cultural symbols that elicit negative responses from those on the other side of their aligned cultures.

Language

Languages, both written and spoken, are some of the most significant ways culture is shared and passed on. A shared language is essential to the development and evolution of a culture.

Language does not have to mean the dominant language spoken in a particular country (English, Māori, French etc.). It can also refer to the colloquialisms found within a culture; for example, the culture of car enthusiasts has words and phrases that might seem foreign to people outside of the culture.

Norms

Norms are the standards and expectations of behaviour. It is how people within a culture expect others to behave in different situations.

These expectations can be formal, like laws and codes that are enforced, or informal customs and standards that, while still considered important, are not enforced.

An interesting cultural norm amongst Wellington public transport users is the practice of thanking the bus driver. At each stop on a bus route, the phrase 'Thanks, driver' can be heard multiple times from exiting passengers.

In many western cultures, eye contact while speaking is considered an act of respect; while in some Pacific cultures, direct eye contact can be regarded as disrespectful.

Values

Every culture has values. They help members judge what is right or wrong, good or bad, desirable or undesirable. The values help to shape the norms.

In many western cultures, individualism is highly valued. 'Become independent', 'standing on your own two feet', 'looking out for number one' are examples of phrases that might have a positive meaning in these cultures.

Other cultures value the group, the community and the family higher than the individual. You might see extended families living together, younger members taking more responsibility for their siblings, and multi-generational households.

Attitudes towards work, education and the environment are all influenced by cultural values.

Artefacts

Artefacts are physical objects that have significance to a culture. We often think about artefacts in relation to ancient civilisations. We imagine archaeologists digging them out of the ground in places like Egypt.

All cultures have artefacts. The carvings that adorn a Maere (meeting house), or the greenstone taonga gifted to Iwi/tribe members, are examples of artefacts.

If you talk to people involved in car cultures, you may recognise some of their artefacts: turbochargers, spoilers, 10mm sockets.

Examples of cultural appropriation

Over the years, there have been many examples of cultural appropriation. The examples are often highlighted by an imbalance of power and a lack of respect for the victimised culture.

In December 2019, Princess Cruises issued an apology after members of the crew from one of its ships visiting Tauranga dressed in grass skirts and danced with black markings drawn on their faces while ushering passengers on and off the ship ('Cruise company apologises after staff pose as Māori for traditional welcome', 2019).

These crew members had appropriated elements of Māori culture. The use of traditional dress and performing dance without consultation with local iwi was condemned as culturally insensitive.

Ta moko–traditional Māori tattooing, often on the face–is a taonga (treasure) to Māori for which the purpose and applications are sacred (Ta moko - the significance of Māori tattoos, n.d.). Applying facial markings to mimic traditional ta Moko is an example of cultural appropriation.

Blackface? This one is pretty obvious. Don’t do it! Blackface became popular in the US after the Civil War as white performers played characters that demeaned and dehumanised African Americans.

In recent years, many prominent political leaders, actors, and entertainers have come under fire for their use of blackface while attending public and private events in their past.

Blackface is a very overt form of cultural appropriation. More subtle forms of similar types of appropriation might include using a model of different ethnicity from the one portrayed or emphasising a cultural stereotype to make a point in an ad.

Lingerie brand Victoria's Secret has been accused of and apologised for cultural appropriation on several occasions--most famously in 2012 when model Karlie Kloss wore a feather headdress that was clearly appropriated from Native American culture. The suede fringe, turquoise jewellery and leopard-print accents all highlighted a link to Thanksgiving. The outfit was perceived to glamorise the genocide Indigenous people experienced at the hands of European settlers and American colonists (Anderson, 2020).

Never trivialise sacred artefacts or symbols. Using artefacts and symbols in ways that do not honour or respect them to the same extent that would be expected within their own culture is another sign of cultural appropriation.

In 2016, an Auckland brewery used images depicting the 'sacred' ancestors of Te Arawa (the leading tribal group of Rotorua and surrounding areas) on their beer bottles.

Rotorua kaumatua (elder) Paraone Pirika described the representations of his ancestors as culturally insensitive and severely misrepresentative. The association with alcohol was also not appreciated (King, 2016).

'My tipuna knew nothing about alcohol and the effects of alcohol when they were alive, many moons ago' - Paraone Pirika

In 2018, a Belgium beer brewery labelled one of its beers 'Māori Tears'. Māori rights advocate Karaitiana Taiuru said the beer was another classic example of a brewery that is causing offence and 'The idea of drinking someone else's tears is spiritually offensive to a traditional Māori worldview' (Fitzgerald, 2018).

In 2020, a Canadian brewery and a New Zealand leather store made similar blunders by misusing the Māori word 'huruhuru' which can be translated to mean feathers or fur; however, it is more commonly used in reference to pubic hair (Anderson, 2020).

Avoiding cultural appropriation

The best way to avoid cultural appropriation is to engage meaningfully and authentically with the culture you are borrowing from.

Take the time to learn about and truly appreciate a culture before you borrow or adapt elements of that culture. Learn from those who are members of the culture, visit venues run by members of a culture (marae), and attend authentic events (powhiri, tangi, kapa haka) (Cuncic, 2020).

Ask permission, give credit and recognise the origin of elements that you borrow from other cultures rather than claiming them to be original ideas. Allowing members of that culture to be co-creators of your design is the best way to ensure respect is given.

Watch the video, 'Here’s what it looks like when cultural appropriation is done right'.

Cultural marketing

What is cultural marketing?

Cultural marketing is a type of marketing that targets a specific group of potential clients that share a common culture or demographic. The audience/customers are of a specific ethnicity, and cultural marketing uses the ethnic group's various cultural referents such as tradition, language, religion, and so on to interact with and persuade them. Let us look at what cultural values drive a society.

Cultural values of a society

What is acceptable and undesirable behaviour is influenced by a society's values.

Values can be applied to a whole country in some cases. The US, for example, is widely seen as a very individualistic society, with residents making purchase decisions based on personal tastes. Other nations, for instance, Japan, tend to focus purchasing decisions on the well-being of a group, such as the family. However, cultural values differ from country to country. Urban citizens of the US have pretty different marketing methods than rural residents in New Zealand. These cultural distinctions should be reflected in marketing to these various demographics.

Why use cultural marketing?

People have cultural borders, and their beliefs and customs influence their thoughts and decisions to some extent.

Because marketers are aware of this, they incorporate cultural norms and standards into advertisements in a way that buyers can relate to the characters in the advertising and hence feel a sense of affinity for the brand. It has a favourable impact on marketing because it generates more areas of interest in less time. Companies must use cross-cultural marketing to target customers who are culturally different from them.

So, what does cross-cultural marketing imply?

'Cross-cultural marketing' refers to the strategic process of marketing to customers from cultures other than the marketer's own. Social conventions, values, language, education, religion, economic systems, business etiquette, laws and way of life are examples of essential cultural characteristics to examine. Typically, cross-cultural marketing uses the differences in cultural norms among ethnic groups to interact with and persuade that audience.

Understand cultural norms

You want to avoid cultural mistakes that could damage your brand. People are influenced by where they come from. Some cultures are conservative while others are not. An advertisement watched in the US, on the other hand, should not depict business associates kissing on the cheek, while this may be acceptable to a Paris audience. Knowing where someone comes from and what matters to them is critical in learning how to communicate with them. At the end of the day, excellent marketing is nothing more than the start of a dialogue. Building your customer profiles is a great place to start if you aren’t sure who your customers are.

In New Zealand, it is critical to recognise that, regardless of your level of familiarity with Maori culture, it is vital to spend time investigating the cultural value of your planned branding and intellectual property. It can be difficult to know who to consult with or to identify who has the authority to grant permission on a Māori element. There is no general rule. If engaging the services of a professional is not an option, the following are suggestions.

If your product or brand uses a Māori element that is specific to a geographical area, you should discuss the element with the local Māori group. Each geographical area of New Zealand is within the boundary of an Iwi, marae or hapū. Appendix I has the Takoa resource which is a comprehensive listing of Māori organisations, services and businesses. Other avenues could include the Internet or your local MP’s office for more information. If using a Māori cultural element, it is essential that you create a cultural narrative around your brand or product including the usage, you’re thinking and where you gained inspiration from. In Māori culture, this is called ‘whakapapa’. Everything in the Māori world has whakapapa. It is also your first line of defence if someone accuses you of cultural appropriation.

In most instances, recognising a Māori cultural element is the first step. There have been many examples in the media where the user has not recognised that a word, story, image, picture, etc. forms part of Māori culture.

A widely published example is a New Zealand brewery selecting the names HINEMOA and TUTANEKAI as brand names for a range of beers. These names were selected because they were the names of streets in the area where the brewery was based. However, the origins of these names were not researched. And if a little research had been done, then the New Zealand brewery would have found that these names are in fact the names of two well-known Māori ancestors from a hapū (clan or descent group) based on the shores of Lake Rotorua. Once the brand was put on the market, the hapū objected to the use of their ancestors’ names in association with alcohol.

If some research had been done, and the New Zealand brewery would have recognised that a significant Māori element existed in those names, then steps may have been taken to avoid the disrespect and humiliation caused.

(Strategy, Experience and BasuMallick, 2021)

Finding the correct balance between global brand platforms and cultural settings has always been a challenge for global marketers. The digital technology revolution, the growing marketplace complexity within countries around the world, and the increasing importance of getting local relevance right given the re-energisation of cultural norms movements around the world are all driving this important business practice into a new phase.

Watch the following videos and answer the questions that follow.

- Identify the different cultures portrayed in this video.

- Comment on the cultural appropriateness of this video.

Share your answers with your peers in the forum posts.