In this topic, we focus on the elderly in relation to safe and effective exercise design and delivery. You will learn:

- Who are the elderly?

- Age related physiological changes

- Physical activity benefits and guidelines

- Programming consideration.

Terminology and vocabulary reference guide

As an allied health professional, you need to be familiar with terms associated with basic exercise principles and use the terms correctly (and confidently) with clients, your colleagues, and other allied health professionals. You will be introduced to many terms and definitions. Add any unfamiliar terms to your own vocabulary reference guide.

Activities

There are activities throughout the topic and an end of the topic automated quiz. These are not part of your assessment but will provide practical experience that will help you in your work and help you prepare for your formal assessment

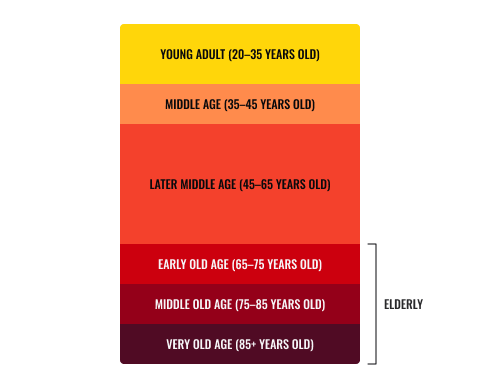

When discussing individuals in relation to their age, they will fall into one of the categories outlined below.

Traditionally, the term “elderly” refers to individual who are 65 years or over.

Within individuals 65 years and older, as a result of the onset of aging, physiological differences have been identified. These are of importance to be aware of and ensure you consider when planning safe and effective training programs.

Early old age - 65-75 years

Typically, a modest increase is seen in activity in order to fill days, however, a decline in mobility occurs along with impaired physical capacity. There is also the development of significant changes in posture and some disability.

Middle old age - 75-85 years

Often, individuals within the ages of 75-85 years old have one of more physical disabilities with the process of total dependence beginning.

- 10 yrs of partial disability

- 1 yr total dependence

- Loss of independence

New Zealand’s elderly population

As in every country of the world, New Zealand has a booming aging population! The NZ Ministry of Heath reports that New Zealanders are not only living longer, but the older population is becoming more ethnically diverse and growing at a faster rate than the younger New Zealand population. The following reflects the predicted growing rate of the elderly based on the 2016 statistics.

Age 65+

- At the end of 2016, 711,200 people were aged 65-plus

- Those aged 65 years and older will roughly double, from 711,200 in 2016 to between 1.3 and 1.5 million in 2046 (30 years)

Age 80+

- At the end of 2016, 169,000 people were aged 80+

- That number is projected to climb to 392,800 by 2036 (20 years), an increase of 132.4%!

Age 90+

- At the end of 2016, 5,800 people were aged 95-plus

- By 2036, it's projected the number will rise to 14,500. An increase of 150 per cent (20 years)

- By 2056, the number will climb to 42,400 aged 95-plus. That's a 631% increase from 2016.

There is a significant increase in numbers of elderly individuals with growing risk factors towards health conditions and decreased daily physical capacity. Physiological changes occur within each organ and body system as aging occurs. Let us take a closer look at some of the changes which occur as a result of aging.

Metabolism

Metabolism is the term given to the sum of all the chemical processes within the body required for optimal survival and maintenance of life. The speed of metabolism determines how many calories are burned per day, the faster the metabolism, the great the number of calories utilised. The greatest contributor to metabolism is the basal metabolic rate (BMR) which refers to the amount of energy burned in order to function while at rest.

As aging occurs, it has been noted that the rate of metabolism decreases 10% from young middle age until retirement. It does so due to a few factors which play a part in influencing the speed of metabolism. Examples of age-related factors which impact BMR and metabolism would be:

- Muscle mass: muscle requires more energy to perform its function, therefore, the greater the lean muscle mass, the greater the energy burn/calorie expenditure (including energy burnt at rest).

- Age: typically, metabolic rate declines with age due to a reduction of muscle tissue and changes to physiological aspects such as neuroglial and hormonal processes.

- Gender: Males typically have faster metabolism than females.

- Physical activity levels: exercises increases lean muscle mass and requires input from the body’s energy systems therefor burning more fuel and at a faster rate.

- Diet: what and when food is eaten will play and influential role on BMR

- Drugs and medications: nicotine and caffeine can increase BMR while certain medications such as steroids as well as other medications can result in an individual’s weight gain, despite their diet.

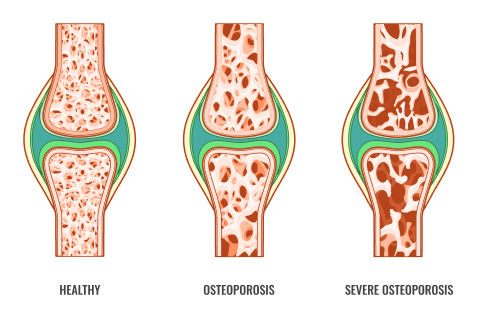

Bone mineral density decreases with age, beginning from the approximate age of 50 years old. This decrease in bone density, the structural integrity of bone occurs as there is a greater volume of bone break down (reabsorption) than bone formation. This increasing rate of bone breakdown leads to bone tissue being more “porous”, leading to the condition known as osteoporosis. Osteoporosis is a degenerative condition of bone tissue which providers greater risks for these individuals in performing activities for daily life (ADL) and puts them at greater risk of fractures, common fracture sites being hips, spine and wrists. These fractures occur easily and take longer to heal. Studies have shown women to be at a great risk of developing osteoporosis and loosing approximately 8% of bone tissue per year with males loosing approximately 3%.

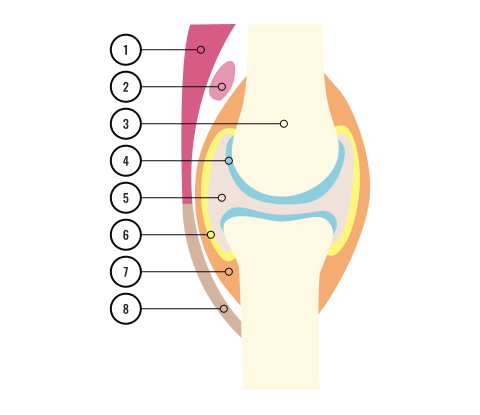

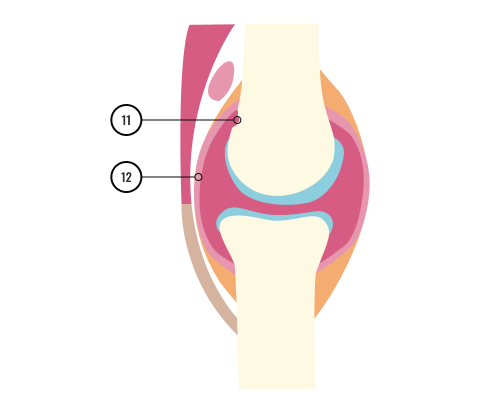

Degenerative joint diseases

- Muscle

- Bursa

- Bone

- Cartilage

- Synovial fluid

- Synovial membrane

- Joint capsule

- Tendon

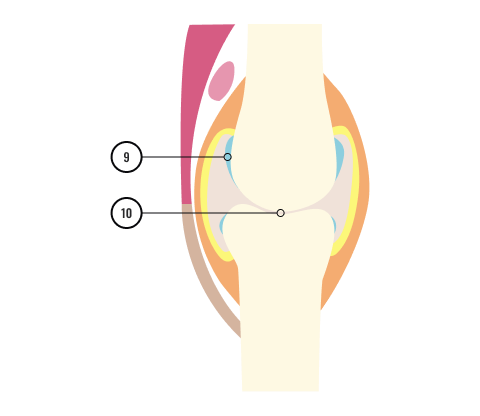

- Eroded cartilage

- Bone ends rub together

- Bone erosion

- Swollen, inflamed synovial membrane

Joint degeneration or degenerative joint disease (DJD) refers to osteoarthritis and is more commonly referred to as ‘wear and tear’ arthritis as it occurs as a result of the wearing down of the protective connective tissue (cartilage) which covers the end of each bone. This tissue serves to protect the bones and prevent them from rubbing together when the body is moving. Over time, this tissue wears down and bones begin to rub together which can cause pain, swollen joints, and joint stiffness.

Osteoarthritis is the most prevalent form of arthritis with around 386,00 New Zealand adults living with the condition in 2018, approximately 10% of the population!

Mobility

This is a hugely important goal when working with elderly clients! The elderly experience a decreased range of motion through the joints which occurs due to deterioration and loss of function throughout the surrounding tissues, impacting activities for daily life (ADL). Typically, these difficulties begin to appear around the ages of 60-65 years old approximately with it being recorded that 35% of those over 85 years of ages have associated problems when it comes to ADL such as:

- walking

- showering

- dressing

- household chores

- transferring from a chair to walking (performing sitting to standing motions)

- getting into or up from a seated or lying position.

These degenerative changes in the body, as well as impacting the ability to perform every day activities can also lead to dizzy spells ( the feeling of a headrush), typically induced due to postural hypotension, particularly those which require spatial movements such as transitioning from laying or sitting to standing and vice versa.

Falls

Falls, seen more in females than males, are one of the leading causes of fatalities in those 70 years and above with 25% of the aged population experiencing one serious fall per year. Falls typically arise from factors such as degenerative tissues around joints however there are other factors which impact the fall rates within the elderly, such as:

- neurological and musculoskeletal impairment

- visual impairment

- psychological

- medication

- postural hypotension (head rush)

Aerobic capacity

From the age of 20 years old, VO2max and cardiovascular endurance begin their decline. Knowing that maximal training heart rate is calculated in relation to age (maximum heart rate= 220-age), we can also be aware that there will be a reduction in maximal heart rate as individuals age.

Additional factors which contribute towards a decline in aerobic capacity in the elderly include:

- Reduction in myocardial contractility (the ability of the heart muscle to contract) leads to decrease in stroke volume (the volume of blood pumped from the left ventricle per beat)

- Arteries are approximately 30% obstructed by the age of 45

- Decrease in elasticity of the of major blood vessels

- 50% decrease in max lung capacity (30-70yrs).

Other physiological age related changed

Additional age-related changes have been identified within the elderly population which are also pertinent to be aware of, particularly when screening clients, as well as during the stages of program design, for example:

- Blood pressure: resting blood pressure and blood pressure recorded whilst exercising increases with age.

- Body composition: the elderly will typically exhibit a decrease in fat free mass (lean body mass) and an increase in percentage of total body fat

Physical activity is key within the lifestyle of every individual, regardless of age. However, it is vitally important within the elderly population in order to delay or decrease the physiological changes which occur in relation to aging. New Zealand Ministry of Health makes the following recommendations in their Guidelines on Physical Activity for Older People (aged 65 years and over):

For all older people in New Zealand

- Be as physically active as possible, limiting sedentary behaviour

- Consult an allied health professional before beginning or increasing physical activity

- Start off slowly and gently, gradually increasing to recommended levels

Aim to achieve the following levels of activity (selecting one option for aerobic activity):

- Aim to take part in aerobic activity on five days per week for:

- 30 minutes per day if activity is of a moderate intensity

- 15 minutes per day if activity is of vigorous intensity

- Session should be at least 10 minutes in duration at a time

- Aim to also perform three sessions of balance and flexibility activities and two muscle strengthening activities per week.

Recommendations for additional health benefits

For additional health benefits, older adults should work towards achieving the following:

- 60 minutes of moderate-intensity aerobic activity, five days per week

- 30 minutes of vigorous-intensity aerobic activity, five days per week

- An equivalent amount of combined moderate and vigorous-intensity activity per week.

Move it in order to not lose it! Should physical activities remain below recommended levels, this can result in a significant decline in postural strength, balance, mobility, and functional capacity along with an increased risk of disease states, injury and early fatality.

Recommendations for older adults who are frail

- Be as physically active as possible, limiting sedentary behaviour

- Consult an allied health professional before beginning or increasing physical activity

- Start off slowly and gently, gradually increasing to recommended levels

- Consult an allied health professional before beginning or increasing physical activity

- Aim to have a mixture of low impact aerobic activity, along with activities to enhance resistance, balance, and flexibility

- Consult with their General Practitioner or allied health professional regarding the benefit of Vitamin D tablets.

Benefits of physical activity

Both aerobic and resistance activity hold an array of benefits for older adults which can positively impact quality of life and activities for daily living.

Aerobic activity can improve or maintain VO2max through strengthening the lung and the chest muscles, improving, or maintaining lung capacity. Appropriate aerobic activity will also ensure the heart is exposed to regular increased demands, strengthening the myocardium through appropriate aerobic intensity and in turn, slowing the age-related increase of blood pressure.

Resistance training, both in relation to physical activity, or a regular exercise regime, holds several significant benefits in relation to prolonging both quality and length of life via tackling the physiological effects of aging, with the key difference between both being the onset and adherence of these benefits. Vital benefits to support age-related physiological benefits in the elderly are as follows:

- Body mass maintenance: the inclusion of resistance training supports combating the age-related increase in total body fat and decrease in lean muscle mass in order to an optimum body mass within the elderly population.

- Muscle hypertrophy: as we age, we begin to experience sarcopenia (age and inactivity related loss of muscle mass and strength). Implementing appropriately prescribed resistance training acts to reduce the progression of sarcopenia and aids in maintaining quality of life, mobility and independence, activities for daily living and a decreased risk of injury.

- Disease prevention or control: it has been suggested through research that resistance training has positive benefits on the immune system. This can result in the prevention and possible reversal of certain chronic conditions. All programs should be designed in collaboration with an individual’s allied health professional(s).

- Mental health: effective physical activity can result in an improvement of an individual’s mental health. Mental health benefits are acquired when mixing with other individuals, feeling more capable in certain activities, regaining, or reducing the loss of independence, as well as other benefits that will have an overall boost in their self-confidence.

- Improved resting metabolic rate: As resistance training is effective at increasing lean muscle mass and muscle burns more calories than other tissue types at rest, it is therefore said that regular, effective resistance training will increase the basal metabolic rate (calories burned while resting). This could also aid to widen food choices whilst looking after body mass and body composition.

Prior to implementing a training program for an elderly client, there are a few important guidelines and considerations for this special population to ensure they are receiving a safe and effective exercise program.

Adequate medical screening: this is a vital first step in the process for both programming and safety. This session should be conducted thoroughly and respectfully. The aim of this session is to determine risk factors and or disease limitations prior to embarking on an exercise routine. This is to ensure the safety of the clients during exercise testing and to effectively contribute towards as suitable, sustainable, and safe exercise program.

Pre-screening is a two way process, in the sense that, this stage should be used to determine not only if your client is a suitable candidate for exercise but also if the needs of your client falls within your scope of practice, i.e. are you qualified to safely guide them through their exercise needs? If not, do not be a hero, ask for further advice from your gym manager, a more experience personal trainer or refer to an allied health professional such as a G.P or Exercise Physiologist for a more medically comprehensive screening and exercise supervision.

All health and fitness professionals conduct a pre-screening session to:

- optimise safety

- develop sound and effective exercise prescription

- identify any existing musculoskeletal conditions

- determine current health and nutritional status

- identify individuals with disease symptoms and risk factors for disease development who should receive medical clearance before starting an exercise program

- identify and exclude individuals with medical contra-indications to exercise

- identify individuals with other special needs.

Appropriate exercise selection- it is important to ensure an appropriate selection and intensity of exercise when considering both the safety and the goals of the client. Should an exercise seem to easy and not presenting sufficient challenges within safe parameters, progress the exercise to challenge the client. Conversely, should the selected exercise be too challenging or demanding for the client, regress the exercise to one which promotes safer, more stabilising movements, progression can be achieved if and when the client is capable of performing the movement both safely and correctly.

Appropriate level of supervision: it is of the upmost important that the client is supervised at all times to ensure each exercise is performed safely and correctly and within an appropriate intensity level (RPE). Appropriate supervision will aid in ensuring a reduction or complete avoidance in any aggravation of age-related risk factors for instance a cardiovascular or cerebrovascular incident or, muscle or joint conditions such as rheumatoid arthritis or osteoarthritis.

Client consideration: when training elderly clients, it is important to be aware that they may have barriers to effective communication such as loss of hearing, vision, balance and co-ordination and a loss in confidence. Furthermore, due to their age and potential medical conditions, they may also have perceptual deficits (difficulties or differences in inputting, processing and recalling information) such as ADHA, Alzheimer’s and dementia for example. This would require you to adapt certain aspects of your delivery and instruction such as language concise sentences will be more appropriate at times) demonstration of exercise and safety of technique.

Programming design and implementation guidelines

When working with an elderly client, additional to their personal and health related goals, a major goal is to develop muscular fitness to enhance an individual’s ability to live a physically independent lifestyle. This brings confidence, longevity, and vitality as well as much more.

The first several resistance training sessions of each new program should be closely supervised and monitored by trained personnel who are sensitive to the needs of the elderly. Typically, the first eight weeks, should begin with minimal resistance to allow for adaptations of the connective tissue elements. During the program, it is of upmost important that participants maintain normal breathing throughout (there can be a tendency to hold the breath) and that proper technique is both taught and used during each session.

Let us now consider some of the finer elements involved in program design when working with elderly patients:

- Progressive overload: Overload initially by increasing the number of repetitions, and then by increasing the resistance.

- Reps: Never use a resistance that is so heavy that an exerciser cannot perform at least eight repetitions

- Speed: Stress that all exercises should be performed in a manner in which speed is controlled (i.e. stay away from ballistic movements)

- Pain free: Perform the exercises in a range of motion that is within a “painfree arc” ( implying the maximum range of motion does not hurt or is uncomfortable)

- Frequency: 30 minutes of gentle activity, as many as 7 times per week

- Compound: Perform multi-joint exercises as opposed to single joint exercises

- Machinery: Given a choice use machine to resistance train, as opposed to free weights (poor balance and coordination). Machines require less skill to use, permit the user to only move and perform the exercise in a pre-determined movement pattern, protect the back by stabilising the users body position, and allow the user to start with lower resistances

- Type: Two strength and resistance training sessions per week are the minimum number required to produce positive physiological adaptations. Interval training is great because of the lower intensity bouts for recovery, cardio work should start at 50% intensity of HR max and increase from there. Exercise should be fun and simple to perform with a focus on skill development rather than body image and looks.

- Functional: Consider postural and exercises that help with ADL (activities of daily living)

- Stretching: Ease into stretches gentle, never performed with bouncing during a stretch, remind mind the client to breathe during their stretches, and think about their pain free range of motion (ROM).

Important note for arthritic patients - never permit arthritic patients to participate in strength training exercises during active periods of pain or inflammation

In this topic, we focused on the elderly in relation to safe and effective exercise design and delivery. You learnt:

- Who are the elderly?

- Age related physiological changes

- Physical activity benefits and guidelines

- Programming consideration.