In this section, you will learn about the following:

- The key concepts of acceptance and commitment therapy.

- The key techniques and processes of acceptance and commitment therapy.

- The role of the counsellor and client in acceptance and commitment therapy.

Supplementary materials relevant to this section:

- Reading A: Acceptance and Commitment Therapy

- Reading B: ACT in a Nutshell Metaphor

- Reading C: Acceptance of Emotions

- Reading D: Core Competencies of the ACT Therapeutic Stance

- Reading E: Embracing Your Demons

This module will teach you more about acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT). It is important to note that the theoretical concepts, processes, and skills presented in this module provide only a brief overview of the approach. If you would like to achieve mastery of acceptance and commitment therapy, you will need to seek out more in-depth knowledge through further reading, attendance at professional development courses, and supervised practice.

Reflect

As you progress through this module, reflect upon your comfort level with the core concepts, underpinning principles and techniques of acceptance and commitment therapy. Do they match your values and beliefs? Would you be comfortable working within the principles of this model? Are you willing to apply the techniques of acceptance and commitment therapy?

What is Acceptance Commitment Therapy?

An animation that introduces you to Acceptance Commitment Therapy (ACT).

Watch

Acceptance and commitment therapy, known as ACT (pronounced as the word ‘act’), is an approach to counselling that was originally developed in the early 1980s by Steven C. Hayes, but rose to prominence in the early 2000s through Hayes’ collaboration with Kelly G. Wilson, and Kirk Strosahl as well as through the work of Russ Harris.

ACT seeks to help clients transform their ‘relationship’ with difficult thoughts and emotions. One of the central concepts of ACT is that many of the issues that clients present with in counselling are caused by the avoidance of internal experiences (i.e., thoughts or feelings) that are distressing or uncomfortable. For example, people often find that the process of trying to suppress unwanted thoughts only makes these thoughts more powerful. ACT practitioners do not seek to eliminate or change a client’s thoughts or emotions but instead seek to help the client view these thoughts and emotions for what they are – pieces of language and transient psychological events, not external “truths”.

Unlike more traditional cognitive-behaviour therapy (CBT) approaches, ACT does not seek to change the form or frequency of people’s unwanted thoughts and emotions. Rather, the principle goal of ACT is to cultivate psychological flexibility, which refers to the ability to contact the present moment, and based on what the situation affords, to change or persist with behaviour in accordance with one’s personal values. To put it another way, ACT focuses on helping people to live more rewarding lives even in the presence of undesirable thoughts, emotions and sensations.

(Flaxman, Blackledge & Bond, 2011, p. vii)

ACT practitioners encourage clients to approach problematic thoughts and beliefs from a psychologically flexible, mindful, and open perspective to prevent these problematic thoughts from overwhelming the person or determining their actions (Lloyd & Bond, 2015). Known as a third-wave behavioural therapy, ACT practitioners use several mindfulness and acceptance-based strategies and cognitive behavioural techniques. Ultimately, ACT interventions tend to focus on two main overarching goals (Harris, 2019, p. 4):

- Help clients to clarify what’s truly important and meaningful to them (i.e., values) and use those to guide, inspire, and motivate clients to do things that will enrich and enhance their lives.

- Teach clients skills to handle difficult thoughts and feelings effectively, so they can fully engage in their actions and appreciate life’s fulfilling aspects.

In a nutshell, ACT gets its name from its core ideas of accepting what is outside of your personal control and committing to action that improves and enriches your life.

Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT)

The presenter in this video, takes you through the development history, theory that underpins ACT: relation frame theory (RFT), and practice of ACT.

Watch

Check your understanding of the content so far!

Read

Reading A - Acceptance and Commitment Therapy

Reading A introduces acceptance and commitment therapy, including its developments and basic concepts.

The ACT model suggests that a couple of core processes commonly contribute to emotional distress and psychological disorders: cognitive confusion and experiential avoidance.

Cognitive fusion

Cognitive fusion is a term used to refer to when an individual is allowing their thought processes (e.g., beliefs, assumptions, thoughts, attitudes, memories, or emotions) to have an excessive influence over their behaviour and awareness to the point that they are caught up in these and become disconnected from the present moment (Harris, 2019). Whilst these thoughts and emotions were never problematic, it becomes problematic when we become overly attached and ‘fused’ with them, believing that they reflect reality. When an individual is ‘fused’ with their thought processes, it can lead them to move away from the present moment and their true values. This often gives rise to experiential avoidance.

When we fuse with a cognition, it can seem like:

- Something we have to obey, give in to, or act upon;

- A threat we need to avoid or get rid of; or

- Something very important that requires all our attention.

(Harris, 2019, p. 22)

Cognitive Fusion and Defusion in ACT

This animation provides an example of why we get stuck to our thoughts and how we can reduce overthinking. Answer the questions that follow.

Watch

Experiential avoidance

Experiential avoidance is a term used to refer to the process of engaging in strategies to avoid certain private events, such as unpleasant or unwanted thoughts, feelings, emotions, urges, desires, memories, or bodily sensations (Harris, 2019). Common experiential avoidance strategies include avoidance, suppression, and distraction. Although these strategies seem effective in the short-term, they restrict an individual’s choices and, in the long-term, usually lead to a reinforcement of problematic thoughts, feelings, and sensations, leading to behaviours or decisions where a person must alter their life to avoid them.

The more time and energy we spend trying to avoid or get rid of unwanted private experiences, the more we’re likely to suffer psychologically in the long run. Anxiety disorders provide a good example. It’s not the presence of anxiety that creates an anxiety disorder. After all, anxiety is a normal human emotion that we all experience. At the core of any anxiety disorder lies excessive experiential avoidance: a life dominated by trying very hard to avoid or get rid of anxiety. For example, suppose I feel anxious in social situations, and in order to avoid those feelings of anxiety, I stop socializing. My anxiety gets deeper and more acute, and now I have “social phobia.” There’s an obvious short-term benefit of avoiding social situations – I get to avoid some anxious thoughts and feelings – but the long-term cost is huge: I become isolated, my life “gets smaller,” and I find myself stuck in a vicious cycle.

(Harris, 2019, p. 30)

The goal of ACT is, therefore, to help clients ‘defuse’ these internal processes and accept their private experiences through using strategies that increase their psychological flexibility.

Headstuck! What is Experiential Avoidance?

This short video explores the concept of experiential avoidance, and how it relates to the idea of career paralysis. Answer the questions that follow.

Watch

ACT Hexaflux

In his book ACT Made Simple, Russ Harris (2019, p. 8) explains psychological flexibility as “the ability to act mindfully, guided by our values”, which is thought to be facilitated through six core processes – these are often illustrated using the following ACT Hexaflex:

Increasing Psychological Flexibility

This video explores ACT and its powerful impact on psychological flexibility. Answer the questions that follow.

Watch

Six Core Processes of ACT

Whilst the six are being discussed as separate processes, they are considered as inseparable facets of psychological flexibility (Harris, 2019). As you will learn later, many ACT techniques are set out to promote more than one, if not all, these facets.

The six core processes of ACT aren’t separate. They’re like six facets of a diamond, and the diamond itself is psychological flexibility: the ability to act mindfully, guided by our values. [...]

Self-as-context (a.k.a the noticing self) and contacting the present moment both involve flexibly paying attention to and engaging in your here-and-now experience (in other words, “Be present”).

Defusion and acceptance are about separating from thoughts and feelings, seeing them for what they truly are, making room for them, and allowing them to come and go of their own accord (in other words, “Open up”).

Values and committed action involve initiating and sustaining life-enhancing action (in other words, “Do what matters”).

So we can describe psychological flexibility as the ability to “be present, open up, and do what matters.”

(Harris, 2019, pp. 8-9)

Reflect

Take a moment to think about your abilities to be psychologically flexible. Are there any areas that you have particular difficulty with? Are you fused with any certain thought processes? Are you able to be psychologically present? Are you committed to travelling in a valued direction?

The 6 Core Processes of ACT Explained | What They Mean and How to Use Them

This video explains the six Core Processes of ACT as the key in achieving psychological flexibility, where you are able to show up consciously to the present moment and facilitate positive behaviour change.

Watch

Check your understanding of the content so far!

Explaining ACT to Clients

Like other approaches you have learned, helping clients understand how ACT works and what it involves is essential for them to gain the full benefits of such an approach. According to Harris (2019, p. 55), a counsellor should at least cover the following points when obtaining a client’s consent to use this approach (using language tailored to suit each client and context):

- Clients play an ‘active’ role in the process. There are times when they will be encouraged to try new things or learn new skills – the client has a choice on whether to do them. However, it is a collaborative process between the counsellor and the client.

- The counsellor and client work together as a team to help the client build the sort of life they want to live.

- ACT involves the clients learning skills that enable them to ‘unhook’ themselves from difficult thoughts and feelings.

- ACT also involves clarifying the clients’ values and taking action to solve their problems, face challenges, and do things to make life better.

- Clients will likely leave each session with an action plan that enlists practical steps or strategies they will use in life.

- Clients will be asked to try new things out of their comfort zone (and clients can say no).

The following extract is an example transcript of how to introduce the ACT model to clients:

Note: “The wording ‘deal with your painful thoughts and feelings more effectively in such a way that they have much less impact and influence over you’ is important. ACT is not about trying to reduce, avoid, eliminate, or control these thoughts and feelings. It’s about reducing their impact and influence over behaviour in order to facilitate valued living.

(Harris, 2009, p.61)

Introducing the Client to ACT for OCD

This video specifically introduces the client with OCD to ACT.

Watch

Read

Reading B - ACT in a Nutshell

In this reading, you will find an exercise called “ACT in a Nutshell”, which encompasses metaphor and physical activity to help clients make sense of ACT and its essential concepts.

Generally, ACT practitioners use a wide range of exercises, worksheets, homework and metaphors as the central techniques to promote clients’ psychological flexibility. There is no particular order for which of these six core processes needs to be focused on first and which should follow – each can be fostered as a stand-alone intervention or in combination. In addition, the use of techniques in ACT is extremely flexible, with substantial allowances built in for creativity and adaptation. In fact, ACT practitioners are encouraged to create, adapt, and improvise activities for use with clients (Harris, 2019).

Here we will explore some of the most commonly used ACT techniques; however, as you continue reading, keep in mind that there are hundreds of exercises, metaphors, and other techniques that ACT practitioners use. If you wish to use the ACT

approach in your own work, you will need to spend some time developing your toolbox of techniques.

The Importance of Practice

When applying any ACT metaphors and techniques, it is important to ensure your delivery is smooth and adapted to the individual client. This requires a lot of practice. As you learn about the various ACT techniques, read them aloud as though you were using them with a client.

Techniques to Highlight the Costs and Ineffectiveness of Experiential Avoidance

Several ACT techniques can be used to help clients understand that their attempts to control their inner experiences are unworkable and even detrimental to them long-term. This is particularly useful for certain clients who are “excessively experientially avoidant, strongly attached to an agenda of emotional control: I must feel good; I must get rid of these unwanted thoughts and feelings” (Harris, 2019, p. 90). ACT practitioners often refer to this process as “Creative Hopelessness” (a term that isn’t used with clients) or “Confronting the Agenda”.

The goal is to get the client to examine the steps they have taken to control their thoughts/feelings, examine whether it has made things better or worse, and open up the possibility of using alternative methods to handle them (Harris, 2019). Clients who are motivated and open to change may not need as much work on this; however, it is not uncommon for counsellors to work on creative hopelessness across sessions with clients who are strongly attached to their need/desire to control their inner experiencing. Essentially, this group of techniques come down to exploring the following questions with the client (p. 93):

- What have you tried?

- How has it worked?

- What has it cost?

- What’s showing up?

- Are you open to something new?

How To Use The Choice Point in ACT

This video describes how to use the choice point is a tool used in ACT. Answer the questions that follow.

Watch

Join the DOTS

One technique that can be used when helping clients explore Question 1 is called ‘Join the DOTS’ - the counsellor asks the client to discuss the thoughts and feelings that are particularly problematic to them and everything that they have done to get rid of them, avoid, suppress, escape, or distract themselves from these thoughts/feelings (Harris, 2019). Counsellors can use the acronym ‘DOTS’ as a memory aid to assist in this process and prompt the client to think of how they use distraction, opting out, thinking, and substances/self-harm/other strategies to control their thoughts/feelings:

- D = Distraction. Have you ever tried distracting yourself from these feelings? What have you tried? Watching television? Listening to music? Getting out of the house? Getting busy? Playing computer games? Any other ways you’ve tried to distract yourself?

- O = Opting out: Have you ever tried opting out, withdrawing, or staying away from situations and people and activities that tend to trigger these uncomfortable thoughts and feelings? What kind of things have you quit or opted out of?

- T = Thinking strategies: How have you tried to think your pain away? Have you tried thinking of people who are worse off than you? Positive thinking? Challenging your thoughts or debating with yourself? Pushing the thoughts out of your head? Criticizing yourself? Telling yourself to just snap out of it or get on with it?

- S = Substances and other strategies: What kinds of substances have you tried putting into your body to get rid of pain? Drugs? Alcohol? Prescription medications? Are there any other strategies you ever use to try to escape these feelings? Have you seen doctors or therapists? Read self-help books? Tried things like exercise, yoga, meditation, diet change?

(Adapted from Harris, 2019, p. 94-95)

Once the client has identified their control strategies, the counsellor will encourage them to evaluate whether these strategies have worked in the long term (i.e., Question 2). For example, they may ask the client, “Did these strategies get rid of your painful thoughts and feelings in the long run so that they never came back? Or do your thoughts and feelings keep coming back?” In most cases, the client will identify that their control strategies have not worked – after all, they are in counselling seeking assistance. (If a client indicates a particular strategy is working for them in the long-term, it is still possible to invite them to explore the costs of these strategies when used excessively.)

From there, the counsellor will ask the client to consider what their control strategies have cost them (i.e., Question 3). The counsellor may prompt the client to think about its impacts on the various areas of their life. For example, the counsellor might ask, “How much time do you spend on distracting yourself?” or “How much time have you spent in your head, trying to think away your pain? How much did you miss out on?” (p. 97) It is also important to round off this discussion on a validating note, acknowledging the client’s hard work in using these strategies and they are not lazy or stupid.

Join the DOTS – Worksheet

Join the DOTS Worksheet

You can download a copy of Join the DOTS Worksheet from Russ Harris’ website. It is freely downloadable from the “Free Stuff” page, and contains what a practitioner could say when guiding a client through the steps in this exercise.

Attempted Solutions and their Long-Term Effect Worksheet

Another technique that can help with this process is asking clients to complete a homework exercise, such as the ‘Attempted Solutions and their Long-Term Effects’ Worksheet and then discuss it during the following session.

| ATTEMPTED SOLUTIONS AND THEIR LONG-TERM EFFECTS | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| What have you done to avoid or eliminate problematic thoughts, feelings, memories, emotions, or sensations? List everything you can think of, whether intentional or not. |

Did your thoughts and feelings go away? Did they return in the long run? Did they worsen? |

Has this brought you closer to a rich, full, and meaningful life? | What has this cost you regarding wasted time, energy, money, or negative effects on health, well-being, work, leisure, or relationships? |

This exploration often primes clients to identify the problem by using control strategies. However, some clients may need more help understanding that control is the problem, not the solution. Metaphors are a great way of making this point.

Metaphors

ACT practitioners often use different metaphors when working with clients. Two useful metaphors for highlighting the costs of experiential avoidance are the ‘Struggling in Quicksand’ metaphor and the ‘Tug-of-War with a Monster’ metaphor.

Struggling in Quicksand – Metaphor

The ‘Struggling in Quicksand’ metaphor helps highlight the damage that can be done by trying to control inner processes and is also useful as a way to begin introducing acceptance work with the client (Flaxman, Blackledge & Bond, 2011). An example of how a counsellor can apply this metaphor with a client is:

| Therapist: | "Remember those old movies where the bad guy falls into a pool of quicksand, and the more he struggles, the faster it sucks him under? In quicksand, the worst thing you can possibly do is struggle. The way to survive is to lie back, spread your arms and legs, and float on the surface. This is very tricky because every instinct in your body tells you to struggle, but if you do what comes naturally and instinctively, you’ll drown. And notice, lying back and floating is psychologically tricky – it doesn’t come naturally – but it’s a lot less physical effort than struggling." |

(Harris, 2019, p. 106)

Tug-of-War with a Monster – Metaphor

The ‘Tug-of-War with a Monster’ metaphor is used to help the client understand how difficult it is to do other things while they are struggling with something and the benefit that can be had by giving up the struggle (Flaxman et al., 2011). An example of how a counsellor can apply this metaphor with a client is:

| Therapist: | "Imagine that you are in a tug-of-war with some huge anxiety monster (Alter the name of the monster to suit the issue, for example, the depression monster.) You have one end of the rope, and the monster has the other. And in between you, there’s a huge bottomless pit. And you’re pulling backward as hard as possible, but the monster keeps pulling you closer to the pit. What’s the best thing to do in that situation?" |

| Client: | "Pull harder." |

| Therapist: | "Well, that’s what comes naturally, but the harder you pull, the harder the monster pulls. You’re stuck. What do you need to do?" |

| Client: | "Drop the rope?" |

| Therapist: | "That’s it. When you drop the rope, the monster’s still there, but now you’re no longer tied up in the struggle with it. Now you can do something more useful." |

(Harris, 2019, p. 106)

Examples of Metaphors

Watch the following two videos on examples of using Metaphors.

Watch

Watch

Thought Suppression – Exercise

Another technique often used to highlight the ineffectiveness of experiential avoidance – and bust the myth that we can control our thoughts and feelings - is a thought suppression exercise. Clients are asked to close their eyes and try hard not to think about a particular object, such as, “Don’t think about a blue elephant” (Hayes et al., 1999, cited in Harris, 2019). This exercise shows that attempting not to think about something does not eliminate that thought (Flaxman, Blackledge & Bond, 2011). Again, this helps clients open up to the possibility of accepting their thoughts and emotions rather than trying to control them.

Techniques to Teach Defusion Skills

Defusion and acceptance are two of the core therapeutic processes in ACT, but how exactly do counsellors assist clients in becoming defused and open up to their difficult inner experiences without needing to change or control them? Again, counsellors can use a wide range of additional metaphors, experiential exercises, worksheets and other techniques throughout the counselling process. We will explore a few of the most commonly used techniques.

Let’s start with defusion. The goal of defusion techniques is to help clients to (adapted from Harris, 2019, pp. 120-121):

- See the true nature of cognitions – they are nothing more or less than constructions of words and pictures.

- Respond to cognitions more flexibly – in terms of how helpful they are, rather than holding on to how true/false or positive/negative they are.

ACT practitioners use a simple technique to facilitate this process: treating the mind as an entity and thoughts as things that the mind is projecting (Harris, 2019). For example, ACT practitioners encourage their clients to use language such as “I’m having a thought that ____________” (e.g., saying “I’m having a thought that I’m not good enough”) rather than saying “I’m ___________ (e.g., “I’m not good enough”). Additionally, ACT practitioners may ask questions like “What does your mind tell you about that?” and refer to thoughts as stories. This type of language helps separate thoughts as external pieces of language, and ACT practitioners will likely get clients to do this repeatedly throughout sessions.

Another interesting technique to promote defusion is singing and silly voices to help defuse problematic thoughts. The basis of these techniques is to have the client concentrate on a negative self-judgement that they are having (e.g., “I am a loser”) for a brief period of time (e.g., 10 seconds). The counsellor will then instruct the client to take that phrase and either silently or aloud sing it to a tune (e.g., Happy Birthday) or repeat it in their head in a silly voice (Harris, 2019). By doing this repeatedly, the client will become distanced from the thought and see it as just a bunch of words in their head than a truth about who they are.

How to Detangle from Thoughts & Feelings

The Psychology Group discusses how to detangle from thoughts and feelings. Answer the questions that follow.

Watch

Techniques for Acceptance

Mindfulness techniques are also widely used during this part of the ACT therapeutic process. These techniques aim to help the client learn how to observe their thoughts with openness and curiosity and allow them to come and go rather than trying to control them. One commonly used technique is a popular mindfulness exercise named ‘Leaves on a Stream’.

Leaves on the Stream – Exercise

- Find a comfortable position, and either close your eyes or fix your eyes on a spot.

- Imagine you’re sitting by the side of a gently flowing stream, and there are leaves flowing past on the surface of the stream. Imagine it however you like— it’s your imagination. (Pause 10 seconds.)

- Now, for the next few minutes, notice each of your thoughts as it pops into your head … then place it onto a leaf, and allow it to come and stay and go in its own good time … Don’t try to make it float away, just notice what it does … It may float on by quickly, or it may go very slowly, or it may hang around … Do this regardless of whether the thoughts are positive or negative, pleasurable or painful … even if they’re the most wonderful thoughts, place them onto a leaf … and allow them to come and stay and go, in their own good time … they may float by quickly, or slowly, or they may hang around … simply notice what happens, without trying to alter it. (Pause 10 seconds)

- If your thoughts stop, just watch the stream. Sooner or later, your thoughts will start up again. (Pause 20 seconds)

- Allow the stream to flow at its own rate. Don’t speed it up. You’re not trying to wash the leaves away – you’re allowing them to come and go in their own good time. (Pause 20 seconds)

- If your mind says, “This is stupid” or “I can’t do it”, place those thoughts on a leaf. (Pause 20 seconds)

- If a leaf gets stuck, allow it to hang around. Don’t force it to float away. (Pause 20 seconds)

- (An optional add-in: introducing acceptance) If a difficult feeling arises, such as boredom or impatience, simply acknowledge it. Say to yourself, “Here’s a feeling of boredom” or “Here’s a feeling of impatience”. Then place those words on a leaf.

- From time to time, your thoughts will hook you, and pull you out of the exercise, so you lose track of what you are doing. This is normal and natural, and it will keep happening. As soon as you realise it’s happened, gently acknowledge it and then start the exercise again.

After instruction 9, continue the exercise for several minutes or so, periodically punctuating the silence with this reminder “Again and again, your thoughts will hook you. This is normal. As soon as you realise it, start up the exercise again.”

You can end the exercise with another round of dropping anchor, or with a simple instruction such as this: “And now, bring the exercise to an end … and sit up in your chair … and open your eyes. Look around the room … and notice what you can see and hear … and take a stretch. Welcome back!”

After doing Leaves on a Stream, debrief the exercise with the client: What sort of thoughts hooked her? What was it like to let thoughts come and stay and go without holding on? Was it hard to unhook from any thoughts in particular? Did she speed up the stream, trying to wash the thoughts away? (If so, we need to clarify: we aren’t trying to make these thoughts go away; we’re simply watching what they do.) Does she see how this is the opposite of rumination, worrying, obsessing and how it can therefore be useful in disrupting those habits?

(Harris, 2019, pp. 174-175)

The exercise helps clients learn to take a back seat, observe their thoughts as no more or less than what they are, and let them flow rather than trying to make them disappear. These thoughts can be positive, negative, or neutral. The key is that they no longer dominate the client if they are not being held onto. Clients are often invited to determine their preferred versions, such as clouds in the sky or platters on a sushi train.

Mindfulness exercises are also used to help facilitate clients’ acceptance of emotions. In the following extract, Harris (2019) demonstrates how a combination of different mindfulness techniques (observe, breathe, expand, allow, objectify, normalise, show self-compassion and expand awareness) can be used to facilitate acceptance of emotions (adapted from Harris, 2019, pp. 261-264).

Stop Overthinking: Leaves on a Stream ACT Anxiety Skill

An example of Leaves on a Stream guided meditation.

Watch

Harris – Exercise

| OBSERVE | |

| Therapist: | "Notice that feeling. Notice where it is. Notice where it’s most intense." |

| BREATHE | |

| Therapist: | "Notice that feeling and gently breathe into it." |

| EXPAND | |

| Therapist: | "See if you can open up around it - give it some space." |

| ALLOW | |

| Therapist: | "I know you don’t want this feeling, but see if you can just let it sit there for a moment. You don’t have to like it – just allow it." |

| OBJECTIFY | |

| Therapist: | "If this feeling were an object, what would it look like?" |

| NORMALISE | |

| Therapist: | "It’s completely natural and normal that you would feel this way." |

| BE SELF-COMPASSION | |

| Therapist: | "Just place a hand where you feel this most intensely – and see if you can hold it gently." |

| EXPAND AWARENESS | |

| Therapist: | "Notice the feeling, and your body, and the room around you, and you and me working here together; there’s a lot going on." |

It is common for clients to practice mindfulness exercises focused on accepting difficult emotions as their homework. The more clients practice these techniques, the easier acceptance will become for them.

Read

Reading C - Acceptance of Emotions

The table collated a brief version of this ‘acceptance of emotions’ activity. We recommend you take a moment to look at the full version with detailed explanations of each aspect in Reading C.

Besides mindfulness exercises, metaphors are also widely used to help establish psychological acceptance and defusion skills and encourage full contact with difficult psychological content. A commonly used one is called the “Struggle Switch”. As you’d notice, the metaphor is followed by a rating exercise where acceptance is talked in terms of a 0-10 scale. This is to highlight that acceptance is not an “all-or-nothing” concept. Both acceptance and struggle are best assessed and understood in terms of degree.

Struggle Switch – Exercise

| Therapist: |

Imagine that at the back of our mind is a "struggle switch." When it's switched on, it means we're going to struggle against any physical or emotional pain that comes our way; whatever discomfort shows up, we'll try our best to get rid of it or avoid it. Suppose what shows up is anxiety. (We adapt this to the client's issue: anger, sadness, painful memories, urges to drink, and so on.) If my struggle switch is on, then I absolutely have to get rid of that feeling! It's like, "Oh no! Here's that horrible feeling again. Why does it keep coming back? How do I get rid of it?" So now I've got anxiety about my anxiety. In other words, my anxiety just got worse. "Oh, no, It's getting worse! Why does it do that?" Now I'm even more anxious. Then I might get angry about my anxiety: "It's not fair. Why does this keep happening?" Or I might get depressed about my anxiety: "Not again. Why do I always feel like this?" And all these secondary emotions are useless, unpleasant, unhelpful, and a drain on my energy and vitality. And then – guess what? I get anxious or depressed about that! Spot the vicious cycle? But now, suppose my struggle switch is off. In that case, whatever feeling shows up, no matter how unpleasant. I don't struggle with it. So anxiety shows up, but this time I don't struggle. It's like, "Okay, here's a knot in my stomach. Here's tightness in my chest. Here's sweaty palms and shaking legs. Here's my mind telling me a bunch of scary stories." And it's not that I like it or want it. It's still unpleasant. But I'm not going to waste my time and energy struggling with it. Instead I'm going to take control of my arms and legs and put my energy into doing something that's meaningful and life-enhancing. So with the struggle switch off, our anxiety levels are free to rise and fall as the situation dictates. Sometimes it’ll be high, sometimes low; sometimes it will pass on by very quickly, and sometimes it will hang around. But the great thing is, we’re not wasting our time and energy struggling with it. So we can put our energy into doing other things that make our lives meaningful. But switch it on, and it’s like an emotional amplifier— we can have anger about our anger, anxiety about our anxiety, depression about our depression, or guilt about our guilt. (At this point, check in with the client: “Can you relate to this?”) Without struggle, we get a natural level of discomfort, which depends on who we are and what we’re doing. But once we start struggling with it, our discomfort levels increase rapidly. Our emotions get bigger, and stickier, and messier, hang around longer, and have more of a negative influence over us. So if we can learn how to turn off that struggle switch, it makes a big difference. And what I’d like to do next, if you’re willing, is to show you how to do that. |

| With the metaphor, we introduce a simple way to measure “degrees” of acceptance (as opposed to treating it as an all-or-nothing concept). A 0 on the struggle scale correlates with maximal acceptance, whereas a 10 means maximal avoidance. A 5 is the halfway point we call tolerance, or putting up with it. The next step then is to work with a painful emotion and actively practice lowering the struggle switch. (We may not be able to turn it all the way down to zero, but even lowering it a little is a good start). The following transcript illustrates this. | |

| The therapist has just finished asking the client to scan her body and identify where she’s feeling her anxiety most intensely. | |

| Therapist: | (Summarizing) Okay, so there’s a lump in your throat, tightness in your chest and churning in your stomach. And which of these bothers you the most? |

| Client: | Here. (Client touches her throat). |

| Therapist: | Okay. And on a scale from 0 to 10, if 0 is no anxiety at all and 10 is sheer terror, how would you rate this? |

| Client: | About an 8. |

| Therapist: | Okay. So remember that struggle switch we talked about? (Client nods.) Well, right now, would you say that it is on or off? |

| Client: | On! |

| Therapist: | Okay. Suppose we turn it into a scale of 0 to 10. 10 is full on, out and out struggle – I have to get rid of this feeling no matter what; 0 is no struggle at all – I don’t like this feeling, but I am not going to struggle with it – and 5 is the halfway point, what we might call tolerance or putting up with it. On that scale, how much are you struggling with this feeling right now? |

| Client: | About a 9. |

| Therapist: | Okay. So a lot of struggle going on right now. Let’s see if we can bring it down a couple of notches. We may or may not be able to, but let’s give it a go. |

| (The therapist now takes the client through several parts of the Acceptance of Emotions exercise described: observe like a curious child, breathe into it, notice and name it, expand around it. Then he checks in with the client to see what’s happening.) | |

| Therapist: | So what’s happening with the struggle switch? |

| Client: | Well, I feel less anxious. |

| Therapist: | Okay, we will come to that in a moment. What I’m interested in now is the struggle. On a scale of 0 to 10, how much are you struggling with this feeling? |

| Client: | Oh, about a 3. |

| Therapist: | About a 3. Now you mentioned that your anxiety is less. |

| Client: | Yes, it’s gone down a bit. |

| Therapist: |

Interesting. Well, enjoy that when it happens; at times, when you drop the struggle with anxiety, it does reduce. But that’s not what we’re trying to achieve here. Our aim is to drop the struggle. Would you be willing to keep going? See if we can get the struggle switch down another notch or two? |

(Harris, 2019, p. 264-266)

The Struggle Switch - By Dr. Russ Harris

Dr. Russ Harris, explains the struggle switch metaphor through this entertaining and educational clip. Answer the question that follows.

watch

Additional Metaphors for Acceptance

There are many other metaphors that ACT practitioners can use to promote acceptance in clients. Many metaphors used are relevant to more than one ACT core process. For example, you have learned about the “pushing away paper” exercise in Reading B and “struggling in quicksand”, which are both useful for introducing acceptance.

For additional metaphors, do a quick search online for “wade through the swamp”, “passengers on the bus”, and “demons on the boat” metaphors.

For a different learning experience, you may also find a range of animated or voiced-over versions of ACT metaphors on platforms such as YouTube (for example, Struggle Switch).

Defusion and acceptance are difficult processes and ones that ACT practitioners usually work on with clients throughout the counselling process. As such, ACT practitioners often assign clients homework to help with these processes. For example, the counsellor may ask clients to complete a worksheet such as the ‘Getting Hooked’ to help facilitate the defusion process or the 'Struggling vs. Opening Up' worksheet to help facilitate the acceptance process (Harris, 2021).

Getting Hooked – Worksheet

| GETTING HOOKED – How’s Your Mind Hooking You? |

|---|

|

Our minds are great at coming up with “stories”. In technical terms, we call such stories “cognitions”. Cognitions can include thoughts, beliefs, narratives, ideas, attitudes, assumptions, opinions, judgements, and more. Many of these stories all too easily “hook” us: they take our attention away from where it needs to be or jerk us around and pull us into self-defeating patterns of behaviour (“away moves”). There are many different categories of such stories. The following are four of the most common ones. For each category, please write in your answers. |

| Judgements (What judgements does your mind make about yourself, others, life, the world, your body, your mind, your behaviour, etc.?) |

| Time Traveling (What stories about the past – e.g. painful memories - or the future – e.g. worrying, predicting the worst - does your mind tend to hook you with?) |

| Reason Giving (What reasons does your mind give you as to why you can’t or shouldn’t do the things that matter to you?) |

| Rules (What unhelpful rules does your mind insist upon, in terms of what you can, can’t, should or shouldn’t do; or how life, the world, others should or shouldn’t be?) |

Struggling vs. Opening Up – Worksheet

| STRUGGLING VS. OPENING UP | |||

|---|---|---|---|

|

Date/Time Feelings/Sensations What events triggered this? |

How much did you struggle with these feelings? 0 = no struggle, 10 = maximum struggle. What did you actually do during the struggle? |

Did you open up and make room for these feelings, allowing them to be there even though they were unpleasant? If so, how did you do that? |

What was the long-term effect of the way you responded to your feelings? Did it enhance or worsen it? |

Techniques to Explain and Encourage Self-As-Context

ACT practitioners use various techniques to help clients understand that they are not their thoughts (or feelings, memories, urges, etc.). One commonly used metaphor is the “Sky and Weather” metaphor.

Sky and Weather – Metaphor

| Therapist: |

"Your noticing self is like the sky. Thoughts and feelings are like the weather. The weather changes continually, but no matter how bad it gets, it cannot harm the sky in any way. The mightiest thunderstorm, the most turbulent hurricane, and the most severe winter blizzard - these things cannot hurt or harm the sky. And no matter how bad the weather, the sky always has room for it—and sooner or later the weather always changes. Now, sometimes we forget the sky is there, but it's still there. And sometimes we can't see the sky—it's obscured by clouds. But if we rise high enough above those clouds—even the thickest, darkest, thunderclouds—sooner or later we'll reach clear sky, stretching in all directions, boundless and pure. More and more, you can learn to access this part of you: a safe space inside from which to open up and make room for difficult thoughts and feelings; a safe viewpoint from which to step back and observe them." |

(Harris, 2019, p. 293)

Sky Metaphor

This video explains the Sky Metaphor in practical detail.

Watch

There is also a range of experiential exercises that counsellors can use with clients to help them develop their sense of self-as-context. One of these is the 'Continuous You' exercise.

Continuous You – Exercise

What follows is a much-shortened version of the classic Observer Self exercise from Hayes and colleagues (1999), often known as the "continuous you" exercise. The exercise seems complex, but it comprises five repeating instructions:

- Notice X.

- There is X— and there’s a part of you noticing X.

- If you can notice X, you cannot be X.

- X is a part of you; and there’s so much more to you than X.

- X changes continually; the part of you noticing X does not change.

X can include some or all of the following: your breath, your thoughts, your feelings, your physical body, the roles you play. With most clients, I run through the entire exercise in one go, which takes about fifteen minutes, but you can break it up into smaller sections and debrief each one as you go. I always conclude this exercise with the Sky and the Weather Metaphor, which usually has a strong impact.

| Therapist: |

"I invite you to sit up straight, with your feet flat on the floor, and either fix your eyes on a spot or close them ... Notice the breath flowing in and out of your lungs ... notice it coming in through the nostrils ... down into the lungs ... and back out again ... And as you do that, be aware you're noticing ... there goes your breath ... and there you are noticing it. (Pause 5 seconds) If you can notice your breath, you cannot be your breath. (Pause 5 seconds) Your breath changes continually ... sometimes shallow, sometimes deep ... sometimes fast, sometimes slow ... but the part of you that notices your breath does not change. (Pause 5 seconds) And when you were a child, your lungs were so much smaller ... but the you who could notice your breathing as a child is the same you who can notice it as an adult. Now that gets your mind whirring, analyzing, philosophizing, debating ... So take a step back and notice, where are your thoughts? ... Where do they seem to be located? .... Are they moving or still? ... Are they pictures or words? ... (Pause 5 seconds) And as you do notice your thoughts, be aware you're noticing ... there go your thoughts ... and there you are noticing them. (Pause 5 seconds) If you can notice your thoughts, you cannot be your thoughts. (Pause 5 seconds) Your thoughts change continually ... sometimes true, sometimes false ... sometimes positive, sometimes negative ... sometimes happy, sometimes sad ... but the part of you that notices your thoughts does not change. (Pause 5 seconds) And when you were a child, your thoughts were so very different than they are today ... but the you who could notice your thoughts as a child is the same you who notices them as an adult. (Pause 5 seconds) Now I don't expect your mind to agree to this. In fact, I expect throughout the rest of this exercise your mind will debate, analyze, attack, or intellectualize whatever I say, so see if you can let those thoughts come and go like passing cars, and engage in the exercise no matter how hard your mind tries to pull you out of it.. (Pause 5 seconds) Now notice your body in the chair ... (Pause 5 seconds) And as you do that, be aware you're noticing ... there is your body ... and there you are noticing it. (Pause 5 seconds) It's not the same body you had as a baby, as a child, or as a teenager ... You may have had bits put into it or bits cut out of it ... You have scars, and wrinkles, and moles and blemishes, and sunspots ... it's not the same skin you had in your youth, that's for sure ... But the part of you that can notice your body never changes. (Pause 5 seconds) As a child, when you looked in the mirror, your reflection was very different than it is today ... but the you who could notice your reflection is the same you that notices your reflection today. (Pause 5 seconds) Now quickly scan your body from head to toe, and notice the different feelings and sensations ... and pick any feeling or sensation that captures your interest ... and observe it with curiosity ... noticing where it starts and stops ... and how deep in it goes ... and what its shape is ... and its temperature ... And as you notice this feeling or sensation ... just be aware you're noticing ... there is the feeling ... and there you are noticing it. (Pause 5 seconds) If you can notice this feeling or sensation, you cannot be this feeling or sensation. (Pause 5 seconds) Your feelings and sensations change continually ... sometimes you feel happy, sometimes you feel sad ... sometimes you feel healthy, sometimes you feel sick ... sometimes you feel stressed, sometimes relaxed ... but the part of you that notices your feelings does not change. (Pause 5 seconds) And when you're frightened, angry, or sad in your life today ... the you who can notice those feelings is the same you that could notice your feelings as a child. Now notice the role you're playing in this moment ... and as you do that, be aware you're noticing ... right now, you're playing the role of a client ... but your roles change continuously ... at times, you're in the role of a mother/father, son/daughter, brother/sister, friend, enemy, neighbor, rival, student, teacher, citizen, customer, worker, employer, employee, and so on. (Pause 5 seconds) And of course, there are some roles that you will never have again ... like the role of a young child ... and the role of a confused teenager (Pause 5 seconds) But the you who notices your roles does not change ... It's the same you that could notice your roles – and all the things you say and do in them – even when you were very young. We don't have a good name in everyday language for this part of you ... I'm going to call it the noticing self, but you don't have to call it that ... you can call it whatever you like.... and this noticing self is like the sky. (Finish the exercise with the Sky and the Weather Metaphor.)" |

(Harris, 2019, pp. 295-297)

The Continuous You

An example of the continuous you guided meditation.

Watch

Techniques to Promote Contact with the Present Moment

Mindfulness techniques are central in the ACT approach for helping clients contact with their present-moment experience. Mindfulness can be practiced in sessions with the client and set formally and informally for homework. Whilst there isn’t a consensual definition, formal mindfulness typically refers to setting aside time for mindfulness activities, such as meditation, whereas informal mindfulness involves bringing the concept of mindfulness to daily activities (e.g., mindfully washing dishes, mindfully brushing teeth).

Many of the previous techniques you have learned about encompass mindfulness exercises. All the techniques that require the client to focus on their breathing and allow thoughts to come and go help facilitate contact with the present-moment experience. ACT practitioners also teach clients mindfulness techniques they can use outside sessions to continue connecting with the present moment. One quick and simple mindfulness technique that is often taught to clients is the ‘Take Ten Breaths’ Technique.

Take Ten Breaths – Technique

This is a simple exercise to center yourself and connect with your environment. Practice it throughout the day, especially any time you find yourself getting caught up in your thoughts and feelings.

- Take ten slow, deep breaths. Focus on breathing out as slowly as possible until the lungs are completely empty—and then allow them to refill by themselves.

- Notice the sensations of your lungs emptying. Notice them refilling. Notice your rib cage rising and falling. Notice the gentle rise and fall of your shoulders.

- See if you can let your thoughts come and go as if they’re just passing cars, driving past outside your house.

- Expand your awareness: simultaneously notice your breathing and your body. Then look around the room and notice what you can see, hear, smell, touch, and feel.

(Harris, 2009, p. 171)

Mindfulness of breath Meditation

An example of the mindfulness of breath meditation.

Watch

Mindfully Eating a Raisin - Technique

It can also be useful to help the client understand that fully engaging in their experiences leads to increased life satisfaction and fulfilment. One commonly used technique for this is 'Mindfully Eating a Raisin'.

| Therapist: |

Throughout this exercise, all sorts of thoughts and feelings will arise. Let them come and go, and keep your attention on the exercise. And whenever you notice that your attention has wandered, briefly note what distracted you, and then bring your attention back to the raisin. Now take hold of the raisin, and observe it as if you're a curious scientist who has never seen a raisin before ... (The ellipses represent pauses of five seconds.) Notice the shape, the colors, the contours ... Notice that it's not just one color—there are many different shades to it ... Notice the weight of it in your hand and the feel of its skin against your fingers ... Gently squish it and notice its texture ... Hold it up to the light, and notice how it glows ... Now raise it to your nose and smell it ... and really notice the aroma ... And now raise it to your mouth, rest it against your lips, and pause for a moment before biting into it ... And notice what's happening inside your mouth ... Notice the salivation ... Notice the urge to bite ... And in a moment—don't do it yet—I'm going to ask you to bite it in half, keeping hold of one half and letting the other half drop onto your tongue ... And so now, in ultraslow motion, bite the raisin in half, and notice what your teeth do ... and let the raisin sit there on your tongue for a moment ... and I invite you to close your eyes now, to enhance the experience ... And just notice any urges arising ... And then gently explore the raisin with your tongue, noticing the taste and the texture ... And now, in ultraslow motion, eat the raisin and notice what your teeth do ... and your tongue ... and your jaws ... and notice the changing taste and texture of the raisin ... and the sounds of chewing ... and notice where you can taste the sweetness on your tongue ... and when the urge to swallow arises, just notice it for a moment before acting on it ... and when you do swallow, notice the movement and the sound in your gullet ... and then notice where your tongue goes and what it does ... and after you've swallowed, pause ... and notice the way the taste gradually fades ... but still faintly remains ... and then, in your own time, eat the other half in the same way. |

Afterwards, debrief the exercise: “What did you discover?” “What interested you most?” Then we can ask. “So what is the relevance of this exercise for your life?” Through questioning the client – and providing the answers if he doesn’t come up with any – we now draw out (a) how we take things for granted and fail to appreciate them, and (b) how, when we really pay attention, life is so much more interesting and fulfilling.

Clients commonly comment with amazement on how much taste and flavor there is in one raisin, and how much activity goes on in the mouth. Ask your client how she usually eats raisins, and she'll usually mime chucking a whole handful into her mouth. Use this exercise as a metaphor for life – how much richer it is when we're mindful.

(Harris, 2009, pp. 163-164)

Reflect

How comfortable do you feel about using the mindfully eating a raisin exercise with yourself and/or clients? Some people will replace raisins with other food, and the same concept can be applied to other items or activities that promote savouring skills.

Remember that ACT practitioners practise what they ask clients to practise. It is important for you to try and practise these strategies before using them with clients.

Mindful Eating MEDITATION

An example of mindfully eating a raisin meditation.

Watch

Techniques to Help to Clarify Values

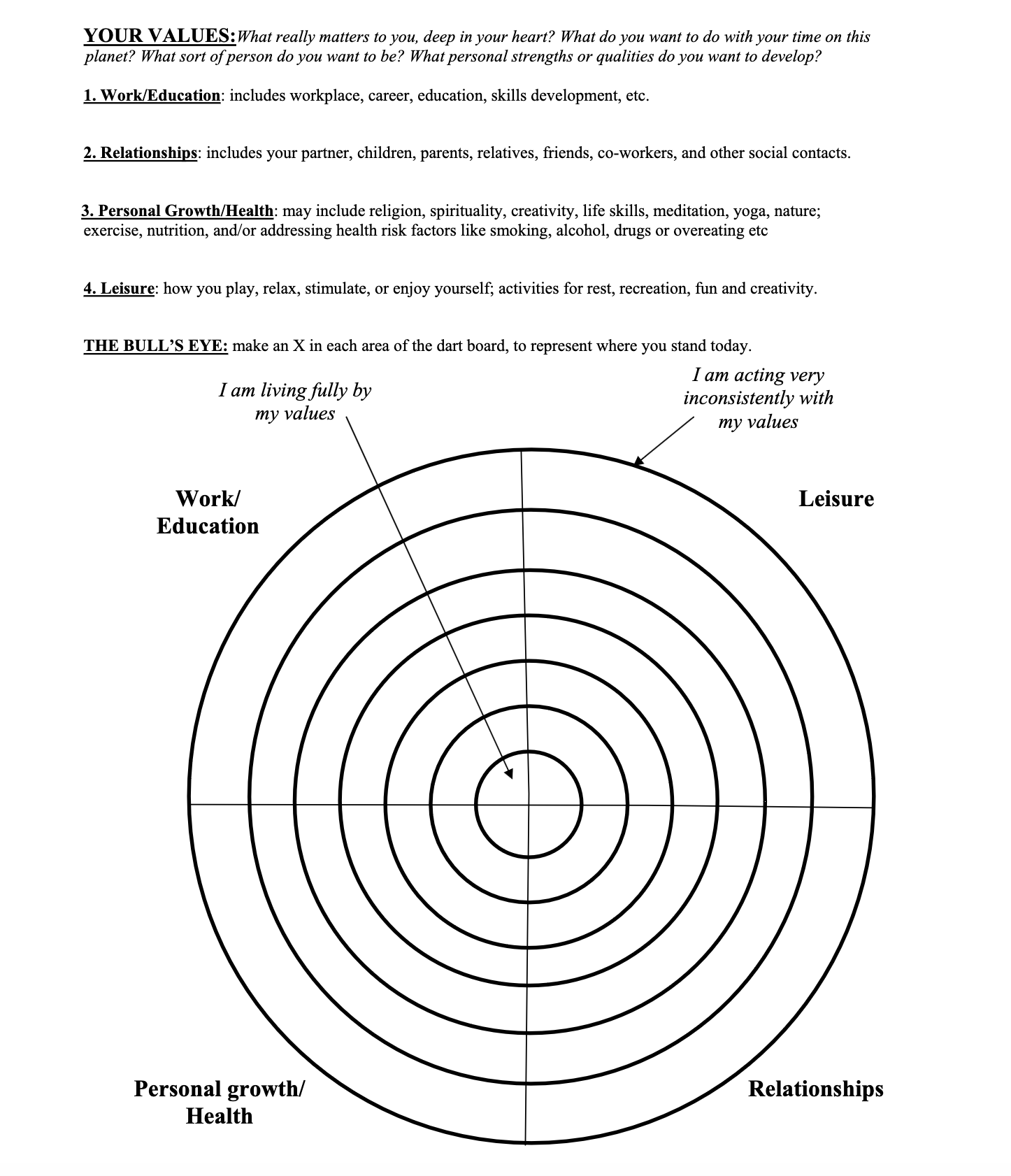

Clarifying the client’s values is an important step in the ACT counselling process. Some clients may have clearer ideas of what they want and have been engaging in value-driven activities, while others may require help clarifying their values. There are a range of worksheets that ACT counsellors use during this process. One of them is the following downloadable Bull's Eye Worksheet (pdf) (Harris, 2007).

Bull's Eye Worksheet

Reflect

Take some time to complete these worksheets yourself. Did you find it useful for clarifying your values? Which of the worksheets do you prefer? Why?

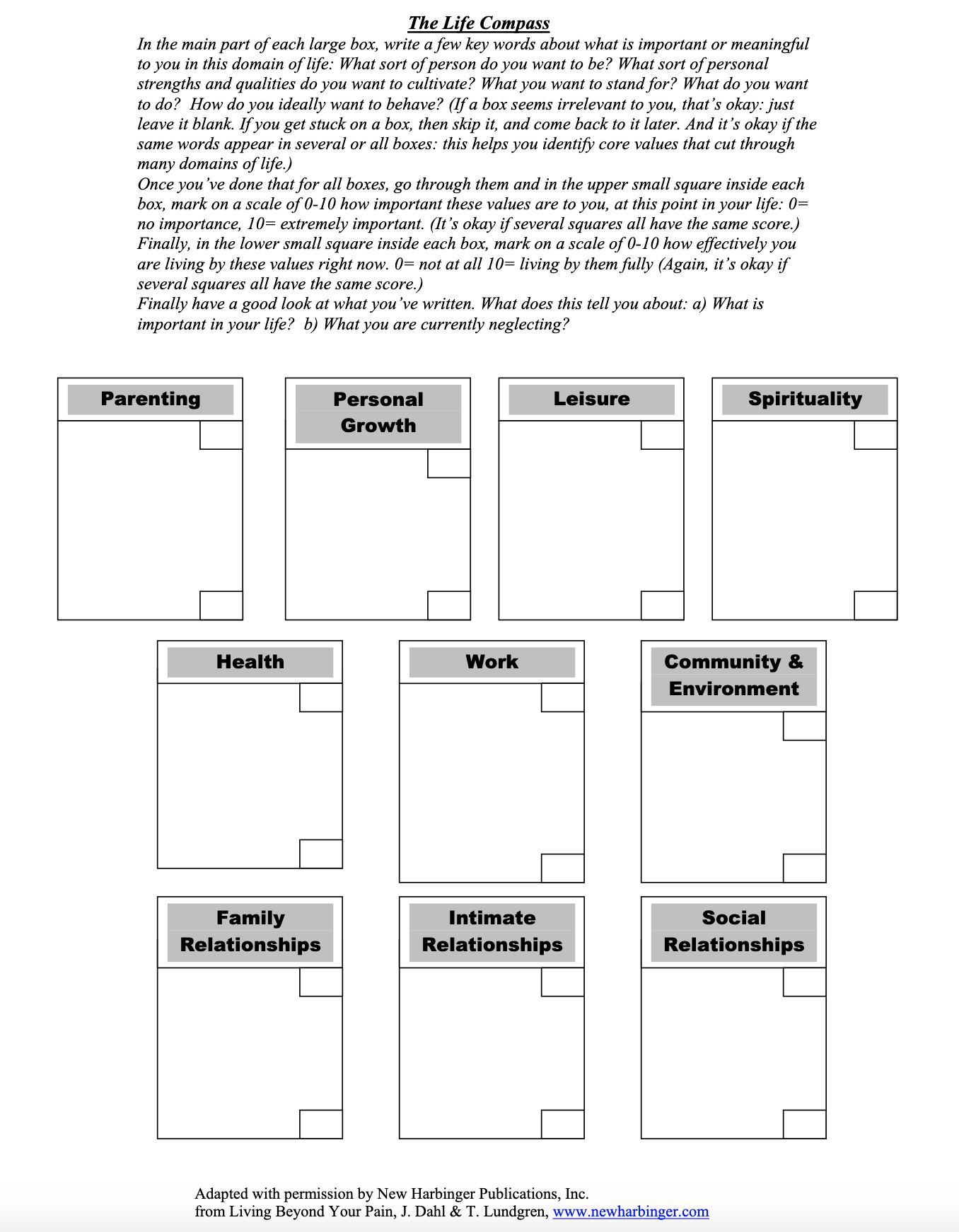

Life Compass – Worksheet

Another commonly used worksheet is the following Life Compass (pdf) (New Harbinger Publications, Inc.).

Some clients find it difficult to think about their values in this sort of format, so another technique that is often used to clarify values is the 'Imagine your Eightieth Birthday' technique.

Imagine your Eightieth Birthday – Technique

| Therapist: | "So I'm going to ask you to imagine your eightieth birthday and to imagine that three different people stand up to make speeches about you. And keep in mind; this is a fantasy—an imaginary exercise—, so it doesn't have to follow the rules of logic and science. You can be eighty, but your friends may look exactly as they do today. And you can have people there who are already dead or who'll be dead by the time you're eighty. And if you want to have children one day, then you can have your children there. Also, keep in mind you aren't trying to realistically predict the future. You're creating a fantasy—if magic could happen so that all your dreams come true—then what would your eightieth birthday look like? So if your mind starts interfering and saying things like, People don't mean what they say at these events or No, that person would never say that about me, then just say "Thanks, mind" and come back to the exercise. Okay?" |

| Client: | "Okay." |

| Therapist: | "Okay. So I invite you to get into a comfortable position, and either close your eyes or fix them on a spot ... and for the next few breaths, focus on emptying your lungs ... pushing all the air out ... and allowing them to fill by themselves ... Notice the breath flowing in and flowing out ... in through the nostrils ... down into the lungs .... and back out ... Notice how, once the lungs are empty, they automatically refill ... And now, allowing your breath to find its own natural rate and rhythm ... no need to keep controlling it ... I'd like you to do an exercise in imagination ... to create a fantasy of your ideal eightieth birthday ... not to try and realistically predict it but to fantasize how it would be in the ideal world, if magic could happen and all your dreams came true ... So it's your eightieth birthday, and everyone who truly matters to you friends, family, partner, parents, children, colleagues ... anyone and everyone whom you truly care about, even if they’re no longer alive, is gathered in your honor ... This might be a small intimate affair in a family home or a huge affair in a classy restaurant ... it’s your imagination, so create it the way you want it ... Now imagine that one person whom you really care about – friend, child, partner, parent, you choose – stands up to make a speech about you ... a short speech, no more than three or four sentences ... and they talk about what you stand for in life ... what you mean to them ...and the role that you have played in their life ... and imagine them saying whatever it is deep in your heart that you would most love to hear them say. (Pause for 40 to 50 seconds)" |

The therapist now repeats this for two other people – always allowing the client to choose who will speak – and each time allowing forty to fifty seconds of silence for reflection.

| Therapist: | Most people find this exercise brings up a whole range of feelings, some warm and loving and some very painful. So take a moment to notice what you’re feeling ... and consider what these feelings tell you ... about what truly matters to you ... what sort of person you want to be ... and what, if anything, you’re currently neglecting ... (Pause 30 seconds) And now, bringing the exercise to an end ... and notice your breathing ... and notice your body in the chair ... and notice the sounds you can hear ... and open your eyes and notice what you can see ... and take a stretch ... and notice yourself stretching ... and welcome back! |

Afterwards, we debrief the exercise in detail: What happened? What did people say about you? What does this tell you about what matters to you, what you want to stand for, and what sort of person you want to be?

(Harris, 2009, pp. 202-203)

Once the client is aware of their values, the counsellor and client can focus on using these values to help them set specific goals that can lead to committed action.

Imagine your 80th Birthday

An example of the Imagine your 80th Birthday technique.

Watch

Techniques to Facilitate Committed Action

Committed action involves any purposeful actions that help the client pursue their values. Depending upon the client's needs, this might involve using some form of traditional behavioural interventions, or it may simply involve committing to valued living. Of course, making changes is a difficult process, so ACT counsellors help their clients anticipate potential barriers and learn how to respond effectively to them.

Our clients, just like us, often fail to follow through on doing things that will make life better. We want to normalize and validate this, identify what’s getting in the way, and come up with effective strategies to overcome the barriers. The HARD acronym— Hooked, Avoiding discomfort, Remoteness from values, and Doubtful goals— is a good way for you and your clients to remember and identify common barriers to action.

(Harris, 2019, p. 288)

A Technique to Help Clients Take Action Using ACT

The presenter discusses a common question regarding clients that are stuck, "why can't I get my client to take committed action? Why is it so difficult?". Answer the question that follows.

Watch

HARD – Worksheet

The following ‘HARD” worksheet (Harris, 2021) is designed to help clients clarify their internal barriers to change.

The aim of this worksheet is to clarify your own internal barriers, holding you back from stepping out of your comfort zone, or trying new things, or facing your fears, or tackling your big challenges, etc.

There are two ways to fill out this worksheet. One option is to do it for a specific domain of life, for example, work, education, friends, partner, parenting, spirituality, hobbies and health. The other option is to do it as a broad overview of life in general.

Check your understanding of the content so far!

Learn More ACT Techniques

The techniques discussed in this section are only a sample of the boundless range of available ACT techniques. Conduct your own online research to learn about more ACT techniques. As a starting point, a range of worksheets and other ACT resources are freely available at ACT Mindfully Workshops with Russ Harris - Free Resources.

Check your understanding of the content so far!

Like most other approaches to counselling, the therapeutic relationship is considered to be of central importance to the effectiveness of ACT. In ACT, the counsellor is not considered an ‘expert’; instead, the counsellor and client are considered as equals. Counsellors are encouraged to practice the same concepts and techniques that they teach their clients and admit that they, too, have had difficulties with avoidance, fusion, and lack of values clarity (Batten, 2011). Indeed, many ACT explanations and metaphors highlight this by having the counsellor remind the client that they, like the client, are struggling with life’s challenges. For example, the counsellor might say something like:

You know, a lot of people come to therapy believing that the therapist is some sort of enlightened being, that he’s resolved all his issues, he’s got it all together— but that’s not the way it is. It’s more like you’re climbing your mountain over there, and I’m climbing my mountain over here. And from where I am on my mountain, I can see things on your mountain that you can’t see— like there’s an avalanche about to happen, or there’s an alternative pathway you could take, or you’re not using your pickaxe effectively.

But I’d hate for you to think that I’ve reached the top of my mountain, and I’m sitting back, taking it easy. Fact is, I’m still climbing, still making mistakes, and still learning from them. And basically, we’re all the same. We’re all climbing our mountain until the day we die. But here’s the thing: you can get better and better at climbing, and better and better at learning to appreciate the journey. And that’s what the work we do here is all about.

(The Two Mountains Metaphor; Harris, 2019, p. 54)

When working from an ACT approach, it is important to remember that:

- The ACT therapist speaks to the client from an equal, vulnerable, compassionate, genuine, and sharing point of view and respects the client’s inherent ability to move from unworkable to workable responses.

- The therapist is willing to self-disclose when it serves the interest of the client.

- The therapist avoids the use of formulaic ACT interventions, instead fitting interventions to the particular needs of particular clients. The therapist is ready to change course to fit those needs at any moment.

- The therapist tailors interventions and develops new metaphors, experiential exercises, and behavioral tasks to fit the client’s experience and language practices and the social, ethnic, and cultural context.

- The therapist models acceptance of challenging content (e.g., what emerges during treatment) while also being willing to hold the client’s contradictory or difficult ideas, feelings, and memories without any need to resolve them.

- The therapist introduces experiential exercises, paradoxes, or metaphors as appropriate and deemphasizes literal sense making of the same.

- The therapist always brings the issue back to what the client’s experience is showing and does not substitute his or her opinions for that genuine experience.

- The therapist does not argue with, lecture, coerce, or attempt to convince the client.

- ACT-relevant processes are recognized in the moment and, where appropriate, are directly supported in the context of the therapeutic relationship.

(Adapted from Luoma, Hayes & Walser, 2017, pp. 317-320)

Read

Reading D - Core Competencies of the ACT Therapeutic Stance

The therapeutic relationship increases clients’ psychological flexibility during the ACT process. Reading D discusses the nine core competencies of ACT practitioners listed in more detail.

ACT is a very ‘active’ form of counselling that requires clients to engage in various mindfulness and experiential exercises. Clients must participate in therapeutic techniques and reflect upon their thought processes. The counsellor guides the client; however, the client must learn to “be present, open up, and do what matters” (Harris, 2019, p. 9).

Read

Reading E - Embracing Your Demons

Reading E is a classic article from Russ Harris that provides an overview of ACT – from its goal, differences from other mindfulness-based behavioural therapies, and the integral concepts and interventions. A brief case study is also included at the end to demonstrate the processes of ACT.

Check your understanding of the content so far!

The Benefits of the ACT Approach for Suitable Clients

Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) is a widely recognised counselling approach with proven effectiveness for many clients and various client issues. However, it's important to acknowledge that ACT may not suit everyone. In this context, we will explore the benefits of the ACT approach for clients well-suited to this therapeutic framework.

One of the key benefits of ACT for suitable clients is the enhancement of psychological flexibility. ACT empowers clients to develop greater emotional regulation, adaptability, and resilience. Clients learn to accept and mindfully embrace their thoughts and emotions, reducing the struggle against them. This improves mental well-being as clients gain the skills to navigate life's challenges more easily.

Another significant advantage of ACT is its ability to guide clients toward increased value-based living. Suitable clients engage in the process of clarifying their deeply held values and committing to actions aligned with those values. This shift towards a more values-driven life fosters a sense of purpose and meaning. Clients often experience increased life satisfaction and greater fulfilment as they align their actions with their values.

In addition to psychological flexibility and value-based living, ACT can lead to a reduction in avoidance behaviours. Suitable clients learn to acknowledge how past coping strategies, particularly avoidance, may have cost them. Learning to accept difficult emotions and situations rather than avoiding them. This can result in personal growth, reduced life experience, and suffering related to avoidance. Clients become better equipped to recognise difficulties and accept challenging situations, leading to a more empowered and resilient mindset.

Furthermore, ACT can have a positive impact on interpersonal relationships. Suitable clients often find that their ability to communicate effectively, empathise with others, and navigate interpersonal conflicts improves significantly. This enhancement in interpersonal skills contributes to healthier relationships and greater social well-being.

In summary, the ACT approach offers numerous benefits for clients well-suited to its principles. These benefits include increased psychological flexibility, pursuing a more meaningful and values-driven life, reduced avoidance behaviours, and improved interpersonal relationships. ACT can be a powerful and transformative approach for clients seeking a therapeutic framework that emphasises mindfulness, acceptance, and commitment to valued actions.

Check your understanding of the content so far!

This module section explored the theoretical underpinnings and key techniques of acceptance and commitment therapy. It is important for any counsellor who intends to use ACT techniques to understand these concepts because theoretical understanding is vital for the effective practice of ACT. You will learn more about how counsellors implement ACT in the next section of this module.

- Batten, S. V. (2011). Essentials of acceptance and commitment therapy. London, UK: Sage.

- Ciarrochi, J. A., & Bailey, A. (2008). A CBT practitioner’s guide to ACT: How to bridge the gap between Cognitive Behavioural Therapy and Acceptance & Commitment Therapy. Oakland, CA: New Harbinger Publications.

- Flaxman, P. E., Blackledge, J. T., & Bond, F. W. (2011). Acceptance and commitment therapy. East Sussex, UK: Routledge.

- Harris, R. (2006). Embracing your demons: An overview of Acceptance and Commitment Therapy. Psychotherapy in Australia, 12(4), pp. 2-8.

- Harris, R. (2019). ACT made simple: A quick start guide to ACT basics and beyond. New Harbinger.

- Harris, R. (2021). ACT made simple: The extra bits. https://www.actmindfully.com.au/free-stuff/worksheets-handouts-book-chapters/

- Lloyd, J., & Bond, F. W. (2015). Acceptance and commitment therapy. In S. Palmer (Ed.), The beginner’s guide to counselling and psychotherapy (2nd ed.). Sage.

- Luoma, J. B., Hayes, S. C., & Walser, R. D. (2017). The ACT therapeutic stance. In Learning ACT: An acceptance and commitment therapy skills-training manual for therapists (3rd ed.) (pp. 317-319). Context Press.

- Stoddard, J. A., & Afari, N. (2014). The big book of ACT metaphors: A practitioner’s guide to experiential exercises & metaphors in acceptance & commitment therapy. Oakland, CA: New Harbinger.