Trigger warning

Students studying palliative care, please be aware that the content you are about to engage with may include discussions, images, or descriptions related to death, dying, and end-of-life care. These topics can be emotionally challenging and may trigger feelings of sadness, grief, or discomfort. It's essential to approach this material with self-care in mind, and if you find it distressing or overwhelming, consider reaching out to your Trainer and Assessor or support system. Remember that studying palliative care is a crucial step in providing compassionate end-of-life care, but your emotional well-being is equally important.

Introduction

Depending on your work role and industry sector, you will need a range of skills to use a palliative care approach and to support palliative care services to your clients. You will need to identify your clients’ needs when they are faced with serious, life-threatening illness, or when they are reaching the end of their lives, and to assess and report changes in their needs so that you can contribute to palliative care services and supports.

People with terminal illnesses and those who are facing end of life have care and support needs that address the whole person: physical, psychological, emotional, social, cultural and spiritual. Palliative care endeavours to address all these needs to maintain the best possible quality of life in the person’s last days and so that they have the best possible death.

Unconscious Bias

An important aspect of providing care, especially when you are working with people whose values, beliefs and cultural traditions may be different from your own, is to avoid unconsciously expressing your own biases and perspectives. Remaining non-judgmental is a key ethical principle.

Unconscious bias refers to the automatic, ingrained attitudes or stereotypes we hold about certain groups based on factors like race, gender, age, or socioeconomic status. These biases can shape our perceptions, decisions, and behaviours without our conscious awareness. In the context of care, unconscious bias can lead to unequal treatment, miscommunication, and reduced quality of care for certain individuals or groups

We need to be aware of the non-verbal messages we send unconsciously via our body language, reactions and responses when we see or hear something that conflicts our personal values and beliefs. These messages can have a significant impact on clients and their families and can present barriers to them expressing their needs, feelings, and preferences openly and honestly. Sometimes it is better to be open and identify differences in beliefs and values honestly while at the same time expressing acceptance for diversity and supporting the rights of everyone to have their own values, beliefs, and preferences acknowledged and respected.

Case Study

Susie is a support worker in a residential aged care facility. One of the residents, Jane Smith, has an advance care directive in place. In the directive, Jane has expressed her wish to be buried in a cardboard coffin so that her body will decay quickly and will provide ‘food for the worms’ and have no negative impacts on the environment, and so that her body will ‘return to the earth from which it came.’ Jane does not believe in the afterlife, and she does not wish her burial place to have any marker. Susie finds this unsettling, as she has strong beliefs about the resurrection of the body at judgment day. She also finds the notion of a body decaying and being eaten by worms quite disgusting. Susie tries not to let her facial expressions, tone of voice, or body posture express her feelings when Jane is talking about her burial plans, but Jane notices that Susie flinches a little and asks her what the matter is. After thinking for a moment, Susie tells Jane that she finds the idea of being buried in a cardboard coffin disturbing, and that she does believe in an afterlife and in resurrection of the body. They talk about this for a while and Susie tells Jane about her own wish to have a ‘proper’ Christian funeral and burial. Jane and Susie agree that while their beliefs are different, they both support the right of everyone to have their wishes respected.

Needs of People Dealing with a Life-Limiting Illness

The physical needs of someone experiencing a life-limiting illness encompass a range of requirements to address their comfort, symptom management, and overall well-being. These needs may include pain management, symptom control, assistance with daily activities, access to medical care, and support for maintaining comfort and quality of life.

Emotional needs can vary widely from person to person, and support should be tailored to the individual's preferences and circumstances. Emotional needs often include psychological support, coping strategies, and assistance in managing anxiety, depression, fear, and grief. Individuals may require opportunities to express their feelings and fears in a supportive environment.

Financial needs can vary widely depending on the individual's specific diagnosis, treatment plan, insurance coverage, and personal circumstances Financial needs may include medical expenses, home care costs, and loss of income due to illness. Individuals may benefit from financial counselling, assistance programs, and planning for end-of-life expenses.

Individuals receiving a diagnosis of a life-limiting illness often experience a range of emotional responses, including shock, fear, anxiety, sadness, anger, confusion, and sometimes a sense of numbness or disbelief. These emotions can vary widely depending on the individual and the nature of the diagnosis. It's essential to remember that everyone's emotional response is unique.

Remember that the specific needs of individuals dealing with a life-limiting illness can vary widely, and it's important to tailor support and care to each person's unique circumstances and preferences. Open communication and a multidisciplinary approach involving healthcare providers, caregivers, and support services can help meet these needs effectively.

The needs can be further explained as:

1. Physical Comfort:

- Individuals need relief from pain, symptoms, and discomfort related to their illness.

- Proper pain management, symptom control, and assistance with daily activities are essential.

2. Emotional Support:

- Emotional distress is common, and individuals require support to cope with fear, anxiety, sadness, and uncertainty.

- Providing a safe space for expression, active listening, and emotional validation is crucial.

3. Communication and Information:

- Clear and honest communication about their condition, treatment options, and prognosis is essential.

- People need information to make informed decisions about their care and future plans.

4. Autonomy and Control:

- Maintaining a sense of control over their lives becomes crucial.

- Involvement in care decisions and respecting their preferences are vital.

5. Psychosocial and Spiritual Support:

- Support to address psychological and spiritual needs is necessary.

- Having access to counselling, spiritual guidance, and opportunities for reflection can be valuable.

6. Family and Social Relationships:

- Maintaining connections with loved ones and social networks is important.

- Support workers should facilitate family discussions and provide opportunities for shared moments.

7. End-of-Life Planning:

- People need assistance with advance care planning, including decisions about medical treatments and end-of-life wishes.

- Having conversations about their preferences can bring peace of mind.

In this topic we will examine physical care and treatment for pain and other symptoms.

Although your role may not include providing direct nursing or medical care and treatment, it will be important for you to have a basic understanding of these so that you can support the work of nurses and medical staff, and so that you are able to explain and provide accurate information to family members, carers and others.

You will also need to understand the person’s treatments for pain and other conditions so that you can observe and report any changes in their needs and responses.

Pain and Pain Management

What do we mean by pain?

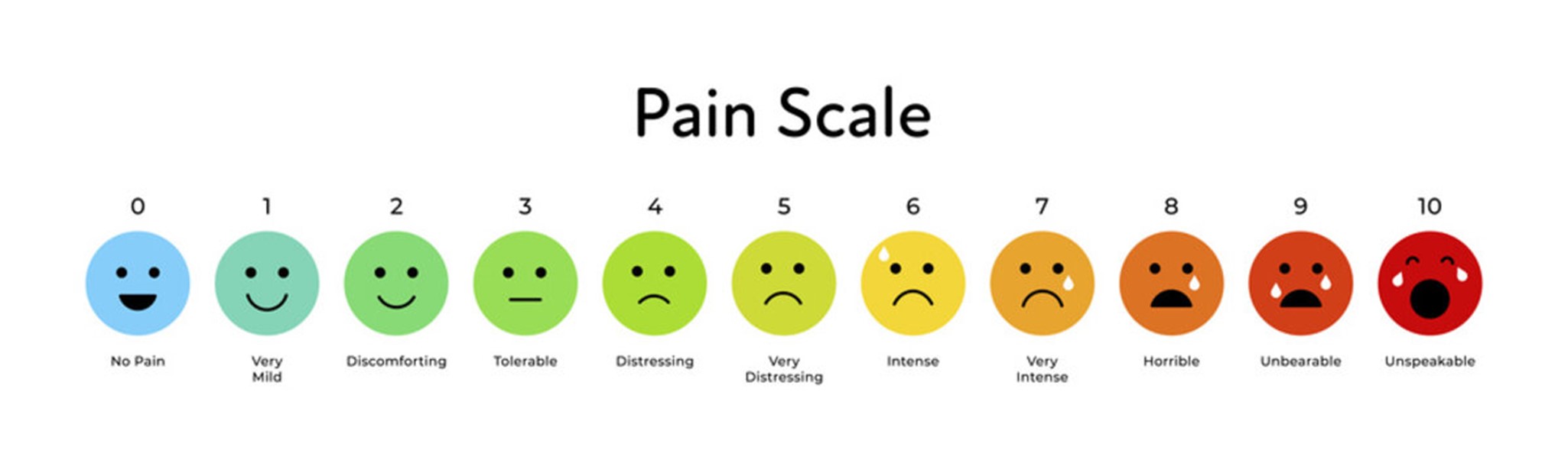

Feeling pain is a complex process that includes physical, sensory and emotional experiences that occur when your body is injured or damaged. Your nerve cells send messages to your brain, which then sends messages back to your body. These messages create the sensation of pain. Experiencing pain is subjective; it is difficult to observe pain except through a person’s behaviour and through what they report about how they are feeling. Each individual may experience pain differently, which is why pain measurement scales (such as the one below) are used.

The Role of the Brain in the Experience of Pain

The brain plays a significant role in the experience of pain. Current approaches to managing and treating pain include psychological strategies and techniques as well as physical and chemical (medication) treatments.

Pain is said to be a ‘warning’ intended to draw attention to an injury so that you can protect your body from harm. When an injury occurs, your nervous system sends messages to your brain, which assesses the danger and prompts you to act.

Recent research in neuroscience indicates that in the case of chronic pain the brain becomes over-sensitised to pain signals so that it is in a state of constant alert and the sensation of pain becomes self-perpetuating – that is, because you expect to be in pain, you continue to experience pain. Emotion and thought plays a significant role in this process. Negative emotions and thoughts tend to increase or intensify the subjective experience of pain, and positive emotions and thoughts tend to decrease it. This means that in addition to medication, psychological strategies such as cognitive behavioural therapy and meditation can be effective in managing severe and chronic pain.

Pain Management

Unless your role is in nursing or paramedics, you are unlikely to be directly involved in administering pain medications. But it is still important for you to have a broad understanding of pain management strategies and treatments so that you can support clients and so that you are able to observe changes in their comfort and responses. If you have any questions or concerns about your clients’ pain management treatments, seek advice from an appropriate health professional or your supervisor. You should also be aware of regulations controlling the use and storage of some pain medications.

A range of strategies and techniques can be used to manage pain.

These include:

- medication

- physical treatments such as massage, exercise, hydrotherapy, using heat packs or ice packs • psychological therapies such as relaxation, cognitive behaviour therapy (CBT) and meditation

- occupational therapy

- support groups

- alternative therapies such as acupuncture.

Pain Relief and comfort provision

Pain relief is a crucial component of palliative care. The goal is to effectively manage and alleviate pain, enhancing the patient's comfort and overall quality of life. This may involve medication, therapies, and other interventions tailored to the individual's needs. Comfort promotion in palliative care encompasses a wide range of measures beyond pain relief. It includes addressing physical discomfort, managing symptoms, providing emotional support, facilitating communication, and creating a peaceful environment aligned with the patient's preferences.

Maintaining the person’s overall comfort is a key aim of palliative care. Comfort is a very subjective concept affected by different factors. The degree of comfort that we experience is changeable and can accentuate, but includes feeling cared for, valued, safe and having choices.

These are some key aspects of comfort:

- Freedom from, or reduction of, physical pain and emotional distress.

- Feeling positive, safe, and strong.

- Feeling confident and in control of care and treatments.

- Feeling cared for and valued, with positive connections to people and place.

- Seeking Guidance from health professional regarding pain relief and comfort provision

Seeking clarification and guidance from a health professional regarding pain relief and comfort provision is an important step in managing your health or the health of a loved one. Here's a step-by-step process to help you navigate this:

- Identify the Need for Clarification

Recognise when one requires clarification or guidance on pain relief and comfort provision in the context of palliative care. This might involve person experiencing uncontrolled pain, discomfort, or uncertainty about the available options. - Contact Primary Healthcare Provider

Reach out to the persons primary healthcare provider, such as general practitioner (GP) or specialist, who is familiar with the medical history. Explain the situation and concerns about pain relief and comfort provision. - Request a Consultation

Request a consultation specifically focused on discussing pain relief and comfort provision in the context of palliative care. This may involve scheduling an appointment with the healthcare provider or seeking a referral to a palliative care specialist. - Prepare for the Consultation

Before the consultation, gather relevant information about the patient's medical history, current symptoms, and any medications being taken. Prepare a list of questions you have about pain management and comfort in palliative care. - Attend the Consultation

Attend the scheduled consultation with the healthcare provider. During the appointment, share your concerns, ask your questions, and provide any relevant information. Be open about preferences and values. - Discuss Pain Management Options

Engage in a thorough discussion about pain relief options. This may include medications, therapies, and interventions that can help manage pain effectively. Ask about potential side effects and how to adjust treatments based on the patient's response. - Explore Comfort Provision Strategies

Inquire about strategies to enhance comfort provision beyond pain management. This could involve addressing symptoms, emotional support, counselling services, and creating a conducive environment for the patient. - Understand the Care Plan

Request a clear explanation of the care plan tailored to the patient's specific needs and preferences. Understand the roles of different healthcare professionals involved in the palliative care team. - Ask for Additional Resources

Ask for educational resources, pamphlets, or websites that provide more information about palliative care, pain relief, and comfort provision in Australia. This can help make informed decisions. - Discuss Follow-Up Plans

Inquire about follow-up appointments and communication channels. Establish a plan for regular check-ins to assess the effectiveness of pain relief strategies and make any necessary adjustments. - Involve Family Members

If applicable, involve family members or caregivers in the discussion. Ensure that everyone is on the same page regarding the pain relief and comfort provision plan. - Advocate for the person's needs

If you feel that person’s concerns are not adequately addressed or need further assistance, don't hesitate to advocate for their needs. Seek a second opinion or request a referral to a palliative care specialist if necessary.

Remember that clear communication and collaboration with your healthcare provider are key to ensuring the best possible pain relief and comfort provision. Don't be afraid to advocate for yourself or your loved one to receive the care and support needed for optimal comfort and well-being.

Nutrition and Hydration

For many reasons, many people receiving palliative care experience lack of appetite and weight loss. This can be due to a range of factors including physiological changes, poorly controlled pain, depression and the side effects of some medications. Other factors such as dental problems, loss of muscular function affecting the ability to chew and swallow, and decrease in sense of taste or smell, can also play a role in this.

Nutritional and hydration needs are important in palliative care as they contribute to the patient's overall comfort and quality of life. Proper nutrition and hydration can help manage symptoms, maintain energy levels, and support the body's immune system.

Here are the nutritional requirements in relation to palliative care:

- Individualised person’s needs: Each patient's nutritional needs are unique. Factors such as their medical condition, symptoms, appetite, and personal preferences must be considered when planning their diet.

- Appetite Changes: Many patients in palliative care experience reduced appetite due to their illness, medications, or emotional state. It's important to respect their desires and not force them to eat if they're not hungry.

- Nutrient-Dense Foods: Focus on providing nutrient-dense foods that offer essential vitamins, minerals, and calories. Small, frequent meals that are rich in protein, healthy fats, and fibre can help meet nutritional requirements.

- Hydration through Foods: In cases where drinking fluids might be difficult, consider offering foods with high water content, such as fruits, soups, and gelatine.

- Foods of Choice: Allow patients to choose the foods they enjoy, as this can contribute to their overall comfort and well-being. Their preferences should guide food selections.

Here are the hydration requirements in relation to palliative care:

- Hydration Importance: Adequate hydration is essential to prevent discomfort, alleviate symptoms, and maintain bodily functions. Dehydration can lead to fatigue, confusion, and exacerbation of symptoms.

- Individualised Approach: Like nutritional needs, hydration requirements vary from person to person. Some patients may require less fluid due to reduced physical activity, while others may need more due to fever or increased respiratory rate.

- Alternative Hydration Methods: For patients who have difficulty swallowing or drinking fluids, alternative hydration methods can be considered, such as offering small sips of water, using moistened swabs, or providing ice chips.

- Conscious Choices: Discussions about hydration should involve the patient and their family. Some patients may choose to limit fluids intentionally, and their decisions should be respected.

- Consideration of Goals: It's important to align hydration decisions with the patient's goals and values. In some cases, aggressive hydration may not align with the patient's desire for comfort.

Within a palliative care approach, the focus is, of course, on keeping the person as comfortable as possible and maintaining quality of life, rather than on recovery. This means that unless intervening will increase the person’s quality of life, invasive measures such as PEG feeding (percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy, where a feeding tube is put through the abdomen and into the stomach) are not used, especially in the end-of-life phase.

If maintaining nutrition and hydration is likely to improve the person’s quality of life and comfort, oral supplements, small frequent meals that include favourite foods, and nutrient-dense snacks, milk drinks, smoothies and juices can be given.

Watch

Watch the following video about the importance of Nutrition and Hydration towards end of life care.

Pain Management Plans

Pain management plans are developed between clients, carers, and palliative care teams. It is important to specify and record the goals and strategies clearly and accurately so that all parties are aware of the details of the plan and so that there is a record of what has been done, what progress has been made, what results have been achieved, and whether any changes are needed.

The plan is also essential for ensuring that everyone on the team (including the client, family members and others) are on the same page so that strategies are implemented consistently.

As a palliative care support worker, you must follow your client’s individualised care plan and pain management plan.

You can find useful information on this link regarding pain management.

Pain management plans usually include a mix of the following:

Pain-Relieving Medications

Pain medications fall into two general categories: those that reduce inflammation and those that alter messages to and from the brain.

Anaesthetics Anaesthetics can also be used to relieve pain. Local anaesthetics reduce the sensitivity of nerve endings and cause numbness, which relieves pain for a limited period of time in a specific area of the body. For example, a local anaesthetic may be used to numb the gums during dental treatment. More powerful

anaesthetics can be used to cause longer lasting numbness and cause unconsciousness or semi-consciousness. These are often used in surgical procedures.

Common Painkillers

Medications such as paracetamol, aspirin and NSAIDs reduce inflammation and pain.

Opioids

Opioid medications such as codeine, morphine and oxycodone, are used for severe pain. These are strictly regulated as they can be addictive.

Psychotropic Medications Antidepressant medications and anti-epileptic medications are also sometimes used to control or relieve pain. These also work by changing brain chemistry or altering messages to and from the brain. The choice of medication will depend on factors such as the type of pain, the location in the body, its cause, its duration and:

- the person’s overall health

- what other medications they are using (and possible interactions between medications)

- potential negative side effects (such as organ damage and addiction)

- relevant regulations (In the case of opioid medication).

All drugs have potential side effects, so choosing a pain medication will involve weighing up possible benefits against possible risks.

Physical Treatments

Physical treatments can be used in conjunction with medication, or as a stand-alone management strategy. This will also depend on the nature, cause and location of the pain. Physiotherapy, exercise and massage are often used to treat pain resulting from injury to joints and muscles, or from chronic conditions that affect joints and muscles, especially when the aim is to restore function or to slow down degeneration. Occupational therapy can analyse movements and functioning with a view to correcting and adjusting reduce pain, reduce further damage, and improve physical functioning.

Alternative Therapies

Alternative therapies such as acupuncture have been found to be effective in controlling or reducing some forms of pain.

Psychological Therapies

Psychological therapies are used to work on the connection between the brain and the experience of pain, either by helping the person to change the way they think and feel about their pain (CBT or cognitive behaviour therapy), or through inducing a more relaxed state in which the pain is experienced less intensely (meditation and relaxation techniques). One of the benefits of this approach is that the person regains some control over their experience of pain, which has psychological benefits and can create a more positive frame of mind. Our emotions and how we think about what we are experiencing plays a significant role in how we experience pain. Psychotherapy can also help address emotional and psychological pain associated with physical pain.

Care plans are important tools for recording treatments and supports for pain and other symptoms. Care plans share information within teams and ensure that services are provided consistently. Check the care plan regularly for changes. Use the care plan (if it is designed to include notes and observations) to record your activities and observations, and especially to record any changes in your client’s condition and their responses to strategies being used. Family members and significant others may also be included in a care plan. Having a copy of the care plan can reassure family members and keep them informed about services and supports and about the person’s progress.

Formats

There are many different formats used for recording care plans. Most will include sections for:

- goals of the palliative care services (which should be negotiated and agreed with the client, family, care team, and others) • strategies to be used to achieve the goals

- each team member’s responsibilities

- what resources will be required and used

- a time frame or schedule of activities and interventions • a record of progress and outcomes.

Reading

Read this article to learn more about care plans:

‘Care Plan for the Dying Person–Health Professional Guidelines’ from Queensland Health

Reporting to Supervisor and others

Reporting information about your clients’ progress and changing needs to your supervisors and other interested parties is an important aspect of providing palliative care. Your own organisation will have policies and procedures for you to follow, and there are some general principles to keep in mind.

Information can be reported verbally or in writing. Your organisation may have its own templates and formats for recording and documenting treatments and changes in clients’ needs and responses.

You can collect information about your clients’ progress and changing needs through observing, asking questions, and checking records. Recording your observations accurately and objectively is an important aspect of your role, as is reporting your observations to appropriate team members and others.

Observation

Observation collects direct behavioural evidence of your client’s physical functioning, emotional and psychological states, and general health.

Observing changes in your clients’ behaviour, appearance, functioning, and physical capacity is an important method for gathering information about their progress and about changes in their support needs.

As a direct care provider, you will be in a good position to notice changes in, for example, the amount and type of support your client needs to complete daily living tasks, changes in appetite, changes in mood, and changes in their activities and activity levels, which might indicate changes in health, pain levels and capacity.

It is important to record your observations accurately and objectively. Avoid generalisations and assumptions and give clear descriptions of behaviours with specific examples to show what you mean.

Asking Questions

Asking questions is another obvious method for collecting information about your client. Use closed questions to check facts and open questions to elicit more detailed information, such as how your client is feeling, what is working for them and what is not, and how their experiences and needs are changing.

Again, it is important to record your clients’ responses as accurately, fully, and objectively as possible. Give examples of things your client says and the words and phrases they use to show what you mean. Avoid making assumptions and giving opinions without providing some supporting evidence.

Subjective Information vs. Objective Information

When you report information to your supervisors, colleagues, family members and others, it is important to give objective information that is supported by evidence. This means that you must describe what you see and what you hear without making assumptions or trying to guess what it means.

Subjective information includes your interpretations and opinions of what you see and hear, and assumptions you make about what you see and hear, such as why a person is behaving in a particular way.

When you report information to your supervisor or others, make sure that you are reporting only what you see and hear, not what you think or feel. If you believe it is important to include interpretations of your client’s behaviour, always back these up with hard evidence or clear, accurate descriptions of what you actually saw or heard.

You must also check the care plan regularly for any changes, especially after the person has requested changes and the plan has been reviewed.

Case Study

Antonio is a support worker in a residential facility for adults with disabilities. Axel, one of the residents, has a degenerative condition that affects his muscles and will eventually affect his ability to breathe without a ventilator. His condition also causes chronic muscle pain and limits mobility. Most people with this condition have a life expectancy of approximately 25 years. Axel is now 24. He needs a wheelchair to move around and requires full physical assistance with daily living tasks such as dressing, eating and toileting. He has been experiencing severe chronic pain for the past few months and is receiving palliative care, including pain medication.

Axel recently asked Antonio to request a medication review with a view to increasing his pain medication. Axel’s parents are not in favour of increasing his pain medication because they believe it will hasten his death.

Antonio writes a report to his supervisor describing his observations of the changes in Axel: for example, his increasing need for physical support, sleep disturbances and insomnia, and outbursts of anger when he is asked to participate in routine physiotherapy exercises. Antonio includes Axel’s latest pain scale response (between 8 and 9) and reports his request for a medication review and increase in pain medication verbatim.

Antonio arranges a meeting with Axel, his parents, and his palliative care team to discuss increasing Axel’s pain relief. After hearing what the team has to say, and listening to Axel’s description of his pain levels, his parents agree that increasing his pain relief would be the best option for him.

Understanding the end-of-life phase and processes may help you to provide more effective services as well as to manage your own responses, and to support the person’s family and others.

You will need to recognise and understand signs of deterioration and signs of imminent death.

This topic will help you will understand:

- The physical processes that occur at the end of life.

- Signs that the person is deteriorating and moving towards death.

- How to follow end-of-life care strategies, including:

- Checking the care plan for any changes, especially changes to the person’s decisions.

- Providing a supportive environment at the end of life.

- Respecting the person’s preferences and cultural requirements at the end of life and following death.

- Maintaining the person’s dignity at the end of life and after death.

- Recognising signs of imminent death and reporting to an appropriate team member.

Within your work role, providing emotional support to families, carers, and others when a death has occurred.

Most of us have never been present when someone is dying. Death is one of our society’s most taboo subjects, so most of us also have very little information about what actually happens as someone is dying. We do not know what to expect, and it is a subject that we probably do not feel comfortable thinking or talking about. Dying is essentially a physical process, so we will examine the physical aspects first.

Physical death means that our organs shut down and stop functioning – digestion, respiration, beating of the heart and blood circulation all slow and stop. The brain also ceases to function. This includes parts of the brain that control involuntary functions such as breathing, and voluntary or conscious functions such as speech. Hearing is thought to be the only sense that remains until the end. Dying can take days, hours, or minutes. When a person is approaching death, they can become drowsier, weaker, lose appetite, have difficulty swallowing, become restless and occasionally confused. They may lose control of their bladder and bowels and their breathing may slow or become more laboured.

Signs of Deterioration and Imminent Death

Changes occur in the weeks and days leading up to death. These include physical, behavioural, emotional, and spiritual changes which indicate that d earth is imminent.

- Profound Weakness and Fatigue - As the body's systems begin to shut down, the person may experience extreme weakness and fatigue. They may have difficulty moving or even speaking.

- Decreased Level of Consciousness - A decrease in alertness and responsiveness is common. The person may become drowsy, unresponsive, or difficult to awaken.

- Changes in Breathing - Breathing patterns often change. Breaths may become irregular, shallow, or laboured. There might be longer gaps between breaths, known as Cheyne-Stokes breathing. Gurgling Sounds: The accumulation of saliva or fluids in the throat can lead to gurgling sounds, known as the "death rattle."

- Cool Extremities and Mottling - The hands, feet, and sometimes the skin in other areas may become cool to the touch and exhibit mottled discoloration due to reduced circulation.

- Decreased Appetite and Thirst - As the body's metabolism slows down, the person's appetite and thirst may decrease significantly. They may no longer feel the desire to eat or drink.

- Changes in Skin Colour - The person's skin tone may change to a pale skin colour. • Mottling: The appearance of a bluish or purplish marbled pattern on the skin, particularly on the extremities, due to decreased blood flow

- Inability to Swallow - Swallowing difficulties can arise as the person's muscles weaken. This can lead to an inability to consume food and fluids.

- Changes in Urination - Urinary output may decrease as the kidneys' function declines. Urine colour may become darker or more concentrated.

- Restlessness and Agitation - Restlessness, confusion, or increased agitation can occur due to changes in brain function and oxygen levels.

- Changes in Conscious Awareness - Some individuals may experience heightened consciousness or periods of clarity before passing away. They might have meaningful interactions with loved ones during this time.

- Changes in Vital Signs - These may include lowered blood pressure, slower heart rate (bradycardia), and irregular breathing patterns

- Reduced Blood Pressure: Blood pressure may drop as the body's systems slow down. This can contribute to feelings of light-headedness and a weak pulse.

- Social Withdrawal - The person may become less engaged with their surroundings and withdraw from social interactions.

- Decreased Urge to Communicate - Communication may become limited or challenging as energy levels decrease. The person may communicate less frequently or only through nonverbal cues.

- Decreased Reflexes - Reflexes may diminish as the body's nervous system becomes less responsive.

Watch

Watch this short video identifying signs of imminent death: ‘10 Signs of Death | Signs Death is Near’ from Love Lives

The psychological and emotional impact of palliative or end-of-life care

The psychological and emotional impact of palliative or end-of-life care is profound and extends to the person receiving care, their family, caregivers, and friends. Individuals receiving palliative care can experience anxiety, fear, sadness, and reflections on their life's meaning and legacy. The uncertainty of their condition and thoughts about pain can contribute to emotional challenges. The loss of physical autonomy and control over their body due to illness can be distressing. This loss of control may impact their psychological well-being.

The psychological impact on family members providing palliative care can be profound and multifaceted. Family members often experience a rollercoaster of emotions when their loved one is receiving palliative care. They may grapple with anticipatory grief, sadness, anxiety, and even guilt. The impending loss of their family member and the responsibility of caregiving can be emotionally overwhelming.

Caregivers may experience emotional exhaustion, feelings of helplessness, and guilt. The challenges of caregiving and witnessing a loved one's decline can lead to emotional strain. The responsibility of providing palliative care, combined with the uncertainty of the situation, can lead to substantial psychological and emotional impact such as heightened levels of anxiety and depression.

Friends and close acquaintances of a person receiving palliative or end-of-life care can be significantly impacted emotionally and psychologically due to the unique challenges and emotional intensity of the situation. Friends and acquaintances can feel helpless, sad, and uncertain about how to support the person and their family. They may also experience their own grief about the impending loss.

End of life care Strategies

End-of-life care strategies mainly focus on providing comfort, dignity, and support to individuals during their final stages of life these include the following:

- Pain and Symptom Management: Prioritise effective pain management and symptom relief to ensure that patients are comfortable and free from distressing symptoms. This involves tailoring medications and interventions to address specific symptoms like pain, nausea, and shortness of breath.

- Open and Honest Communication: Maintain clear and open communication between healthcare providers, patients, and their families. Discuss the prognosis, treatment options, and possible outcomes to ensure everyone is well-informed and prepared.

- Respect for Wishes: Prioritise the patient's wishes and preferences regarding medical interventions, treatment plans, and end-of-life decisions. Ensure that their values and choices are respected and honoured.

- Holistic Approach: Address not only the physical needs but also the emotional, psychological, social, and spiritual well-being of patients. Offer counselling, therapy, and support services to address these various aspects of care.

- Hospice Care: Consider transitioning patients to hospice care when curative treatments are no longer effective. Hospice focuses on providing comfort, emotional support, and symptom management in the patient's preferred setting, often at home.

- Advance Care Planning: Encourage patients to engage in advance care planning discussions, documenting their wishes and preferences for medical care in case they cannot communicate later on. This helps ensure that their desires are known and respected.

- Family Involvement: Involve family members in care discussions, decisions, and planning. Offer emotional support and provide them with the information they need to understand the patient's condition and contribute to the care process.

- Emotional and Psychological Support: Provide counselling, therapy, and support groups for both patients and their families. Address emotional challenges, anxiety, grief, and other psychological aspects of coping with end-of-life situations.

- Creating a Comfortable Environment: Ensure a peaceful, soothing, and comfortable physical environment for the patient. Use calming elements like soft lighting, soothing music, and familiar objects to create a serene atmosphere.

- Spiritual and Religious Care: Offer spiritual care through chaplains or spiritual counsellors to address the spiritual and existential needs of patients and their families. Respect and facilitate religious practices as desired.

- Quality of Life Focus: Prioritise activities and experiences that enhance the patient's quality of life, even in the face of limited time. This could involve fulfilling personal wishes, spending time with loved ones, or engaging in meaningful activities.

- Coordination of Care: Ensure effective coordination among healthcare providers, specialists, and caregivers to provide seamless care. This prevents unnecessary interventions and streamlines the care process.

- Cultural Sensitivity: Consider cultural and religious beliefs when providing care, ensuring that practices align with the patient's background and preferences.

- Regular Assessment: Continuously assess the patient's physical, emotional, and psychological well-being to adjust care plans as needed and ensure that their comfort and needs are met.

- Dignity and Respect: Treat patients with dignity and respect at all times, honouring their autonomy, choices, and individuality.

End-of-life care is a complex and delicate phase, and these strategies collectively aim to provide a compassionate, comprehensive, and holistic approach to support individuals and their families during this significant time. The ultimate aim of an end-of-life care plan is to ensure that the person has a good quality of life when facing serious illnesses, which generally means that the person dies in the way that they wish to and is without pain or discomfort.

There are several elements in providing support to ensure the comfort of a person which can include:

- The person’s preferences for how they die are met as far as possible.

- Spiritual and religious elements are addressed.

- The emotional wellbeing of the person and those close to them is supported.

- The person is able to die feeling that their life was completed.

- Quality of life was as good as possible in the period before death.

- The person’s preferences for treatment have been respected and met.

- Changes in the person’s needs were identified and responded to appropriately.

- The person was able to die with dignity.

- Family members were included in the process (in accordance with the person’s wishes and preferences).

In short, the person was able to die according to their own wishes and without avoidable pain, discomfort, or distress.

Case Study

James

James was diagnosed with melanoma in his early forties. After apparently successful treatment, the cancer returned two years later, and James was told it had advanced beyond the stage where it could be cured or effectively treated, and that he could expect only months more of life. James discussed this with his family, and with the help of a palliative care service, they made an advance care plan that included his will and arrangements for financial and property matters, palliative care and pain management, end-of-life strategies, and funeral arrangements.

James expressed a wish to die at home with his wife and children present, and his family agreed to this. He stated that he did not wish to be resuscitated and that he wanted to be cremated and his ashes scattered in a favourite camping spot. He did not wish for any religious ceremonies or services but asked that his favourite music be played at his cremation.

James remained at home with palliative care and support until his death. In the days before he died, he spent time with his family and with close friends, talking about his life and his achievements.

On the day that James died, his wife and children sat with him until he asked them to leave him alone for a little while so that he could sleep. A support worker remained with him, and he asked her to tell his wife that he was too tired to stay awake any longer and that he wanted to go. He asked the support worker to hold his hand and passed away peacefully.

James’ wife and children were upset when they found that he had died while they were out of the room, but when they heard what the support worker had to say they felt a bit better. James’ wife commented that she believed that James had asked her to leave so that she could let him go.

Watch

What really matters at the end of life | BJ Miller’ from TED

An advance care directive should include plans for taking care of the body after the person dies. There may be cultural or religious requirements for handling the body, and your organisation will have policies and procedures to follow to maintain workplace health and safety and for infection control.

At all times, the person’s dignity must be preserved in the way their body is handled. This may include covering the body and placing screens around the bed, or moving the body to a quiet place, especially if death occurs in a semi-public setting such as shared accommodation.

Certifying Cause of Death

Depending on circumstances, a medical or health professional may be present to record the time of death and to identify the cause of death. In most states and territories, all deaths must be notified to the Registry of Births, Deaths, and Marriages, usually within 48 hours.

In a palliative care context, it is not usually necessary to notify police or the coroner of the person’s death (unless there are suspicious circumstances) and the person’s attending doctor can examine the body to determine cause of death and complete a death certificate and notify the Registry. If a doctor is not available within the 48-hour period, this can result in some complications. Check your state or territory requirements for notification of deaths and your own organisation’s policies and procedures.

If the death occurs in the person’s home, carers and family members may contact the palliative care service involved, or a funeral director. Any doctor may complete the death certificate as long as they know the person’s medical history and are willing to verify the cause and manner of the person’s death.

Infection Control Precautions

Follow your organisation’s infection control precautions when handling a dead body. These will include:

- Wear appropriate PPE (personal protective equipment) such as disposable gloves, water repellent gown or apron, mask, and eye protection (goggles or face shield).

- Avoid contact with blood or body fluids

- Cover any wounds or abrasions (yours) with waterproof bandages.

- Do not eat or drink.

- Avoid touching your eyes.

- Follow strict personal hygiene including washing hands with soap and water or alcohol rub before and after touching the body, avoiding sharps injury, and disposing of sharps and contaminated bedding.

- Dispose of PPE afterwards.

- Always wash hands thoroughly afterwards.

It may also be necessary to clean, disinfect or sanitise surfaces and equipment, and any linen should be washed and disinfected. If the person was known to have an infectious condition, follow your organisation’s procedures and guidelines for managing and controlling the spread of this.

Personal Effects and Belongings

Personal effects and belongings of the deceased person should be handled with care and respect. Depending on the family's preferences and legal requirements, these items can be returned to the family, preserved for sentimental reasons, or handled in accordance with the deceased person's wishes.

Your organisation will have policies and procedures for safeguarding and disposing of the person’s belongings and personal effects. many organisations would have specific policies and procedures to document the personal belongings of the deceased person it is advisable to create a detailed inventory of the personal effects and belongings. This inventory should include descriptions of items, photographs if possible, and any relevant information, such as sentimental value or instructions from the deceased person. These instructions may be included in the person’s advance care directive or will.

Personal effects often include articles that are precious mementos for family and others, so they must be kept safe and handled carefully.

Cultural and Religious Requirements

It is essential to respect the cultural, spiritual, and religious beliefs of the deceased person and their family. This may involve specific rituals, ceremonies, or practices associated with their culture or faith. These customs should be accommodated to the best of your ability. The person’s advance care directive or their funeral arrangements may specify cultural and religious requirements. If not (and depending on your work role), discuss these with the person’s family, next of kin, and others. You may be able to offer practical assistance with arrangements, and you may also be able to offer a friendly ear for people to confide in and talk to as part of supporting people with grief.

State and Territory Legal Requirements

State/Territory medico-legal requirements are laws and regulations specific to each Australian state or territory governing the handling and management of deceased persons. It is crucial to be aware of these requirements to ensure that all legal obligations, including death certification and reporting, are met when caring for the deceased person's body.

State and territory laws in Australia can differ in terms of death registration processes, autopsy requirements, and the documentation needed for transporting and handling deceased individuals. These differences necessitate an understanding of the specific regulations in the relevant jurisdiction.

State and Territory-based Medico-legal Requirements for caring for deceased persons Body:

NSW-The NSW Health Guideline for the Management of the Deceased Patient

Guides care and handling of deceased person's body. Medico-legal requirements include:

1. Confirmation of Death: • A qualified medical professional, such as a doctor or nurse, confirms the death. In some cases, this may require multiple assessments to ensure accuracy.

2. Documentation: • Complete necessary documentation, including the death certificate. Accurate and thorough record-keeping is essential for legal and administrative purposes.

3. Cause of Death Determination: • Determine and document the cause of death. This may involve a post-mortem examination or autopsy, depending on the circumstances and legal requirements.

4. Infection Control Measures: • Implement appropriate infection control measures to protect those handling the deceased body. This includes using personal protective equipment (PPE) and following established protocols.

5. Preservation Techniques: • If the body will not be immediately released for burial or cremation, preserve it using proper techniques, such as refrigeration or embalming. Preservation helps maintain the body's condition.

6. Transportation Precautions: • Take precautions during the transportation of the deceased body to prevent contamination or injury. This may involve placing the body in a secure and sealed container. 7. Cultural and Religious Sensitivity: • Be aware of and respect cultural and religious practices related to death and the deceased body. This includes considerations for handling, preparation, and rituals.

8. Autopsy Procedures: • If an autopsy is required, follow established procedures for conducting a thorough examination. Autopsies are often performed to determine the cause of death or gather forensic evidence.

9. Tissue and Organ Donation: • In cases where the deceased person has expressed a desire for organ or tissue donation, facilitate the donation process in accordance with legal and ethical guidelines.

10. Forensic Requirements: • If the death is under investigation or deemed suspicious, follow forensic procedures. This may involve collaboration with law enforcement and forensic experts.

11. Legal Compliance: • Ensure compliance with local, state, and national laws governing the handling of deceased bodies. This includes obtaining necessary permits and authorizations.

12. Communication with Family: • Communicate sensitively with the family of the deceased, providing information about medical procedures, cause of death, and any relevant findings.

Victoria -The Victorian Institute of Forensic Medicine

provides guidelines for the handling of deceased persons. Medico legal requirements include:

1. Post-Mortem Examinations: • Protocols for conducting post-mortem examinations, including the examination process and documentation of findings.

2. Death Verification: • Procedures for confirming and verifying the death of an individual.

3. Documentation and Records: • Guidance on accurate and thorough documentation of post-mortem examinations, including necessary forms and records.

4. Evidence Collection: • Protocols for the collection, preservation, and documentation of evidence during post-mortem examinations.

5. Release of the Body: • Procedures for the release of the deceased person's body to relevant authorities or funeral directors.

6. Family and Cultural Considerations: • Recognition of the need for sensitivity to the cultural and religious practices of the deceased person and their family.

7. Communication: • Guidance on communicating findings to relevant authorities, law enforcement, and family members.

8. Staff Training and Professionalism: • Requirements for ongoing staff training and maintaining a high level of professionalism in the handling of deceased individuals.

Queensland- Queensland Health provides guidelines for the care of deceased persons. Medico legal requirements include:

1. Death Verification: • Procedures for confirming and verifying the death of an individual.

2. Post-Mortem Examinations: • Protocols for conducting post-mortem examinations, including examination procedures and documentation requirements.

3. Documentation and Records: • Guidance on accurate and thorough documentation of post-mortem examinations and related records.

4. Release of the Body: • Procedures for the release of the deceased person's body to relevant authorities or funeral directors.

5. Family and Cultural Considerations: • Recognition of the need for sensitivity to the cultural and religious practices of the deceased person and their family.

6. Communication: • Guidelines on communicating findings to relevant authorities, law enforcement, and family members.

7. Staff Training and Professionalism: • Requirements for ongoing staff training and maintaining a high level of professionalism in the handling of deceased individuals.

Western Australia-The Department of Health provides guidelines for funeral directors and the handling of deceased persons.

1. Death Verification: • Training on the procedures and criteria for verifying and confirming a person's death.

2. Cultural Sensitivity: • Understanding and respecting diverse cultural and religious practices related to death and mourning.

3. Documentation: • Training on the accurate and comprehensive documentation of post-mortem examinations and related procedures.

4. Communication Skills: • Developing effective communication skills when interacting with grieving families and relevant authorities.

5. Legal and Ethical Considerations: • Understanding the legal and ethical obligations related to the handling of deceased persons.

6. Post-Mortem Procedures: • Specific training on post-mortem examination procedures, including techniques and safety measures.

7. Grief Support: • Providing support and empathy to grieving families and individuals.

8. Occupational Health and Safety: • Ensuring that staff are aware of and adhere to occupational health and safety guidelines when handling deceased persons.

South Australia- SA Health provides guidelines for the care and handling of deceased persons.

1. Death Certification: • Proper procedures for certifying the cause of death.

2. Post-Mortem Procedures: • Training on conducting post-mortem examinations, if applicable.

3. Cultural Sensitivity: • Understanding and respecting cultural and religious practices related to death and handling deceased individuals.

4. Legal and Ethical Considerations: • Knowledge of relevant laws and ethical guidelines regarding the handling of deceased persons.

5. Communication Skills: • Effective communication with families, law enforcement, and other relevant parties.

6. Infection Control: • Adherence to strict infection control measures to ensure the safety of staff and others.

7. Documentation: • Proper documentation of post-mortem examinations and related procedures.

8. Occupational Health and Safety: • Training on maintaining a safe and healthy work environment.

Northern Territory- The Department of Health provides guidelines for mortuary services.

1. Confirmation of Death: • A qualified medical professional, such as a doctor or nurse, confirms the death. In some cases, this may require multiple assessments to ensure accuracy.

2. Documentation: • Complete necessary documentation, including the death certificate. Accurate and thorough record-keeping is essential for legal and administrative purposes.

3. Cause of Death Determination: • Determine and document the cause of death. This may involve a post-mortem examination or autopsy, depending on the circumstances and legal requirements.

4. Infection Control Measures: • Implement appropriate infection control measures to protect those handling the deceased body. This includes using personal protective equipment (PPE) and following established protocols.

5. Preservation Techniques: • If the body will not be immediately released for burial or cremation, preserve it using proper techniques, such as refrigeration or embalming. Preservation helps maintain the body's condition.

6. Transportation Precautions: • Take precautions during the transportation of the deceased body to prevent contamination or injury. This may involve placing the body in a secure and sealed container.

7. Cultural and Religious Sensitivity: • Be aware of and respect cultural and religious practices related to death and the deceased body. This includes considerations for handling, preparation, and rituals.

8. Autopsy Procedures: • If an autopsy is required, follow established procedures for conducting a thorough examination. Autopsies are often performed to determine the cause of death or gather forensic evidence.

9. Tissue and Organ Donation: • In cases where the deceased person has expressed a desire for organ or tissue donation, facilitate the donation process in accordance with legal and ethical guidelines.

10. Forensic Requirements: • If the death is under investigation or deemed suspicious, follow forensic procedures. This may involve collaboration with law enforcement and forensic experts.

11. Legal Compliance: • Ensure compliance with local, state, and national laws governing the handling of deceased bodies. This includes obtaining necessary permits and authorizations.

12. Communication with Family: • Communicate sensitively with the family of the deceased, providing information about medical procedures, cause of death, and any relevant findings.

ACT- ACT Health provides guidelines for mortuary services.

1. Confirmation of Death: • A qualified medical professional, such as a doctor or nurse, confirms the death. In some cases, this may require multiple assessments to ensure accuracy.

2. Documentation: • Complete necessary documentation, including the death certificate. Accurate and thorough record-keeping is essential for legal and administrative purposes.

3. Cause of Death Determination: • Determine and document the cause of death. This may involve a post-mortem examination or autopsy, depending on the circumstances and legal requirements.

4. Infection Control Measures: • Implement appropriate infection control measures to protect those handling the deceased body. This includes using personal protective equipment (PPE) and following established protocols.

5. Preservation Techniques: • If the body will not be immediately released for burial or cremation, preserve it using proper techniques, such as refrigeration or embalming. Preservation helps maintain the body's condition.

6. Transportation Precautions: • Take precautions during the transportation of the deceased body to prevent contamination or injury. This may involve placing the body in a secure and sealed container. 7. Cultural and Religious Sensitivity: • Be aware of and respect cultural and religious practices related to death and the deceased body. This includes considerations for handling, preparation, and rituals.

8. Autopsy Procedures: • If an autopsy is required, follow established procedures for conducting a thorough examination. Autopsies are often performed to determine the cause of death or gather forensic evidence.

9. Tissue and Organ Donation: • In cases where the deceased person has expressed a desire for organ or tissue donation, facilitate the donation process in accordance with legal and ethical guidelines.

10. Forensic Requirements: • If the death is under investigation or deemed suspicious, follow forensic procedures. This may involve collaboration with law enforcement and forensic experts.

11. Legal Compliance: • Ensure compliance with local, state, and national laws governing the handling of deceased bodies. This includes obtaining necessary permits and authorizations.

12. Communication with Family: • Communicate sensitively with the family of the deceased, providing information about medical procedures, cause of death, and any relevant findings.

Documentation requirements

Documentation requirements may include a death certificate, medical certificates, permits for burial or cremation, and transportation permits if the body needs to be moved between states or territories. Accurate records of the deceased person's identity and the circumstances of their death must also be maintained.

The documentation requirements may include:

- Death certificate or medical certificate of the cause of death.

- Consent forms for post-mortem examinations, if applicable.

- Burial or cremation permits.

- Any documentation related to organ donation, if applicable.

- Identification and personal information of the deceased person.

There are often timeframes within which documentation and reporting must be completed. These timeframes can vary by state or territory. It is essential to be aware of and adhere to the specific deadlines to ensure compliance with the law.

A medical practitioner is typically responsible for issuing the medical certificate of the cause of death. This certificate is a crucial part of the documentation required for the deceased person. It should accurately reflect the cause of death and be completed promptly.

Supporting the Person’s Family and Friends

Emotional support can be provided by offering condolences, listening empathetically to their feelings and concerns, and allowing them to grieve in their own way and at their own pace. Providing a compassionate presence and being available to talk or provide comfort can be immensely valuable.

If you have been a regular carer or support for the person, you will probably be in a good position to offer emotional support to family and friends.

This can include:

- being there and listening

- sharing your memories of the person

- offering practical assistance with arrangements

- providing information about what happens after a death, and about the procedures that are followed

- offering referral to counselling and grief support services • perhaps attending the funeral service if you are invited.

Keeping in touch with family and others for a while after the death may also be helpful but check that the family want this first.