In this topic, we focus obesity, its relation to cardiovascular disease and the significance of physical activity. You will learn about:

- Obesity and its contributing factors

- Theories of obesity

- Physical activity and its benefits

- Obesity and cardiovascular disease

- Health and exercise recommendations.

Terminology and vocabulary reference guide

As an allied health professional, you need to be familiar with terms associated with basic exercise principles and use the terms correctly (and confidently) with clients, your colleagues, and other allied health professionals. You will be introduced to many terms and definitions. Add any unfamiliar terms to your own vocabulary reference guide.

Activities

There are activities throughout the topic and an end of the topic automated quiz. These are not part of your assessment but will provide practical experience that will help you in your work and help you prepare for your formal assessment.

Overweight and obesity are defined as abnormal or excessive fat accumulation that presents a risk to healthWorld Health Organisation

Obesity is caused by an increase in size and amount of fat cells in the body. The number of fat cells is typically determined via genetics, established in the early years, and does not alter significantly throughout adult life. The size of fat cells, however, can be altered through diet and lifestyle modifications, the bad news being, fat cells, like all cells of the body, have a memory and will typically aim to return to the size they remember/feel comfortable at.

There are many factors which can contribute towards obesity, some within and some out with an individuals’ control such as lifestyle, genetics, and environment as well as medical conditions. Look Well what was that noise at the following possible influencing factors which can be a contributing factor towards increased levels of fat tissue, these can be useful educational tools for your clients.

The following points are some examples of contributing factors (but not limited to):

- Diet

- Lack of exercise

- Factors in a person’s environment

- Genetics

- Medical conditions

- Medication

- Stress or depression

- Change of routine.

Behaviour is a huge factor influencing weight gain, from the type of food, the size of the portion, eating when not hungry or being attracted to calorie-dense, nutritionally low (yet tasty) foods. The follow demonstrates lifestyle choices which can both rapidly and significantly contribute to increased levels of adipose tissue.

- Increased energy intake

- Decreased energy output via work activity requirements, leisure time or incidental activity

- Increased portion sizes

- Increased intake of fatty foods

- Increased intake of sugars from food products or soft drinks

- Increased alcohol consumption

- Increased food varieties & palatability.

It is also important to be aware of the numerous environmental influences which impact diet behaviours and choices. Some of these environmental influences include tantalising advertising, competitions related to fast food options, price point (fast food is typically much more affordable than its wholefood alternatives) and what friends and family are eating. This highlights that there are several factors which contribute to rising obesity levels.

- Biological factors - hunger, appetite, and taste

- Economic factors - income, availability, cost

- Psychological factors - mood, guilt, stress

- Physical factors - skills (cooking/ preparation requirements), time, access to desired foods

- Social factors - friends, family or peers, culture, meal patterns.

- Environmental factors - special offers, deals, promotions, advertising

Take a look at the following video which discusses removing fast food advertising from television screens before 9 pm to reduce the influence these have on children, their education and behaviours, particularly during the COVID -19 pandemic which sees an increase in children, and adults, at home and watching television.

Environmental, genetic, or medical

As there are several variables which contribute towards rising obesity levels, it is difficult to determine one single contributing factor. Is it due to lifestyle? A pre-disposition to store body fat (“thrifty genotype”) or an underlying medical condition such as diabetes?

New Zealand’s obesity statistic

New Zealand has the third highest adult obesity rate in the OECD, and our rates continue to increase.NZ Ministry of Health

The New Zealand Health Survey 2019/20 reported the following statistics regarding obesity levels in both adults and children:

Adults

- Around 1 in 3 adults (aged 15 years and over) were obese (30.9%)

- The prevalence of obesity among adults differed by ethnicity, with 63.4% of pacific, 47.9% of Māori, 29.3% of European/other and 15.9% of Asian adults obese

- Adults living in the most socioeconomically deprived areas were 1.8 times as likely to be obese as adults living in the least deprived areas (adjustments made for age sex and ethnicity)

- The overall prevalence has remained relatively stable since 2012/13, however, there was an increase between 2011/12 and 2019/20 for adults aged 45–54 years and 55–64 years.

Children

- Around 1 in 10 children (aged 2–14 years) were obese (9.4%)

- The prevalence of obesity among children differed by ethnicity, with 29.1% of pacific and 13.2% of Māori obese, followed by 3.4% of Asian and 7.2% of European/other children

- Children living in the most socioeconomically deprived areas were 2.7 times as likely to be obese as children living in the least deprived areas (adjustments made for age sex and ethnicity)

- The child obesity rate has decreased since 2018/19, and while this has decreased since last year, it is too early to report a trend.

Health risks and possible treatment options

The prevalence of obesity is increasing and poses severe health implications as a result of additional complications that can arise from increased levels of adipose(fat) tissue, such as (but not limited to):

- diabetes

- cancers

- high blood cholesterol

- heart disease

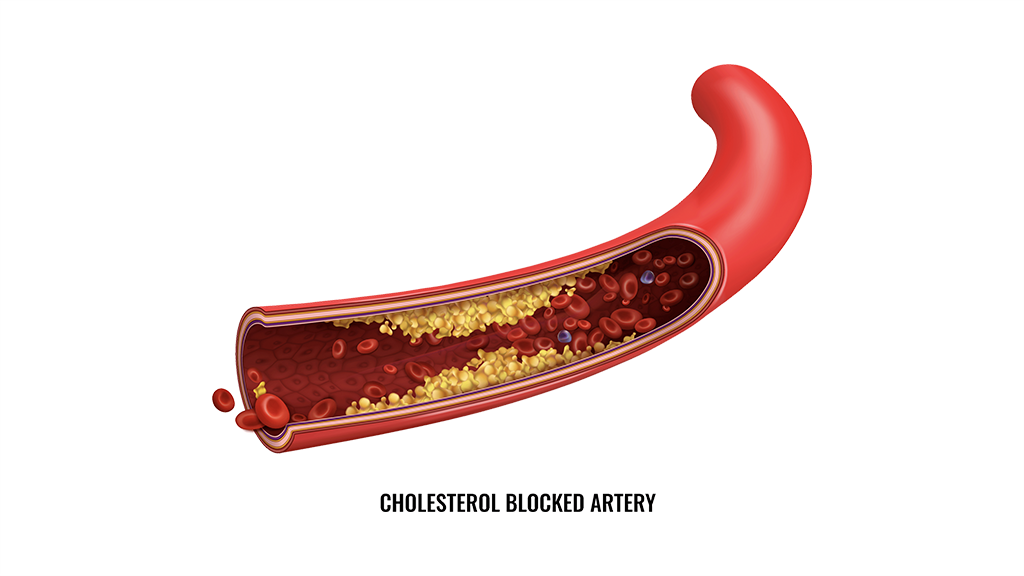

- atherosclerosis

- high blood pressure

- sleep disorders

- death.

Treatment options for obesity will vary per individual, they will depend on the overall cause and gravity of the condition along with considerations such as potential complications typically requiring a specialised plan of action. Some examples of possible treatment include:

- Developing a healthy eating plan

- Increasing physical activity

- Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved weight-loss medicines

- Weight loss surgery.

The most traditional initial form of weight loss is a balanced diet which contains foods from each of the five food groups, with a combination of regular exercise. However, it is important to realise that not all cases are simple or straightforward, particularly if an individual presents with additional health concerns. It is suggested for individuals to continue to maintain a healthy diet with exercise when applying any alternative methods or treatments to ensure their overall wellbeing is being maintained.

As obesity can affect not only an individual's physical wellbeing but also their mental wellbeing, social and emotional health such as the way individuals act or perceive themselves and how they interact, or don’t, with others. It is important to handle any conversations around this topic with care, kindness and respect. Should you feel that you are not comfortable to discuss such matters or are unsure how to guide an individual, remember to refer, point your client in the direction of a professional who can help them, should they be open to this idea and seek help. You are not there to diagnose, only discuss health matters and offer guidance, not to force an individual to do something they do not wish to do.

How is obesity measured?

Excessive body fat is defined as the volume of body fat that exceeds essential body fat plus reserve body Fat. Measuring excessive body fat can be challenging, as there may be variances with the reliability of certain measurements such as:

- Body girth

- Skin Fold

- Bioimpedance

- Hydrostatic weighing

- Waist to hip ratio

- Body Mass Index (BMI)

- Crude measure

- Weight (kg) / height (m2)

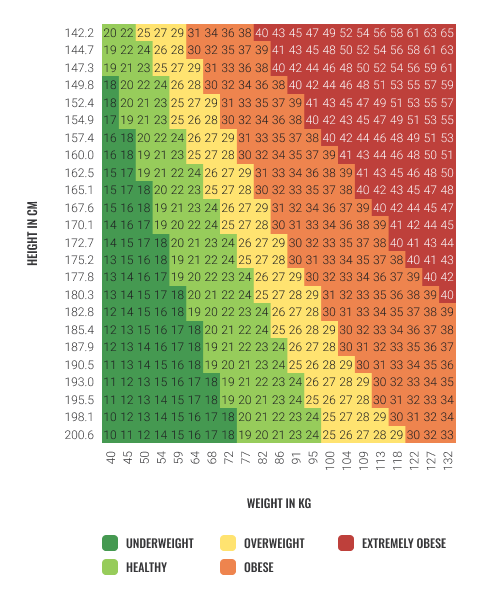

Both medical and health professionals typically, initially measure both body mass index (BMI) and waist circumference to monitor and diagnose if a patient is overweight or obese. These, however, are crude measurements as they do not take into account other body tissue types such as muscle tissue. For example, someone with high muscle mass, such as Arnold Schwarzenegger would likely present as obese when we know this is certainly not the case! Therefore, BMI, along with waist to hip ratio, should generally be used more as a guide than a conclusive diagnostic tool.

BMI is determined by using the following calculation: BMI = Weight (Kg) ÷ Height (m2)

For example, if an individual weighs 55Kg and is 163 cm tall, the calculation would look like:

= 55 ÷ 2.66

= 20.6

BMI = 21

The next step would then be to cross-check this figure against a chart such as the following to provide a rough guide to determine if an individual’s weight is at an appropriate range based on their height. For the individual above, with a BMI of 21, they would fall into the healthy range.

Typically, many people will assume that an obese person must simply have poor dietary habits. As we now know the issue of obesity is much more complex as there are many influencing factors such as environmental, genetics and underlying medical conditions. Several theories have attempted to explain the causes of obesity. Some of these theories include:

- Energy balance theory

- Fat cell theory

- Set point theory

- Insulin theory

- Dietary fat theory

- Genetic theory

Let us look at each of these in more detail.

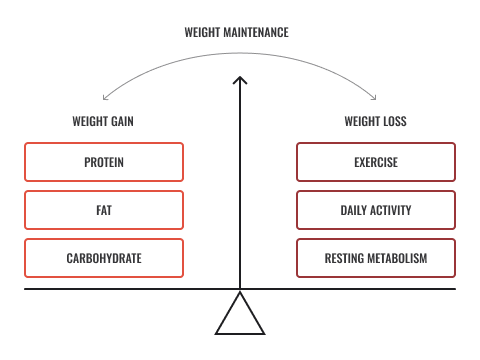

Energy balance theory

The energy balance theory refers to the balance between energy in versus energy out and the overall effect on body weight. For example, when an individual consumes the same amount of energy (calories) as they burn, their body weight should remain relatively stable, i.e. no significant changes in weight loss or weight gain. To achieve weight loss, this theory states this would require the volume of energy in to be less than the energy out, therefore, the individual burns more calories than they consume. Conversely, weight gain would occur when the volume of energy in, is greater than the volume of energy out, more calories being consumed than burnt.

In the following video, the European Food Information Council explains energy balance with some good examples of how to keep energy balance at a healthy level.

The fat cell theory

The fat cell theory states that individuals inherit the extra fat cells from birth, or with the genetic structure to develop additional fat cells during childhood and adolescence. This is referred to as hyperplasia; the enlargement of an organ or tissue caused by an increase in the reproduction rate of its cells. Once formed, these fat cells cannot be lost by diet or exercise, with studies indicating that weight reduction efforts may cause a reduction in its size, but not in number

The body can increase its fat storage in two ways:

- An increase in the number of fat cells (hyperplasia)

- An increase in the volume of fat in pre-existing fat cells.

Research indicates that the number of fat cells increases and maybe the difference between obese and non-obese (Powers and Howley 2000). Children who gain a large number of fat cells may be predisposed to obesity.

The set point theory

Each human body has a pre-set baseline hardwired into our genetic material; this is known as the “set point”. This correlates with homeostasis, the body's inbuilt mechanism to maintain the balance of the internal bodily environment, which is in a constant challenge with its external environment. For example, when the body is in a cold environment, it will shiver to produce heat, or conversely, when it is in a warm environment, the body produces sweat in an attempt to cool the body and bring it as close to normal body temperature as possible, to ensure the internal organs are in an optimal environment so they can function effectively.

The same process applies to bodyweight with the natural weight range also referred to as the “set point”. The set point acts as a thermostat, aiming to maintain a particular level of body fat, essentially dictating how much fat a person should carry (Powers and Howley 2000).

In regards to fat cells and their storage, in times of food shortage, the body may act to protect itself by increasing fat storage for the individual in the event that fat should be required for survival. If fat levels fall below the currently recognised, the body can detect this and act to return fat levels towards set point by transmitting signals, or ‘hunger pangs’, and also reducing the speed of the metabolism in an attempt to bring the weight back to the pre-recognised set point.

The set point theory research suggests the body and brain are in a battle to regain the set point weight. From this, we can gather that it would be more effective to carry out regular, minor, sustainable modifications to weight rather than a sudden and strict calorie limitation with large energy burn from exercise. This is why, reality television shows that incorporate intense training and diet modifications, which whilst producing signs of weight loss in the participants, often have a track record of the participants returning to their initial weight very quickly after the show and intense training has ended. Why? Because the body will act to return to what it knows, or what it has known for a while, where it feels comfortable. With this in mind, exercising moderately and eating a nutritional and balanced diet will assist in maintaining a natural weight loss pattern or maintenance of the desired weight.

The following video, a TedTalk conducted by neuroscientist Sandra Aamodt, explains why dieting isn’t always effective. This video is slightly lengthy; however, it is packed with lots of useful information which you can share with your clients.

Insulin theory

The insulin theory, also known as the carbohydrate-insulin model of obesity (CIM) proposes that the consumption of high glycaemic food promotes the laying down fat ( adipose) tissue via the stimulation of the hormone insulin, along with decreasing energy expenditure and metabolic rate. The boost in insulin levels is ( or was) thought to be the main cause of obesity, which leads to hunger, increased fat uptake, and a decrease in energy expenditure. However, these days, research is highlighting that the insulin theory does not apply independently of other factors such as energy balance and its correlation to metabolism requires further research. If the insulin theory was to play such a big role in weight gain, then those who ate high volumes of high glycaemic foods such as rice, for example, which seen often in Asian countries, there should be, by default, a large percentage of obese individuals in these countries as a result of their diet. We know, however, that this is not the case which therefore shows that the insulin theory requires further research in regards to an accurate understanding on the role of high glycaemic foods, particularly in regards to their effect on metabolism and energy expenditure. It can be said, however, that it is indeed clear that insulin does play a vital role in increased levels of fat tissue. With this in mind, it is important to be aware that any drug, diet, or other factors that cause an increase in insulin levels can trigger obesity.

Dietary fat theory

Obesity has been concisely related to an imbalance of energy in versus the energy expelled, i.e. more energy in ( consumed) than the energy expelled through physical activity or exercise) resulting in a weight gain. Research has long since identified that obesity and becoming overweight results from, not simply the volume of food consumed but more importantly the type of foods consumed with dietary fat playing the biggest role in weight gain - “You are what you eat?”

The genetic theory

There are two Genetic Theory Strands:

1. Obesity gene passed from parent to child (i.e. ‘Thrifty’ genotype)

As suggested by the Fat Cell theory, individuals inherit the extra fat cells from birth or are genetically predisposed to develop additional fat cells during childhood and adolescence. The thrifty genotype theory is based on an individual possessing a gene which enables them to efficiently accumulate and breakdown foods to deposit fat through periods where food is in abundance to then be able to provide the body during a period of food shortage, i.e. feast or famine. This is genotype is of benefit for child-bearing woman, enabling them to fatten during periods of food abundance and therefor having nutrients and energy available for child development and maintenance of their energy systems. This would also be suitable for our hunter-gatherer ancestors, preparing them for periods of food shortages however these days, in our modern society, famine is an event which rarely occurs therefor the Thrifty genotype prepares an individual for an event which does not occur, and instead, as a result, more often achieving a mismatch between energy consumption and energy output, giving rise to increasing obesity levels and occurrences of chronic illnesses such as cardiovascular disease and diabetes as a result of additional adipose tissue.

2. Dietary and exercise lifestyle habits passed on from parent to child

Eating behaviours are typically developed during the early years of life through parental influences. These form habits relating to their food choices that impact their wellbeing and are often passed down to their offspring and can have a big impact on future behaviours and food choices. Parents and caregivers can have a strong influence over children’s food choices, as they have greater control over children’s actions during this age range, with outside influences usually being of less significance than the actions of their immediate family. Through education and learning, children will pick up new ideas and understanding surrounding eating and make slight modifications however once a certain structure and behaviour have been developed, it is difficult and can take some time to adapt to a new set of ways.

Physical activity is defined as doing at least 30 minutes of brisk walking or moderate-intensity physical activity (or equivalent vigorous activity), for at least 10 minutes at a time, at least five days a week.NZ Ministry of Health

Physical activity refers to performing activities that raise the heart rate above resting, the feeling of being “huffy puffy”. It doesn’t have to be a gym work out; physical activity levels can be achieved by doing activities such as:

- Walking

- Dancing

- Housework

- A physical job

- Sitting less in a sedentary role

- Active transport - such as walking to the shops, cycling to work, getting off the bus a stop early to walk the remainder.

Exercise generally refers to a movement or routine which is planned, structured, intentional, and repetitive, done so with the purpose of either improving or maintaining fitness. For example, a strength training, flexibility, muscular endurance or cardiovascular fitness plan which is designed to be performed regularly for a particular period of time with the aid of improving levels for a goal.

MYTH - “In order to get fit or improve health you need to join a gym and train regularly.”

Small increases in physical activity levels have been shown to have provided many benefits to health, health conditions and general wellbeing via changes in blood pressure, lowering obesity levels, decreased prevalence of cardiovascular disease and its risk factors, improved mental health and many more.

The science behind moving more:

- Regular exercise strengthens the heart, causing it to pump more highly oxygenated blood with each beat

- Exercise may aid to control cigarette smoking, hypertension, lipid abnormalities, diabetes and emotional stress

- Evidence suggests that regular, moderate, or vigorous occupational or leisure-time physical activity may protect against coronary heart disease and might improve the likelihood of survival from a heart attack.

Whilst this list only represents a small example of the possible health benefits of moving more, these provide a small demonstration on not only the impacts to an individual’s health as a result of being physically inactive but also on the cost of medical illness. It is estimated that between 1,300 and 1,560 deaths could be prevented each year in New Zealand if the whole adult population became physically active. An increase in activity of only 5% of the population would save the country approximately $24 million per year!

There is a multitude of reasons people use to explain lack of inactivity, some are easy to overcome, some are little trickier. As a fitness professional, you can support your clients with ideas and design their program in a way in which they do not feel overwhelmed or over-committed before they begin in order to help them reduce some of their barriers with an aim of adhering to exercise or physical activity.

Some common reasons people link to the inability to exercise:

- Too tired to exercise

- Don’t have the time

- Don’t like to exercise on their own- don’t have a “gym buddy”

- Get bored easily

- Too embarrassed to exercise (feeling overweight, uncoordinated, unsure what to do in the gym)

- Unable to pay membership fees

- Family commitments (inc. partner or relative care)

- Mobility- unable to get to the gym or perhaps the gym venue is not accessible (disability access)

- Social activities- spending time with friends, travelling etc.

- Attitudes to regular physical activity- they have tried it before but unable to stick to a regular program.

- Culture as a barrier- some cultures prevent training with members of the opposite sex or avoid performing certain exercises, for example, within the Muslim culture, cycling is not widely permitted for women.

New Zealand activity levels

The New Zealand Health Survey 2018/19 reported:

- Around half of all adults (51%) are physically active for at least 30 minutes on 5 or more days per week

- Men are more likely (55%) than women (48%) to be physically active for at least 30 minutes on 5 or more days per week

- 1 in 7 (14%) adults are physically active for less than 30 minutes per week

- Pacific and Asian adults are less likely to be physically active than non-Pacific, non-Asian adults.

This data illustrates a sharp reduction in the participation levels in physical activity from the previous survey conducted in 2013/2014 by Sport New Zealand which reported

- Almost 7 in 10 (68%) adults took part in at least 1 activity on at least 3 days a week

- More than 1 in 3 (35%) took part in at least 1 activity on at least 5 days a week.

How does inactivity affect physical capacity?

Insufficient levels of activity can give rise to several knock-on effects to an individual’s physical and mental wellbeing. Click on each of the factors below to find out more of how a lack of physical activity can impact on each physiological aspect.

Aerobic capacity

Aerobic capacity is also known as cardiopulmonary capacity, cardiorespiratory fitness or VO2 max. The greater the aerobic capacity, the greater the body’s ability to continue to perform under vigorous activity for lengthier intervals. Insufficient physical activity has the following implications on an individual aerobic capacity.

- Substantial deconditioning of the heart and cardiovascular system

- Increased resting heart rate

- Decreased stroke volume

- Decreased cardiac output (Q)

- Decreased VO2 max.

Body composition

Body composition or tissue type distribution plays a huge role in maintaining health. A change in body composition as a result of being physically inactive can result in:

- a decrease in muscle size (atrophy)

- fewer calories burned at rest, due to a lower muscle mass

- a reduction in muscle fibre stimulation (neuromuscular)

- an increased body fat - placing organs under greater strain requiring them to work hard to perform their functions

- directly affecting performance: gaining as little as 4lbs in weight can decrease VO2 max by 3%.

Flexibility

A lack of moving or stretching can result in a rapid decrease in the range of movement which occurs around a joint, giving rise to the potential for muscular tissue shortening, tightening of ligaments and tendons. This can, in turn, lead to the decreased ability to perform everyday functions as a result of poor joint function.

Bone mass

Bone mass and bone density play a significant role in the prevention of conditions such as osteoporosis.

As a result of decreased levels of physical activity, bone mass decreases giving rise to increased risks to diseases such as osteoporosis as well as being more susceptible to breaks and fractures.

Speed

Though other aspects of muscular and aerobic fitness are impacted, research has shown that physical inactivity results in a loss however this loss is relatively small, typically this would align with de-training and deconditioning.

Strength

As a result of muscular atrophy, a decrease in muscle size occurs with decreased activity levels, this, in turn, results in decreasing muscular strength.

Power

Power = strength/time, the stronger the muscle and the faster it can contract, the greater the power achieved. With inactivity resulting in a decline in both muscular strength and speed, muscular power will decrease.

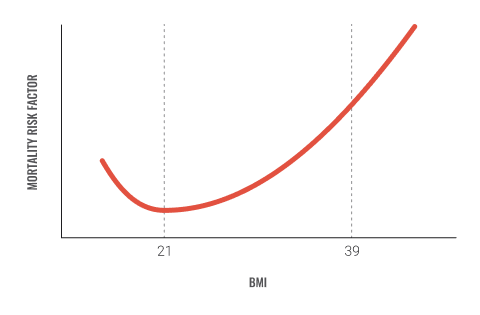

Physical inactivity as a risk factor

Research has demonstrated that an increase in physical activity was associated with a decrease in the risk of coronary heart disease. The level of physical inactivity predates the onset of coronary heart disease (CHD), implying that CHD can occur as a result of decreasing activity levels and increasing levels of excess fatty tissue. The following graph illustrates the exponential increase in mortality risk factors as BMI increases.

Sedentary people have about twice the chance of experiencing coronary heart disease. The risk is just as high in smokers, individuals with high blood pressure or high cholesterol.

The following statistics represent the impact of inactivity, smoking, and obesity on cardiovascular disease in New Zealand:

- 172,000 (1 in 20 adults) people in New Zealand are living with heart disease

- 33% of deaths are caused by cardiovascular disease annually.

- Cardiovascular disease is the leading cause of death in New Zealand (including stroke, heart and blood vessel disease)

- Every 90 minutes a New Zealander dies from heart disease

- An estimated 5,000 (around 12 per day) people die prematurely from smoking each year

- Cardiovascular disease is the number 1 killer of women globally

- Women who smoke are three times more likely to have a heart attack than women who do not smoke

- 2,920 women died in New Zealand in 2013, equating to 8 women a day or 55 each week

- Kiwi women and five times more likely to die from heart disease than breast cancer

- 31% of New Zealand adults (15 years or older) are obese, compared to 66% of Pacific adults and 47% of Māori adults

- 17% is the smoking rate for New Zealand adults compared to 38% for Māori adults and 24% for pacific adults

- You are 30% more likely to be physically active if you are a Pacific, Māori or Asian adults than non-Māori, non-Pacific or non-Asian

- 1 in 9 (11%) New Zealand children (aged 2-14 years) are obese.

What is cardiovascular disease

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is a term used to describe a range of disorders which affect the heart, its blood vessels and the related circulatory system. Click on each of the following examples to find out more:

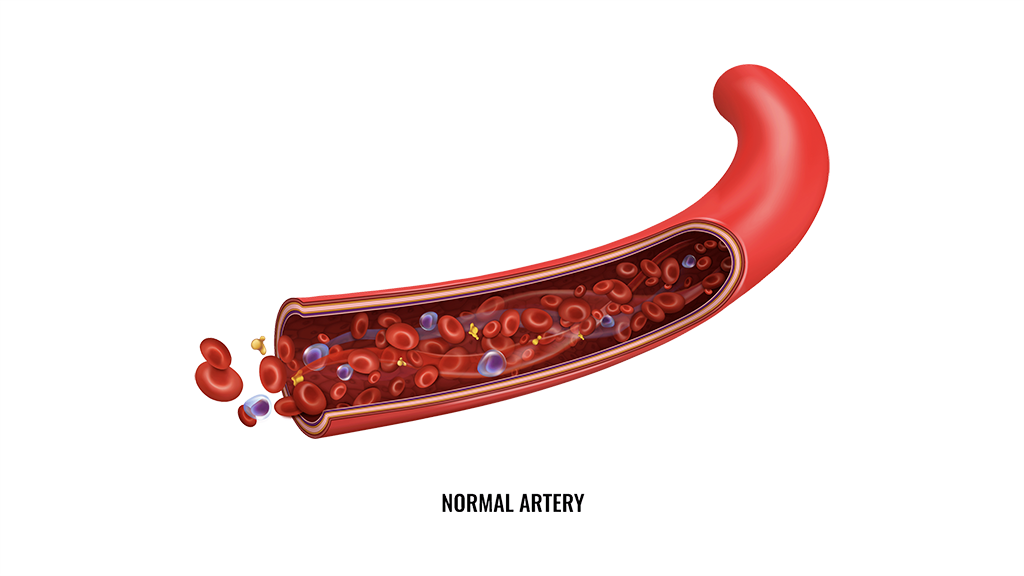

Commonly called “hardening of the arteries”, occurring as a result of the thickening of the walls of arteries of the heart and their loss of elasticity. The most frequent form is Atherosclerosis which more typically occurs mainly in middle-aged and/or elderly individuals and linked to eating foods with high-fat contents. In atherosclerosis, arteries become thickened by deposits of fat and other debris and, in turn, become less elastic. As a result, blood is prohibited from flowing smoothly thus making the blood more susceptible to forming clots. When a blood clot blocks or partially blocks one of the coronary arteries this is termed a coronary thrombosis – heart attack, should a clot form in an artery of the brain, this may produce a cerebral thrombosis – form of a stroke.

The American College of Sports Medicine (ACSM) recognises high blood pressure to be reflected in a reading of 140/90mmHg or higher. Blood pressure represents the force exerted against the walls of the arteries as the heart contracts (systolic) and relaxes (diastolic). When arteries become narrowed as found in atherosclerosis, the heart must pump harder to exert the same force, if this additional workload continues, the result is most typically reflected via hypertension/high blood pressure. This condition can also further enhance the likelihood of an aneurysm occurring, which is an abnormal dilation/out pocketing of a major artery, as such hypertension is often termed the “silent killer” as there are no signs or symptoms. Good news, however, is exercise can help! Evidence demonstrates decreases in both systolic and diastolic by 6 – 7 mmHg can be achieved as a result of maintaining regular moderate physical activity with higher intensity exercising likely to produce a greater decrease in systolic blood pressure. It is vital, however, to ensure that exercise is planned and programmed for patients suffering from hypertension in collaboration with their G.P and other allied health professionals as there are several exercises which should be adapted and avoided in order to ensure a safe and healthy training regime.

A heart attack, also known as a myocardial infarction, occurs when the coronary arteries are unable to supply the heart with adequate blood supply (ischemia) and can occur as a result of many of the cardiovascular disorders. The most common disorders of the heart relating to a heart attack are coronary artery disease (CHD) or ischemic heart disease, as seen in the advanced stages of atherosclerosis. During and as a result of a heart attack, a person’s health is at serious risk as when heart muscle cells are deprived of oxygen, they die.

Chest pain occurs when restricted blood flow to the heart occurs and is a consequence of coronary heart disease (CHD). Chest pains can arise during periods of stress, emotional upset, physical exertion

Also known as heart arrhythmias indicates a disturbance in the normal rhythm of the heart. This can occur when the electrical impulses that coordinate your heartbeats are not functioning properly, causing the heart to beat too fast, too slow, or irregularly. Disturbances in the regular heart rhythm can lead to blood clots, heart palpitations, heart attacks and strokes.

A stroke occurs as a result of damage to arteries which supply blood to the brain. This blockage of the cerebral arteries can cause cell death in the cells of the brain. If many are damaged/destroyed the result may be partial paralysis, speech impairment or death.

Occurs when the heart muscle becomes damaged because of a heart attack. A damaged heart muscle lacks the contractive force to circulate blood properly. As a result, there is a decrease in both the pressure and rate of circulating blood, this causes the blood returning to the heart to “back up”, producing congestion or swelling which is referred to as oedema. The back up of blood can also cause pressure to build up and cause congestion in the main vein that serves the kidneys, causing a decreased oxygen supply (oxygen is transported in the blood) decreasing the kidney's ability to perform optimally, therefore, reducing their ability to excrete water and sodium.

Involves damage to one or more of the four small heart valves following an episode or reoccurring episodes of acute rheumatic fever (ARF), resulting in lasting damage to the heart. Acute rheumatoid fever is an illness which occurs as an autoimmune response to an infection caused by the Streptococcus A bacteria.

Congenital heart defects (CHDs) are one of the most common types of birth defect. CHDs are abnormalities in the development of the heart and its blood vessels. These abnormalities develop before birth and can vary from mild (a small hole in the heart) to serious (poorly formed structural components of the heart). Most congenital heart defects have no know causes.

Risk factors for coronary heart disease

There is no known singular cause of any heart conditions, however, there are many factors which increases the likelihood of developing one. Some of these factors are out with our control such as age, gender and genetic hereditary, however many are within our control such as

- Smoking

- High blood pressure

- Physical inactivity

- Obesity

- Stress

- Diabetes

- High Low-Density Lipoprotein (LDL) - cholesterol

These are all easily modifiable risk factors which by making just a few positive changes, could be adding years to life! It is never too early or too late to start modelling behaviours which promote a healthy heart!

In order to maintain a healthy weight, it is recommended to take part in at least two and a half hours of physical activity per week. This works out to be around 30 minutes of moderate activity most days of the week such as brisk walking, swimming, or household tasks like mowing the lawn. A healthy 24-hours includes:

- Quality uninterrupted sleep of 9 to 11 hours per night for those aged 5 to 13 years, and 8 to 10 hours per night for those aged 14 to 17 years, with consistent bed and wake-up times

- An accumulation of at least 1 hour a day of moderate to vigorous physical activity (incorporate vigorous physical activities and activities that strengthen muscles and bones, at least 3 days a week)

- No more than 2 hours per day of recreational screen time.

For the remainder of the day, individuals should participate in structured and unstructured light physical activities. It is important to break up sitting time by getting up to move throughout the day so that sitting is not done for long periods of time.

Programming considerations

In regard to programming for obese clients, always edge on the side of caution and use the pre-screening questionnaire to establish their eligibility for exercise and any risk factors which could be a contra or absolute indicators and require medical clearance. Should they be a client of other allied health professionals, ensure you consult with them to make sure your treatments align and that both parties are aware of the proposed exercise regime.

When designing an exercise program and general recommendations to promote safe and effective weight loss through exercise, consider the following:

-

Type of exercise: Is it safe to perform, will it exacerbate any induce any symptoms or acute responses?

-

Duration of exercise: Is it long enough to activate the relevant body system, is it suitable in length to be safe?

-

The intensity of exercise: Is it pitched at the correct level of intensity to initiate the desired muscular response without over stimulating the client?

-

Frequency of exercise: How often should they perform this exercise to stimulate fat burn and remain with safe training parameters for their condition?

-

Self-monitoring of exercise: Does the client know how to perform the exercise independently safely and effectively, should they repeat these independently outwith the planned sessions?

-

Instructor monitoring of exercise: Are you confident enough in the exercise, its requirements around safety and suitable adaptations relating to the client’s ability or condition?

In this topic, we focused on obesity, its relation to cardiovascular disease and the significance of the physical activity. You learnt about:

- Obesity and its contributing factors

- Theories of obesity

- Physical activity and its benefits

- Obesity and cardiovascular disease

- Health and exercise recommendations.