When responding to an animal in need of first aid, a calm and structured approach is essential. Assessing the situation allows you to understand the urgency, identify potential hazards, and develop a clear plan of action.

Evaluate the Environment |

Start by observing the surroundings to identify any immediate risks to yourself or the animal. Look for potential hazards such as dangerous objects, other animals, or environmental factors that could escalate the situation. Ensure that you have a safe path to approach and retreat if necessary. |

Observe the Animal’s Condition |

Assess the animal’s physical state and behaviour. Look for visible injuries, signs of distress, or abnormal behaviour that could indicate pain or fear. Common signs to assess include:

|

Assess the Level of Urgency |

Determine if the injury or illness requires immediate intervention or if you can take time to carefully apply basic first aid. For example, severe bleeding, difficulty breathing, or unresponsiveness are urgent and require rapid action. |

Plan and Prepare for First Aid |

Based on your assessment, decide on the first aid techniques you’ll use and gather any necessary supplies, such as bandages, antiseptics, or gloves from the first aid kit. Enlist the help of another team member if available to assist or restrain the animal safely. |

Approach with Caution |

When ready, approach the animal calmly, speaking in a soothing voice to minimise stress. Remember that an injured or frightened animal may react defensively, so remain alert and prepared to step back if needed. |

Now that you have had a quick overview of assessing the situation and what it entails let's explore this in more depth throughout this module.

Before you learn how to provide basic animal first aid, it is important to remember the basic principles of animal welfare and ethics.

Animal ethics

Ethical management and handling of animals are critical to the animal care industry.

As an animal carer, it is your responsibility to behave ethically when working with animals. You can think about ethical behaviours as ‘doing the right thing’ or ‘doing what is best’ for the animal.

You can be confident that you are upholding animal ethics if you follow the principles of animal welfare.

Principles of animal welfare

There are eight key principles of animal welfare.

- Animals should not suffer from prolonged hunger

- Animals should not suffer from prolonged thirst

- Animals should have a comfortable environment

- Animals should have enough space to be able to move around freely

- Animals should be free of physical injuries

- Animals should be free of disease

- Animals should not suffer pain, fear or stress

- Animals should be able to express normal, non-harmful, social behaviours

Upholding animal ethics when providing essential first aid to animals

In this module, your focus is on providing essential first aid to animals. You will learn how to provide an initial response where first aid is required. You will learn how to:

- assess circumstances and plan your response

- approach, secure and protect animals

- provide first aid assistance to animals.

Reading

Check out the following links relating to animal welfare standards and principles.

The following table summarises the principles relevant to this module and how you can uphold them in the workplace when you provide basic animal first aid.

| Principle | The animal should have access to: | As an animal first aider, you should: |

|---|---|---|

| Animals should be free of physical injuries |

|

|

| Animals should not suffer pain, fear or stress |

|

|

Case Study

At Happy Paws, it’s time for the monthly team meeting, and today’s focus is a critical discussion on animal ethics and the 8 principles of animal welfare. The meeting includes animal attendants, veterinary staff, management, and enrichment specialists who gather in the break room, where their supervisor, Jess, begins the session.

Introduction and Purpose |

|

Jess starts by emphasising that, as Happy Paws grows, maintaining high ethical standards in animal care is essential. She explains that the meeting’s goal is to reinforce the team’s commitment to the welfare of all animals in their care, especially since Happy Paws hosts a variety of species, each with unique needs. She continues, “Animal welfare isn’t just about providing food, water, and shelter—it’s about addressing their physical, mental, and emotional needs. Let’s use the 8 principles of animal welfare as our framework to ensure we’re meeting these needs.” |

The 8 Principles of Animal Welfare Discussion |

|

Jess then presents each principle, encouraging open discussion on how they apply at Happy Paws and inviting team members to share experiences or raise concerns.

|

Action Plan |

|

To wrap up, Jess summarises action points:

The team leaves the meeting feeling more connected to Happy Paws' commitment to ethical, compassionate animal care and confident in their ability to uphold the 8 principles of animal welfare. |

Recognising an emergency situation

In this topic, we will be studying emergencies in the context of providing animal first aid.

We can define an emergency as a situation where there is an immediate risk to the health and life of an animal. An emergency situation requires immediate intervention to prevent deterioration.

A medical emergency is a situation that requires immediate veterinary attention or first aid:

- to stabilise the animal (prevent death)

- protect any injuries from further harm

- increase the likelihood of survival until veterinary intervention.

Emergencies often occur without warning, such as a cat attacking a rabbit. Others, although just as serious, are not as easy to see. “For example, a German Shepherd appears restless after a large meal and tries to vomit; unknown to the owner, this is the beginning of gastric dilatation and volvulus (GDV), one of the most serious medical emergencies in dogs” (Williams, Llera & Ward n.d.).

You will need to know how to recognise emergencies when:

- taking phone calls

- a client arrives with an ill or injured animal

- communicating with staff

- in the field (places that are not in an animal medical clinic).

In the case of emergencies, an animal care workplace should establish procedures and practices to facilitate the speedy assessment of animal incidents. They should be set up to give an immediate first aid response or advise owners on how to carry out their own effective first aid. Make sure you know which veterinary clinic, wildlife rescue centre or other entity you will contact for support, and which facilities are available for emergencies during normal work hours and after hours.

Watch

The next video explains what an emergency is.

Classifying emergencies

It is essential when working in the animal care industry that you can recognise when a situation is an emergency because it will help determine your actions when providing first aid. Situations requiring first aid can be classified into one of four types:

- Life-threatening emergencies require immediate attention. The animal is at risk of dying or deteriorating significantly if not seen by a veterinarian within 1-60 minutes.

- Intermediate emergencies require immediate attention but are not imminently life-threatening. The animal needs to be seen by a veterinarian in the next 30 minutes to 2 hours.

- Minor emergencies do not require immediate veterinary attention. However, the animal needs to be seen that day, preferably sooner rather than later.

- Non-emergencies can usually be treated with just basic first aid and do not require a veterinarian’s attention unless the animal’s condition significantly deteriorates.

All other medical situations are considered routine care. Routine care is planned and therefore does not require first aid. The following table lists some examples of situations and symptoms that could be classified as the four different levels of emergency as well as some common routine care procedures.

| Classification | Situation and symptoms |

|---|---|

| Life-threatening emergency |

Snake bite * |

| Immediate attention – intermediate emergency |

Tick paralysis * |

| Minor emergency |

Small cuts |

| Non-emergency |

Catfight abscess |

| Routine care |

Vaccination |

First aid management principles and rules

Life-threatening, intermediate and minor emergencies all require first aid. The aims of first aid are to stop the animal from deteriorating, to promote recovery and to preserve life. It is not to treat the animal. First aid should be administered, and the animal should be suitably restrained and then transported to the nearest open veterinary facility so that they may fully treat the emergency condition.

First aid is not a substitute for veterinary care. Any first aid should be immediately followed up with veterinary care. Stay safe and do no harm.atDove, 2020

What is animal first aid?

”First aid refers to medical attention that is usually administered immediately after the injury occurs and at the location where it occurred. It often consists of a one-time, short-term treatment and requires little technology or training to administer” (Occupational Safety & Health Administration n.d.).

Animal first aid is based on the principles of medicine and surgery. The main purpose is to alleviate unnecessary suffering of the animal and give them the best chance of survival until a veterinarian is able to attend the animal.

In an emergency, when no veterinarian is immediately available to treat the animal, a first aider, such as an untrained person, veterinary nurse or animal carer, may administer first aid treatment to animals as an interim measure. Aim to be prepared. Obtain the necessary skills to act quickly and suitably. Providing first aid “bridges the gap between ‘first response’ and ‘professional care’” (Philpott n.d.).

First aid skills will be invaluable when working in your animal care workplace, giving you the confidence to deal with incidents that may come your way (AAWS 2014).

Aims, principles and rules of first aid

The aims of first aid are to:

- Preserve life

- Prevent suffering

- Prevent the situation from deteriorating.

The seven principles of first aid are to:

- Preserve life

- Prevent deterioration

- Promote recovery

- Take immediate action

- Calm the situation down

- Call for medical assistance

- Apply the relevant treatment.

The rules of first aid are to:

- Keep calm

- Maintain the airway

- Control the hemorrhage

- Seek assistance if required.

Knowledge check 1

Watch

The next couple of videos are some examples of animal care emergency rooms and what their jobs entail.

When you are responsible for looking after an animal, you must protect their welfare. This is your duty of care. However, you also have a duty of care to protect yourself and any other people or animals in the area.

When attending to an animal emergency, your first priority is to make sure that no one else becomes a casualty. So, before you assess the animal and plan your first aid procedures, you must first secure the scene. Check the immediate surroundings for any signs of risks or dangers. Control or remove the dangers, but only if it is safe to - thereby avoiding further risk to the animal or yourself. To secure the scene:

- Assess the situation. Look for potential dangers to yourself, the injured animal, other people (including staff, clients, the general public) and other animals.

- Where possible, minimise the risks, but make sure your actions do not put yourself or anyone else at further risk.

- Now that you are sure there is no danger, you can triage the animal. Assess its condition and what it may require. Don’t move the animal except if it is in a life-threatening position, such as on a road and at risk of being hit by a car.

- If needed call for veterinary or wildlife emergency assistance. They can advise you if you are in doubt as to what to do.

- Apply first aid.

- If needed, transport directly to veterinary or wildlife assistance.

The specific potential hazards and risks will vary depending on the situation. If you are unsure the scene is appropriately secured, seek assistance or advice.

In the table below, here are some potential situations that may occur and steps you can take to secure the scene.

Situation |

Steps to secure the scene |

|---|---|

| 1. Dog injured by broken glass in a park | 1. Clear nearby glass or other sharp objects. 2. Keep other dogs and people at a distance. 3. Approach the dog calmly, observing for signs of pain or aggression. 4. Use a leash or muzzle if needed for restraint. |

| 2. Horse with a suspected leg injury in a paddock | 1. Clear the area of other horses. 2. Close the gate to prevent escape. 3. Approach the horse slowly, speaking softly. 4. Keep bystanders back to minimise stress. |

| 3. A cat found limping near a busy street |

2. Use a towel or blanket to restrain if necessary. 3. Monitor traffic, keeping a lookout for vehicles. 4. Calmly examine for injuries while reassuring the cat. |

| 4. A bird was injured on the ground in a public park | 1. Move people and other animals away to reduce stress. 2. Approach slowly and avoid sudden movements. 3. Gently place the bird in a secure box or carrier. 4. Minimise noise and activity near the bird. |

| 5. Dog attacked by another animal in a backyard | 1. Ensure the other animal is secured away. 2. Approach slowly to avoid startling the injured dog. 3. Use a muzzle or leash for restraint if needed. 4. Keep other pets and people away to reduce stress. |

| 6. Snake found with an injury on a hiking trail | 1. Clear the area of people and pets. 2. Avoid sudden movements and remain calm. 3. If experienced, use a snake-handling tool to secure the snake. 4. Call a trained handler or wildlife rescuer if necessary. |

| 7. Rabbit caught in garden netting | 1. Carefully cut away the netting to free the rabbit. 2. Move other pets and people away from the scene. 3. Use a towel to wrap and secure the rabbit to reduce movement. 4. Handle gently to avoid causing additional stress. |

| 8. A horse with a head wound in a stable | 1. Ensure the horse is in a stable area with no escape routes. 2. Approach calmly, staying out of the horse’s blind spots. 3. Use a halter and lead if needed for gentle control. 4. Minimise noise to keep the horse calm. |

| 9. Dog injured by barbed wire in a paddock | 1. Remove any nearby barbed wire or sharp objects. 2. Approach cautiously and avoid touching the wound area. 3. Use a muzzle if the dog shows signs of aggression. 4. Keep other animals and bystanders back for safety. |

| 10. Cat injured in an indoor household environment | 1. Secure other pets in a separate room. 2. Remove any dangerous items (e.g., sharp objects, small furniture). 3. Approach the cat slowly, watching for signs of distress. 4. Use a towel to gently wrap and secure if needed for examination. |

Case Study

While hiking on a popular nature trail, an animal care attendant named Sam notices a dog limping and bleeding from one of its paws. The dog’s owner is nearby, looking distressed and unsure of what to do. Other hikers and pets are passing by, and the dog appears to be in pain and a bit defensive. Sam needs to secure the scene before administering first aid.

Steps to Secure the Scene |

|---|

|

Assess the Area for Immediate Hazards

|

|

Clear the Immediate Area

|

|

Approach the Dog Calmly and Slowly

|

|

Use Proper Restraint for Safety

|

|

Prepare First Aid Supplies

|

|

Minimise Noise and Distractions

|

|

Plan for Follow-up Care

|

By securing the scene, Sam creates a safe, controlled environment, making it possible to assess and begin first aid effectively. This approach minimises the risk of further injury to both the dog and the people involved.

Stressed and injured animals

When animals are sick or injured or visiting your animal care facility, they will be under some level of stress. Stress can lead to aggressive and defensive behaviour. Always evaluate the risks to both yourself, others and the animal before approaching or handling a sick or injured animal.

Animals have five basic reactions to stress or threat – the five ‘Fs’.

The five ‘Fs’ are:

- Fight

- Flight

- Freeze

- Faint

- Fidget (or fooling around).

When an animal is distressed and in pain, they, just like humans, can act in ways they otherwise would not. When this happens, they may:

- further injure themselves

- heighten their anxiety levels

- become aggressive.

Animal temperaments

An animal’s temperament is its individual “personality, makeup, disposition, or nature” (American Kennel Club n.d.). In other words, how an animal usually behaves is determined by its temperament. Animals can react negatively to a hesitant or inexperienced handler because the animal may interpret this fear or hesitancy as aggressive behaviour. Occasionally another worker or the owner of the animal may be required to calm the animal to enable animal handling, examination and treatment.

People must know their limitations around animals and work within these limits to avoid injury. Through understanding animal temperament and behaviour, the risk of injury can be reduced. Animals can bite, scratch or give a swift, hard kick. So, observe them carefully at times and respect their size and strength. Where possible, don't stand behind them (Workplace Health and Safety Queensland 2018).

Animals must be handled carefully as their behaviour is not always predictable. There is no simple risk control that will eliminate hazards completely. However, you can avoid incidents with animals by assessing the animal prior to handling and having a discussion, if possible, with its owner about its temperament and the likelihood of the animal becoming aggressive.

Examine the following range of dog temperaments and the related behaviours.

- Sound temperament: Confident, relaxed and self-assertive.

- Unsound temperament: Not calm, confident or self-assertive and displays fearful behaviour.

- Shy temperament: Afraid of unfamiliar people, places and things.

- Sharp temperament: Reacts immediately to individual environmental stimuli without thought.

- Submissive temperament: Surrenders authority and control to its leader.

- Sharp-shy temperament: Displays aggression based on fear.

- Temperamental temperament: Cannot cope with environmental stress.

- Hyperactive temperament: Moving fast constantly.

- Over-aggressive temperament: Reacts with more aggression than the situation warrants such as lunging, snarling, hissing, biting, and scratching.

- Frightened temperament: This could present as freeze, flight, fight, faint or fidget.

Potential risks to yourself and other people

The first concern is for the safety of the [first aider].Linklater A., 2020

When providing first aid, there are several hazards you should consider that pose a risk to you, as the first aider, as well as to other people that may be assisting or are simply present in the general area.

The most common risks to yourself and other people include:

- bites, scratches and kicks

- envenomation

- zoonoses

- manual handling.

Bites, scratches and kicks

Animal behaviour is difficult to predict and may change without warning. There is always a risk of being bitten, scratched, kicked or harmed in other ways by the animal you are working with. However, while administering first aid, the potential risk is often higher because the animal is typically afraid, stressed and/or in pain. These conditions typically make even the most placid animal less receptive to handling.

All animals are capable of inflicting bites and scratches.

The size of the animal, its dentition and jaw strength are all factors affecting the severity of bite they can deliver. Even a small animal may bite or scratch through your skin. Larger animals, such as livestock or kangaroos, can also inflict impact injuries (crushing, bruising and fractures) by kicking you.

Minimise the risk of bites, scratches and kicks

To minimise the risk of the animal injuring you or other people:

- use appropriate restraint and handling techniques and following the facility’s policies and procedures

- learn and recognise ‘warning’ signs typical for different species of animal

- handle aggressive or potentially dangerous animals with assistance

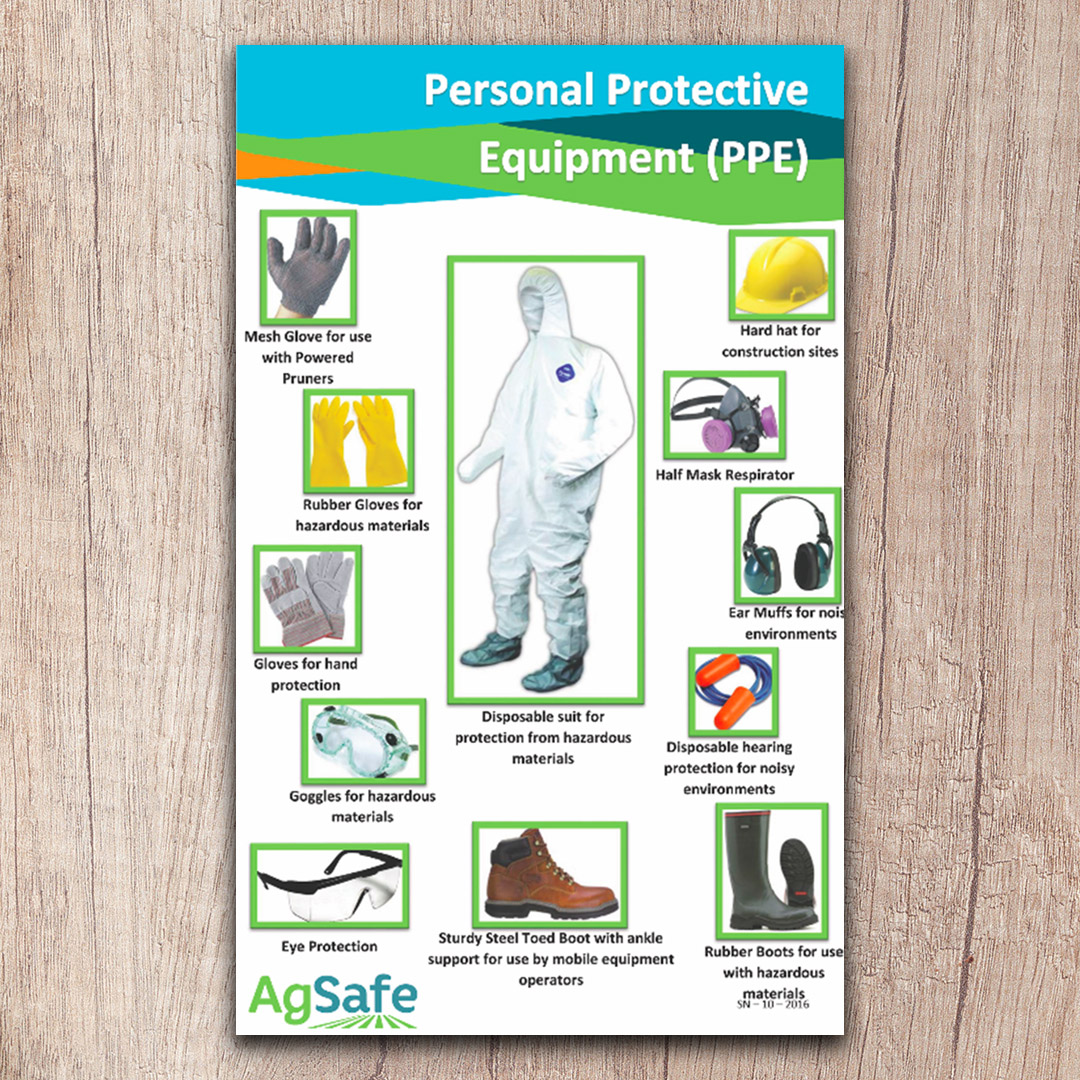

- wear appropriate PPE.

Anyone who is bitten or scratched may be exposed to biological hazards, which may be transmitted through saliva, secretions and blood of the animal that has bitten the person. If you are bitten or scratched, immediately wash with soap, preferably with an antiseptic soap, and running water. If the bite or scratch results in bleeding, immediately scrub the area for at least 15 minutes. After cleaning the area, apply a topical disinfectant and bandage to protect the wound. Depending on the severity of the injury, such as if you received a deep scratch or your foot is crushed by a large animal, seek medical treatment.

Some strategies to help you minimise your risk of bites, scratches and kicks can include:

| Assess the Animal's Behaviour |

Observe the animal’s body language for signs of stress, fear, or aggression, such as growling, pinned ears, bared teeth, or a defensive stance. |

|---|---|

| Approach Calmly and Confidently | Avoid sudden movements or loud noises that could startle the animal. Approach slowly and from the side, keeping your movements controlled and deliberate. |

| Use Proper Restraint Equipment | For animals prone to aggression, use muzzles, leashes, or harnesses, and ensure you’re trained in safe restraint techniques to reduce the risk of bites and scratches. |

| Wear Protective Clothing | Use appropriate protective gear such as gloves, long-sleeved clothing, and boots to minimise injuries from scratches or kicks. |

| Avoid Direct Eye Contact | Some animals perceive direct eye contact as a threat, so use a soft gaze and avoid staring directly at the animal. |

| Be Mindful of Personal Space | Maintain a safe distance and respect the animal’s personal space, especially with nervous or injured animals. Avoid reaching directly over the animal's head or back, as this can feel threatening to them. |

| Use Barriers if Needed | For particularly aggressive or unpredictable animals, use barriers like gates, partitions, or blankets to reduce the risk of contact during handling. |

| Stay Aware of Blind Spots | Larger animals like horses and cattle stay out of their blind spots, particularly behind them, as they may kick if startled. |

| Handle Animals Only When Necessary | If the animal is very aggressive or in extreme pain, consider whether handling is necessary or call for assistance from an experienced handler or veterinarian. |

| Enlist Help | For large or unpredictable animals, have an additional handler assist you in better controlling the situation and reducing stress on the animal. |

| Speak in a Calm, Soothing Voice | Use a quiet, reassuring tone to help calm the animal and establish trust, reducing the likelihood of aggressive reactions. |

| Monitor for Changes in Behaviour | Monitor any change in the animal’s behaviour or stress level, and adjust your approach accordingly to prevent escalation. |

Regardless of the severity of the injury, inform your supervisor.

Case Study

At Happy Paws Animal Care, Mia, an experienced animal care attendant, is called to help with an injured dog brought in after an accident. The dog, a medium-sized terrier mix named Max, has a deep cut on his leg and is visibly distressed, trembling and growling intermittently. Mia knows that even a normally friendly animal can act defensively when in pain, so she approaches cautiously to avoid potential bites, scratches, or kicks.

Situation and Response

- Assessing the Scene: Mia and her colleague, Sam, carefully observe Max from a slight distance, allowing him time to settle and become familiar with their presence. Mia gently speaks to him in a calming voice, helping to reassure him without causing further stress.

- Using Restraints for Safety: Before attempting to clean and bandage the wound, Mia uses a soft, adjustable muzzle designed to prevent biting but still allow Max to breathe comfortably. She asks Sam to gently hold Max’s head while she positions herself by his side to avoid kicks or sudden movement. Sam reassures Max with gentle petting on his neck, allowing Mia to clean his wound.

- Minimising Stress and Avoiding Injury: To prevent scratching or kicking, Mia moves slowly and calmly, keeping her hands clear of Max’s legs. She is careful to avoid any sudden movements that might startle him. Mia’s strategy includes taking short breaks to keep Max calm, ensuring that she can safely attend to his injury without escalating his stress.

Outcome

Mia and Sam work together, and they clean and dress Max’s wound successfully without incident. By following these steps to minimise risks, they ensure Max’s comfort and safety, protecting both themselves and the animal from potential harm.

This scenario highlights the importance of cautious handling, clear communication, and preventive measures like muzzling and positioning when working with animals in pain.

Envenomation

Envenomation is a risk in the animal care industry and occurs when a poisonous substance produced by an animal is injected into a person’s body by a bite, sting or penetrating wound.

Envenomation can be caused by snake or spider bites and marine animals. The type of envenomation will determine the specific treatment required.

Minimise the risk of envenomation

If the animal requiring first aid treatment is a venomous snake, your handling techniques and appropriate PPE are critical for your protection. If you are not confident handling snakes safely, ask for assistance.

If the animal requiring first ais is suspected of being bitten by a snake, make sure you check the immediate surroundings to ensure the snake has moved on or that is safely captured by an experienced snake catcher. Do not attempt to capture a wild snake yourself.

To minimise the risk of envenomation when working with venomous animals, such as snakes or spiders, it’s essential to follow specific safety protocols. Here are strategies to help reduce this risk:

| Learn Proper Handling Techniques | Ensure you’re trained in safe handling techniques specific to venomous species, including using appropriate tools and equipment. |

|---|---|

| Use Protective Gear | Wear personal protective equipment (PPE), such as long gloves, snake gaiters, and closed-toe boots, to reduce the chance of a bite. |

| Use Specialised Equipment | To handle venomous reptiles, use tools like snake hooks, tongs, and transparent shields to keep a safe distance between you and the animal. |

| Stay Calm and Avoid Sudden Movements | Venomous animals are often more reactive to quick movements. Move slowly and smoothly to avoid triggering defensive behaviours. |

| Avoid Handling When Not Necessary | Handle venomous animals only when essential, and limit physical contact as much as possible. Observe and work on them from a safe distance when feasible. |

| Know the Species and Its Behaviour | Familiarise yourself with the specific behaviours of the species you’re working with, including signs of agitation or aggression, to better anticipate their reactions. |

| Ensure Proper Housing and Enclosures | Use secure, escape-proof enclosures with proper ventilation, and always close and lock enclosures immediately after access. |

| Have a Clear Plan and Emergency Protocol | Know the first aid procedures and have emergency protocols in place for envenomation. Keep antivenom and a first aid kit accessible if appropriate. |

| Work in Pairs or With an Experienced Partner | Whenever possible, work with a trained colleague to assist and observe, providing immediate help if an incident occurs. |

| Maintain Situational Awareness | Always be aware of where the animal is and avoid distractions that could lead to mistakes. Stay focused and avoid turning your back on the animal. |

| Use Clear Signage | Label enclosures or areas where venomous animals are kept with clear signs to alert others and reduce accidental exposure. |

| Minimise Stress on the Animal | Stress can provoke venomous animals to strike. Keep handling to a minimum, and create a calm, low-stress environment to reduce defensive behaviours. |

| Keep a Safe Distance | Even smaller animals like spiders or scorpions use tools to handle and maintain a safe distance, as their strikes can be fast and unpredictable. |

| Regularly Inspect Equipment for Safety | Regularly check tools and enclosures to ensure they’re in good condition and can securely contain and handle venomous animals without failure. |

Treating snake bites

Australian venomous snakes produce venom that travels through the body in the lymphatic system rather than in the bloodstream. The fluid in the lymphatic system is pushed around the body by physical movement. If a person is bitten by a snake:

- Keep the person calm. Minimise their distress and movement.

- Do not wash the area of the bite or try to suck out the venom. It is extremely important to retain traces of venom for use with venom identification kits.

- Stop lymphatic spread. Do not use a tourniquet. Tourniquets can cause harmful restriction of blood flow. Instead, bandage the bite site firmly, splint and immobilise the whole limb. Ask the person to remain calm and as still as they can to minimise the movement of lymph around their body.

- Seek medical attention.

- Attend a hospital and receive antivenom.

Watch

Watch the following video (6:46 min) by St John WA, which demonstrates how to treat a snake bite.

Case Study

At Happy Paws Animal Care, the staff is trained to respond quickly and effectively to emergencies, including snake bites. One morning, a concerned owner rushes in with Charlie, a curious Labrador who was bitten on his leg while exploring the bushes.

Situation and Immediate Response |

|

Arrival and Triage: Securing the Animal and Scene: |

Treatment Procedure |

|

Applying Pressure Immobilisation: Administering Antivenom: Providing Supportive Care: |

Observation and Follow-Up |

|

Monitoring Recovery: Discharge and Aftercare: |

Key Takeaways |

| This case illustrates the essential steps in managing a snake bite, including immediate triage, pressure immobilisation, timely antivenom administration, and vigilant aftercare. The team’s knowledge, preparedness, and calm approach are instrumental in Charlie’s recovery, emphasising the importance of training and protocol adherence in emergency veterinary care. |

Zoonoses

Diseases that can spread from animals to humans are called zoonotic diseases or zoonoses. Pathogens (infectious, disease-causing agents) may be transmitted to humans directly from the animal via blood or other bodily substances during diagnostic or treatment procedures or indirectly from the animal’s environment.

It is important for you to understand that zoonoses may be contracted from both ill and apparently healthy animals.

Common zoonotic diseases in Australia include:

- Leptospirosis – a bacterial infection (Leptospira spp.) spread by contact with animal urine, such as infected dogs, pigs, cattle and rodents (NSW Health 2021).

- Psittacosis – a bacterial infection (Chlamydophila psittaci) transmitted by birds (NSW Health 2018).

- Q fever – a bacterial infection (Coxiella burnetiid) most commonly transmitted by cattle, sheep and goats (NSW Health 2019).

- Toxoplasmosis – a protozoan infection (Toxoplasma gondii) most commonly transmitted by cats in Australia. If infection occurs during pregnancy, it can cause “serious fetal disease” (Department of Health 2015).

Watch

Minimise the risk of zoonoses

Contamination by zoonoses can be preventable by taking several precautions, including:

- practising good personal and hand hygiene

- using appropriate disinfectants

- keeping immunisations up to date

- providing prompt and effective first aid treatment to cuts and scratches

- using personal protective equipment such as overalls, gloves, boots, goggles, scrub tops over your normal uniform and aprons

- following cleaning and disinfectant protocols

- following isolating processes with sick animals

- properly handling and storing food

- staff training on policies and procedures

- practice bite and scratch prevention

Manual handling

Manual handling covers a wide range of activities including:

- Lifting

- Pushing

- Pulling

- Holding

- Carrying

- Handling and restraining animals (Better Heath Channel 2017)

Tip

Minimise the risk of manual handling injuries

Your back is particularly at risk of manual handling injuries. Follow the specific manual handling procedures outlined by your workplace. To reduce the risk of manual handling injuries while providing first aid to animals:

- Lift and carry heavy animals correctly by keeping the animal close to your body and lifting with your thigh muscles.

- Never attempt to lift or carry animals by yourself if you think they are too heavy. Always ask for assistance to lift an animal over 20 kg, regardless of whether you think you can lift it by yourself.

- Use stretchers, lifting tables and other devices to assist you whenever they are available.

- Organise the immediate area to reduce the amount of bending, twisting and stretching required to pick up an animal.

- Take frequent breaks.

- Cool down after handling heavy animals with gentle, sustained stretches.

- Avoid awkward or twisting movement

- Improve your general fitness and strength.

- Warm up cold muscles with gentle stretches before lifting or carrying an animal (Better Heath Channel 2017).

- Maintain a safe distance from kick zones

- Avoiding overreaching

- Use supportive footwear

Manual Handing Fundermentals

Watch

The next couple of videos provide a demonstration of how to lift items correctly. The videos demonstrate using boxes, think of the boxes as animals.

Case Study

At Happy Paws Animal Care, Ellie, an experienced animal care attendant, and her colleague, Tom, are asked to help move Max, a large, elderly German Shepherd, onto an examination table. Max is experiencing joint pain and cannot get up on his own, requiring a careful, coordinated lift to avoid further injury to him or to the staff.

Scenario and Response

| Assessing the Situation | Before attempting to lift Max, Ellie and Tom discuss the best approach. They assess Max’s weight and condition, noting that lifting him alone could strain their backs and that teamwork will be essential. They decide on a coordinated lift and gather the necessary equipment, including a lifting mat designed for safe animal handling. |

|---|---|

| Preparing for the Lift | Ellie and Tom position themselves on either side of Max, ensuring they have a secure grip on the lifting mat handles. They make sure that their feet are shoulder-width apart, knees slightly bent, and that they’re using proper posture to keep their backs straight. They confirm their plan and agree on a verbal cue to lift simultaneously. |

| Executing the Lift Safely | On the count of three, Ellie and Tom lift Max smoothly, using their legs rather than their backs to avoid strain. By lifting together and keeping Max as close to their bodies as possible, they minimise the risk of injury. They avoid twisting their torsos, instead taking small steps as they move toward the examination table. Once there, they gently lower Max onto the table, using the same technique to avoid sudden movements. |

| Aftercare and Reflection | After securing Max on the table, Ellie and Tom take a moment to assess their posture and any strain they may have felt, ensuring they continue to practice safe manual handling techniques. They also log the incident in the workplace’s manual handling safety record, noting any adjustments that might improve the process in future lifts. |

Key Takeaways

This scenario demonstrates the importance of:

- Planning the Lift: Assessing weight and condition, and using a team approach for heavier animals.

- Using Equipment: Employing a lifting mat or sling to secure the animal safely.

- Proper Body Mechanics: Maintaining good posture, using leg strength, avoiding twisting, and keeping the load close.

- Clear Communication: Coordinating with colleagues through verbal cues to ensure a smooth, safe lift.

By following these steps, Ellie and Tom minimise the risk of manual handling injuries, ensuring their safety and providing comfortable handling for Max.

Aggressive owners

Dealing with clients is sometimes harder than dealing with their pets. Having to deal with stressed owners in an animal emergency is a common occurrence. Some owners may be upset, frustrated or worried and some may become aggressive.

Good communication skills will help reduce the likelihood of verbal abuse or physical aggression. If you have a client who is aggressive, do not take them into a room that does not have two exits. Remember that in every consult or preparation room there are sharp instruments such as needles and scissors.

If the owner becomes aggressive you may have to tactfully ask them to leave the room. For example, you may have to say, “I can see that you are becoming upset over the stress of your pet, but I feel it would be better if you waited out in reception while staff look after your pet.” Or “The reason your pet is acting this way is that he/she sees that you’re upset, and we need to treat them.”

If you are concerned for your safety or the safety of any animals or other people present, do not hesitate to ask for assistance.

Strategies for dealing with aggressive owners

| Stay Calm and Professional |

|

|---|---|

| Listen Actively |

|

| Set Boundaries and Stay Safe |

|

| Use Empathy to Defuse Tension |

|

| Focus on the Issue, Not the Behaviour |

|

| Use a Low, Calm Tone of Voice |

|

| Know When to Involve a Supervisor |

|

| Offer Solutions or Alternatives |

|

| Stay Patient and Avoid Personalising Aggression |

|

| Follow Up After the Incident |

|

Case Study

It’s a busy afternoon at Happy Paws Animal Care, and Sarah, a veterinary technician, is assisting at the reception desk when a client, Mr. Taylor, arrives with his injured cat, Whiskers. Mr. Taylor is visibly upset and frustrated because he feels his wait time has been too long. He raises his voice, demanding immediate attention and questioning the quality of care at the facility. Sarah recognises the potential for escalation and prepares to handle the situation calmly.

Situation and Response |

|---|

|

Step 1: Stay Calm and Listen Actively Step 2: Show Empathy and Acknowledge His Feelings Step 3: Explain the Situation Clearly and Apologise for the Delay Step 4: Offer a Solution and Follow Through Step 5: Maintain a Calm and Positive Tone |

Outcome |

|---|

| Mr. Taylor calms down and thanks Sarah for her understanding and reassurance. Whiskers is seen shortly after, and Sarah follows up with Mr. Taylor to ensure that he feels satisfied with the care received. By employing empathy, clear communication, and prompt action, Sarah successfully de-escalates the situation, demonstrating professionalism and care. |

Key Takeaways |

|---|

|

This scenario highlights:

Through these strategies, Sarah manages to turn a tense encounter into a productive and respectful interaction, protecting the staff’s working environment and providing a positive experience for the client and their pet. |

Mental trauma

The stress of witnessing an accident or serious injuries, or working with animals in emergencies can cause lasting trauma for the first aider, other animals, medical staff and bystanders.

Debriefing with colleagues about the incident and your involvement can help you process any potentially traumatic experiences and maybe a documented step in your workplace’s emergency policies and procedures. To minimise the risk of mental trauma or other mental health concerns related to your work, you may need to seek out mental health support services in your workplace or local area.

Working with animals can be rewarding, but it can also expose caregivers to significant mental and emotional challenges. Here are some examples of mental trauma that may arise from working in animal care:

Trigger Warning

The following table goes through some mental and emotional examples and descriptions that may distress learners.

| Mental/ Emotional Challenge | Description | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Compassion Fatigue | Compassion fatigue results from the constant emotional demands of caring for animals in distress, leading to feelings of exhaustion and decreased empathy. | An animal care worker may feel numb or detached after repeatedly witnessing animals in pain or when euthanasia is required. |

| Moral Distress | This occurs when a caregiver knows the right course of action for an animal but is constrained by workplace policies or resource limitations. | An attendant may feel distressed when unable to provide ideal care due to budget cuts, such as denying treatment to animals that could be saved. |

| Grief and Loss | Losing animals, especially those under long-term care, can lead to intense grief similar to that felt with human loss. | An attendant who builds a bond with an animal over time may experience significant grief when the animal passes away. |

| Burnout | The physical and mental exhaustion from a high-stress environment and emotional strain can lead to burnout, affecting motivation and mental health. | Long hours, especially with high needs or large numbers of animals, can lead to overwhelming fatigue, apathy, or anxiety. |

| Secondary Traumatic Stress (STS) | This is a form of trauma experienced by those exposed indirectly to traumatic events or distressing stories, affecting their mental health. | Animal rescue workers exposed to stories of abuse or seeing animals come in with injuries from neglect may feel traumatised. |

| Helplessness and Guilt | The inability to help every animal in need can lead to feelings of helplessness, guilt, and self-blame. | A caregiver may feel guilty for not being able to save an animal with limited resources, or may struggle with guilt over animals needing to be rehomed. |

| Anxiety Related to Aggressive Animals | Frequent interactions with aggressive or unpredictable animals can lead to anxiety and hypervigilance, especially if there’s a risk of injury. | A handler who has been bitten or attacked may develop a fear response or heightened anxiety when approaching similar animals. |

| Emotional Trauma from Euthanasia | Euthanasia, though sometimes necessary, can cause emotional pain, leading to feelings of sadness, guilt, or moral conflict. | Regularly euthanising animals may lead a caregiver to experience recurring sadness or questioning of their values and purpose. |

| Stress from Abuse or Neglect Cases | Encountering animals that have been abused or neglected can cause caregivers to experience deep sadness, anger, or vicarious trauma. | A worker at a shelter might feel disturbed and traumatised after handling animals with visible signs of abuse, such as scars or malnutrition. |

| Witnessing Severe Injury or Death | Exposure to traumatic injuries or witnessing animal deaths can lead to acute stress, nightmares, or intrusive thoughts. | A rescue worker may have flashbacks or nightmares after handling a case where an animal suffered severe injury or died unexpectedly. |

Other hazards to consider

The following table provides a summary of some of the other hazards that may occur to yourself and to other people, their effects and safe work practices that you can implement to ensure a safe course of action while providing first aid to an animal.

| Hazard | Possible harmful effects to self and others | Methods to control or minimise risk |

|---|---|---|

| Traffic | Hit by a vehicle while attending to the animal |

|

| Environmental conditions |

|

|

| Other | Other types of injury | Assess for potential hazards on and around the scene of the incident or situation, including:

|

Potential risks to the injured animal

Hazards and risks to the animal requiring first aid include additional injury to themselves if they are spooked or by being jolted against the hard materials that are used when transporting the animal.

An injured animal can be at risk of further harm while moving them, particularly if they have spinal injuries or are experiencing shock.

It is important to note when dealing with macropods (kangaroos, wallabies and pademelons) that the stress alone of being captured can cause myopathy (any disease that affects the muscles that control voluntary movement) leading to death. The animal does not have to have suffered any injury for this to occur. They may develop rhabdomyolysis (disintegration of the muscle fibres). This condition can occur anywhere from 24 hours post the stress up to a few weeks after the incident. The macropod will show stiffness and paralysis in the hindquarters, progressing to complete paralysis as it ascends the body. It will also salivate excessively. Death will typically occur within 2-14 days after the stressful incident (Ulyatt 2021).

With this in mind, care must be taken to ensure injured animals on the scene, regardless of species, are:

- not injured or harmed further (for example, go into shock) by human intervention

- not at risk of escaping, causing further injuries to themselves.

The following table provides a summary of some of the hazards that may occur to the injured animal, their effects and safe work practices which you can implement to ensure a safe course of action while providing first aid.

| Hazard inflicted by | Possible harmful effects to the injured animal | Control methods to reduce hazard/risk |

|---|---|---|

| The injured animal |

|

|

| Traffic | Hit by a car |

|

| Environment |

|

|

| First aider | Causes further injury or pain when assessing, capturing or transporting the animal |

|

Potential risks to other animals

In a first aid situation, it is important to consider other animals in the area as well as other people. If a client brings an injured animal to the veterinary clinic, it is likely that there will be other animals present in the waiting room. If you are out in the field, other animals present may include dogs being walked nearby, other pets of the same owner or other animals in the same stable, herd or flock.

The following table provides a summary of some of the hazards that may occur to other animals, their effects and safe work practices which you can implement to ensure a safe course of action while providing first aid to the injured animal.

| Hazard inflicted by | Possible harmful effects to other animals | Control methods to reduce hazard/risk |

|---|---|---|

| Animal needing first aid |

|

|

| Traffic |

|

|

| First aider |

|

|

Minimise risks

Take care not to become a casualty yourself while administering first aid. Use protective equipment and clothing where necessary. If you need help, send for it immediately.VetNurse.co.uk, n.d.

No matter where you work, there will be health and safety procedures that you must follow, and this includes when handling animals. By following the applicable safety procedures, you are ensuring a safe working environment is maintained. This will include the way you handle an animal, all the way through to using personal protective equipment (PPE).

1. Implement Clear Safety Protocols

|

2. Understand Animal Behaviour

|

3. Proper Handling Techniques

|

4. Secure the Environment

|

5. Use Personal Protective Equipment (PPE)

|

6. Minimise Exposure to Zoonoses

|

7. Control Stress in Animals

|

8. Ensure Regular Health Checks

|

9. Develop Emergency Response Plans

|

10. Control Aggression and Behavioural Risks

|

11. Provide Mental Health Support for Staff

|

12. Manage Manual Handling Risks

|

13. Control Risks from Aggressive Owners

|

Personal protective equipment

Use the required personal protective equipment (PPE) when dealing with animals. It is vital that all PPE is used in line with the manufacturer’s instructions and workplace procedures.

PPE must fit correctly to ensure it gives you the protection required when handling animals.

Review the following PPE that may be used when handling animals:

| PPE (correctly fitted) | Benefits |

|---|---|

| Examination gloves | Change after each patient to prevent transmission of disease between patients; protection from zoonotic diseases |

| Animal handling gloves/gauntlets | Protection from bites and scratches |

| Boots | Protection from the ground/road or an animal stepping on the foot |

| Sunscreen; wide brimmed hat; shirt with collar and sleeves; long pants; rain jacket with hood; gumboots; warm clothing | Protection from prolonged exposure to UV radiation, heat, cold, rain, rough or wet terrain and insects |

| Fluro vest | Provides high visibility to surrounding traffic, reducing the risk of a traffic incident |

| Non-slip, closed in shoes | Protection from zoonotic diseases and slipping |

| Scrub top over uniform, disposable aprons or gowns | Change after each patient to prevent transmission of disease between patients; protection from zoonotic diseases; keeps uniform clean |

Other safety equipment

Other safety equipment includes communication devices, such as mobile phones and radios.

Tip

Knowledge Check 2

Scenarios where PPE is used and how it provides protection

In the table below are some scenarios of animals being injured and examples of the types of PPE you would use in the scenario and how it would protect you.

Scenario |

PPE Used |

How does it protect you? |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Dog with a deep wound | PPE Used: Gloves (disposable or heavy-duty). | Protection Provided: Prevents direct contact with blood and reduces the risk of infection or disease transmission. |

| 2. A cat in pain with a fractured leg | PPE Used: Arm guards and gloves. | Protection Provided: Shields arms and hands from scratches and bites caused by the cat’s defensive reactions. |

| 3. Snake with a suspected injury to its scales | PPE Used: Snake hook, gaiters, and gloves. | Protection Provided: Prevents bites and reduces the risk of venom exposure during handling. |

| 4. Bird with a broken wing | PPE Used: Towel and gloves. |

Protection Provided: Minimises pecking and scratching injuries while restraining the bird safely. |

| 5. Horse with a laceration on its flank | PPE Used: Steel-capped boots, gloves, and safety goggles. | Protection Provided: Protects feet from accidental hoof strikes, hands from infection, and eyes from dirt or debris kicked up. |

| 6. Injured rabbit with a skin tear | PPE Used: Gloves and a gown. | Protection Provided: Reduces the risk of contaminating the wound and protects the handler from scratches. |

| 7. Cow with a swollen hoof | PPE Used: Overalls, gloves, and boots. | Protection Provided: Prevents contamination from mud, manure, or pus and shields the handler from accidental kicks. |

| 8. Kangaroo with a leg injury | PPE Used: Arm guards, gloves, and a protective vest. |

Protection Provided: Reduces the risk of scratches or chest blows caused by the kangaroo's strong claws and legs. |

| 9. Dog experiencing seizures after an injury | PPE Used: Gloves and a muzzle (if safe to apply). | Protection Provided: Prevents bites and limits direct contact with saliva or fluids during seizure handling. |

| 10. Sheep with a deep puncture wound | PPE Used: Overalls, gloves, and boots. | Protection Provided: Shields the handler from infectious material and protects feet from trampling. |

| 11. Aggressive goat with a leg injury | PPE Used: Gloves, helmet, and protective vest. | Protection Provided: Protects against headbutts and reduces injury from defensive bites or kicks. |

| 12. Lizard with a tail injury | PPE Used: Gloves and an apron. | Protection Provided: Minimises contact with potential pathogens on the lizard’s skin and protects clothing from fluids. |

| 13. Injured bat with a broken wing | PPE Used: Gloves and goggles. | Protection Provided: Prevents contact with potentially infectious bites or saliva and shields eyes from wing flapping. |

| 14. Piglet with a leg injury | PPE Used: Gloves and boots. | Protection Provided: Protects against exposure to faecal matter or other contaminants in the pen. |

| 15. Injured alpaca with a neck wound | PPE Used: Gloves, protective vest, and safety goggles. | Protection Provided: Protects the handler from spit and sudden defensive movements. |

The assistance required by the animal involved in the incident will depend on the level of emergency as well as its species and the particulars of the situation. In other words, while first aid may be necessary, the urgency of transporting the animal to a vet will depend on the seriousness of the situation. You may also need to follow other workplace policies and procedures, such as reporting animal abuse to a welfare body.

Workplace policies and procedures for first aid

Your workplace should have animal first aid emergency policies and procedures documented for all staff members to follow. These policies are in place to protect the welfare of staff and the animals in their care.

The Australian Veterinary Association has examples of a multitude of policies covering a wide range of topics relating to animals. For information, review their policies and position statements. Ask your workplace if they have specific policies and procedures that need to be adhered to.

Some of the subjects covered by the Australian Veterinary Association include:

- Animal abuse

- Euthanasia of injured wildlife

- Zoos, aquaria, sanctuaries and animal parks

- Guidelines for the tethering of animals

- Companion animals confined to vehicles

- Heat stress in the horse

- Transport of horses.

Always follow the policies and procedures in your own workplace.

Below is an example from Happy Paws of their Animal First Aid Emergency Policy and Procedure.

Case Study

Happy Paws Animal Care: Animal First Aid Emergency Policy and Procedure

Policy Title: Animal First Aid Emergency Policy

Policy Owner: Happy Paws Animal Care Management

Last Reviewed: [Date]

| Purpose |

|---|

| This policy outlines Happy Paws Animal Care’s approach to animal first aid in emergency situations, ensuring all staff respond swiftly and effectively to minimise injury or distress to animals and enhance the safety of both staff and animals. |

| Scope |

|---|

| This policy applies to all employees, volunteers, and trainees at Happy Paws Animal Care who may be involved in handling first aid emergencies involving animals under our care. |

| Policy Statement |

|---|

|

Happy Paws Animal Care is committed to:

|

First Aid Procedure for Animal Emergencies

| 1. Assess the Situation |

1.1 Secure the Scene

1.2 Evaluate the Animal’s Condition

|

|---|---|

| 2. Call for Assistance |

2.1 Alert Appropriate Personnel

2.2 Gather First Aid Supplies

|

| 3. Provide First Aid |

3.1 Stabilise the Animal

3.2 Administer First Aid According to Injury Type

3.3 Continue Monitoring

|

| 4. Transport to Veterinary Care |

4.1 Prepare for Safe Transport

4.2 Communicate with Veterinary Staff

|

| 5. Document the Incident |

5.1 Complete an Incident Report

5.2 Review for Improvement

|

| Roles and Responsibilities |

|---|

|

| Training |

|---|

|

| Related Documents |

|---|

|

| Review and Updates |

|---|

| This policy will be reviewed annually and updated as necessary to reflect best practices and any new guidelines in animal care and emergency response. |

Organisational emergency procedures

Your workplace will have procedures for a variety of subjects related to your particular field of work. Work health and safety (WHS) procedures may include:

- handling animals

- hazard identification and risk minimisation

- manual handling techniques

- controlling the spread of disease, infection control and biohazard management

- incident reporting

- seeking advice from supervisors

- use of personal protective equipment (PPE)

- emergency procedures

- potential escape of an animal

- injury to an animal or other animals, staff and potentially the public.

For example, you should follow your workplace procedures for manual handling of large animals, such as doing a two-person lift of animals heavier than 15-20 kgs.

Emergency plan

An emergency plan is a written set of instructions that outlines what workers and others at the workplace should do in an emergency.Safe Work Australia, 2012

Your organisation should have a tailored animal policies and procedures document to follow in the event of needing to apply first aid so that your response is planned, coordinated, prompt and effective.

Ask your animal care workplace to provide and discuss their animal first aid emergency policies and procedures with you, then practice them until you feel confident. Being confident about what to do in an emergency will help reduce stress and prevent mistakes or further injury to animals.

Details may include:

- your responsibilities during an emergency

- communication protocols

- when to notify specific emergency services

- contact details for medical assistance

- contact details of key staff to contact for assistance

- how to alert staff in the workplace to an incident or potential emergency

- other back-up services available during an emergency, including contact details

- location of emergency equipment, such as a first aid kit

- emergency equipment and procedure training tailored to individual roles in the workplace

- a review process after the emergency.

The following checklist is adapted from a draft provided by Safe Work Australia. Your workplace may have some or all the items on this checklist for their own first aid emergency plan.

| Animal first aid emergency policies and procedures |

|---|

|

Responsibilities

|

|

Emergency contact details

|

|

First aid

|

|

Post-incident follow-up

|

|

Review

|

Review Safe Work Australia’s Emergency plans and procedures for more information or speak to your supervisor about the policies and procedures in your workplace.

Reading

Click on the following links below for more information from Safework Australia.

Video

As the following video explains, during an emergency it can be incredibly hard to swiftly find out who to contact or where to go for help. Having a plan will save precious time and could mean saving an animal’s life. Always have important contact and location information stored on your phone, a first aid kit handy and know where to find emergency 24-hour help wherever you go and before you go (Animal Ethics Infolink n.d.).

Assess your options for assisting the animal

One of the steps in your workplace animal emergency policies and procedures document should include assessing options for assisting an animal during an emergency. The process for assessing the options is also known as triage.

Triage is the process of determining of urgency in which an animal requires medical attention. The urgency depends on the likelihood that the animal will die, deteriorate and/or suffer pain.

Your first triage decision is to determine whether it is safe to give the animal first aid. There are two situations where you should not provide first aid to an animal requiring it:

- When the time taken to apply first aid will cause the animal to deteriorate. In these situations, you must transport the animal to the vet as soon as possible.

- When providing first aid is too risky for either your safety or the animal’s. In these situations, ask for assistance to capture and transport the animal to the vet.

If it is appropriate to provide first aid, you will need to assess the physical condition and vital signs of the animal to determine what help it requires. The first aid treatment(s) you decide to apply should be according to the animal’s medical needs, which you will learn about later in this module.

However, in brief, examine the animal to determine if they are ill, have been involved in an accident, are under immediate threat of loss of life, or can wait for veterinary assistance. Then, assess the best steps to take, using the seven principles of first aid to guide you:

- Preserve life

- Prevent deterioration

- Promote recovery

- Take immediate action

- Calm the situation down

- Call for medical assistance

- Apply the relevant treatment.

You are to follow your animal workplace policies and procedures throughout each step.

Once you have made your assessment, your options for assisting the animal may include any one of the following (the order may change depending on the urgency):

- provide immediate first aid to the animal or seek assistance

- prepare the animal for transport

- contact your destination clinic and notify them that you are on the way

- transport the animal to the veterinary hospital

- notify other staff of the incident

- if you haven’t already as part of a previous action, notify your supervisor.

Triage occurs as soon as you arrive on the scene or take the phone call. You will be assessing the animal’s need for first aid versus immediate transport. In other words, you need to decide how long, if at all, veterinary treatment can be delayed. The video, 'Triage: Sorting Urgency' (2:34 min), explains that the goal of triage is to quickly sort casualties into three different categories.

Appropriate triage will give the animal the best chance of survival.

Watch

Watch the following video for more information about how to triage an emergency situation.

For further information on triage, review the article How Emergency Animal Hospitals Work (the triage system).

Communication during triage

Communication skills are vital during triage to obtain correct information swiftly. There are a variety of appropriate techniques that can be useful to obtain and convey key information effectively in your animal care workplace, especially when seeking advice and assistance from your supervisor or communicating with clients and other staff.

Triage may take place over the phone or in person. Phone triage occurs when a person calls in to describe a potential animal emergency. The person taking the phone call may provide lifesaving first aid advice over the phone, such as how to control bleeding.

In-person triage occurs when the animal presents at the clinic or you are in the field with the animal. The initial triage includes taking a history from the owner, if possible, and assessing the vital signs of the animal. For either type of triage, the aim is to determine the risk to the animal and how immediately it needs veterinary attention.

Whether talking to the client over the phone or in person, remember that some owners will panic and exaggerate the problem and others will be very calm and underplay what is occurring. It is best to work with the thought in mind:

"If you are concerned, I am concerned".

It is vital that you remain calm. The person may be emotional, anxious, in shock or in freeze mode. If you are calm, you will not feed into the state they are in. Calmly lead them with questions to gather from them what the situation is and what they are seeing.

Don’t forget, if you are not confident triaging an animal, seek assistance.

Phone triage

“Owners can provide significant medical assistance at the scene of the injury. At the time of the initial telephone call, the owner should be questioned about the level of consciousness, breathing pattern, type of injury or toxicity, and even some aspects of the animal's perfusion (eg, gum color, level of responsiveness, heart rate). The first concern is for the safety of the owner.” (Linklater 2020)

Phone triage has different challenges compared to triaging in person because you are unable to read body language. Further information on how to communicate to get the best possible results will be explored next.

Remember not to diagnose. You can stress to the owner that it is essential for them to arrive ASAP as you are very concerned, but do not give a diagnosis. It is illegal for anyone that is not a vet to diagnose or suggest a diagnosis. However, you can provide first aid advice.

If you receive a phone call about a potential emergency or first aid situation, use the following procedure to collect all the vital information:

- Ask the person’s name and the phone number from which they are calling. This is important in the event the call is cut off.

- Ask about the nature of the emergency, including a very basic assessment of the physical condition and vital signs to determine the seriousness of the emergency:

- Is the animal breathing?

- Is the animal conscious?

- If the answer is “no” to either of the previous questions, the animal needs to be brought to a vet immediately (life-threatening). If the animal is breathing and conscious, you may be able to spend a little more time on the phone and provide first aid advice.

- If you think it is safe to spend more time on the phone, ask for the patient's name, breed 2020and more details about the incident. This will allow you to better prepare for their arrival as well as provide the owner with appropriate transport advice.

- Before hanging up, ensure the person knows where the clinic is and ascertain how long it will take for them to arrive.

Watch

Watch the following video, ‘Client Communications: The Art of Phone Triage’ (4:50 min), for more information regarding the processes involved in phone triage.

Case Study

Happy Paws Animal Care- Triage Process

At Happy Paws Animal Care, the triage process is critical for managing emergency cases effectively and ensuring that each animal receives appropriate care based on the severity of its condition. Triage levels are divided into four main categories:

- Level 1 - Critical: Life-threatening conditions requiring immediate intervention to stabilise the animal, such as severe trauma, respiratory distress, or collapse.

- Level 2 - Urgent: Serious but not immediately life-threatening cases that need prompt attention within 30 minutes to prevent the condition from worsening. This includes injuries like broken bones, deep cuts, and moderate pain.

- Level 3 - Stable: Non-life-threatening issues that can wait up to an hour or more without significant risk to the animal’s health, like minor cuts, mild limping, or non-severe infections.

- Level 4 - Routine: Cases that are not emergencies and do not require urgent intervention, typically seen in scheduled appointments for general check-ups or minor health concerns.

Each animal arriving in an emergency at Happy Paws is assessed by a veterinary technician or veterinarian, who assigns a triage level based on visible symptoms, vital signs, and the likely progression of the condition. Here’s how this process was applied to five animals recently brought to Happy Paws.

Triage Assessment

Animal 1: Bella the Labrador (Triage Level 1 - Critical)Situation: Bella, a 5-year-old Labrador, arrived at Happy Paws after being hit by a car. She was unresponsive, had laboured breathing, and displayed signs of severe internal bleeding, including pale gums and a weak pulse. Triage Process: The veterinary team quickly assessed Bella’s vital signs, noting her deteriorating condition. Due to the life-threatening nature of her injuries and her declining vital signs, Bella was immediately assigned a Level 1 - Critical status. Reasoning: Bella’s injuries required immediate intervention to stabilise her and prevent further deterioration. She was rushed into emergency surgery to control internal bleeding and repair damage, with the team prioritising her due to the life-threatening risks. |

Animal 2: Milo the Cat (Triage Level 2 - Urgent)Situation: Milo, a 3-year-old domestic shorthair, was brought in with a visibly fractured front leg after jumping off a high fence. He was conscious but in obvious pain and was struggling to walk. Triage Process: Upon examination, Milo’s broken limb and level of pain were assessed by the veterinary technician. Although not immediately life-threatening, his injury risked worsening without prompt treatment. Triage Level: Level 2 - Urgent Reasoning: Milo’s condition required attention within 30 minutes to manage his pain and prevent further complications from the fracture. He was prioritised accordingly and given pain relief while preparing for X-rays and further treatment. |

Animal 3: Daisy the Rabbit (Triage Level 3 - Stable)Situation: Daisy, a 2-year-old rabbit, was brought in with mild nasal discharge and sneezing, suggesting a possible respiratory infection. She appeared alert and was still eating and drinking normally. Triage Process: The veterinary team assessed Daisy’s respiratory rate and condition, determining that she did not show severe signs of respiratory distress. They also confirmed that her other vitals were stable. Triage Level: Level 3 - Stable Reasoning: As Daisy’s condition was not life-threatening and her symptoms were relatively mild, she was assigned a stable triage level. Her case was seen within an hour, as her symptoms did not pose an immediate risk to her health but still required evaluation and possible treatment. |

Animal 4: Max the Golden Retriever (Triage Level 4 - Routine)Situation: Max, a 7-year-old Golden Retriever, came in with a mild skin irritation on his belly that had been gradually worsening over the past few days. He was still active and showed no signs of pain or distress. Triage Process: The veterinary technician examined Max’s skin, noting minor redness and a few small sores. Max’s behaviour and overall condition were stable, with no signs of serious discomfort or complications. Triage Level: Level 4 - Routine Reasoning: Since Max’s condition was not an emergency, he was assigned the lowest triage level, meaning he could wait without any risk to his health. This allowed the veterinary team to prioritise more urgent cases first, addressing Max’s skin condition later in a routine appointment. |

Animal 5: Rocky the Cockatoo (Triage Level 2 - Urgent)Situation: Rocky, a 4-year-old Cockatoo, was brought in by his owner after he accidentally ingested a small amount of cleaning solution. Rocky was lethargic, vomiting, and had watery eyes, showing signs of poisoning. Triage Process: The veterinary team assessed Rocky’s symptoms and realised he was experiencing the early stages of toxin ingestion. Although not yet life-threatening, his symptoms suggested that prompt intervention was needed to prevent further deterioration. Triage Level: Level 2 - Urgent Reasoning: Due to the potential risks associated with the ingestion of toxins, Rocky was given an urgent triage level and was treated within 30 minutes. Activated charcoal and other necessary treatments were administered to minimise the effects of the toxin. |

The triage process at Happy Paws Animal Care allows the team to prioritise cases based on the severity of the animal's condition. This approach helps ensure that critical cases receive immediate care, while stable and routine cases are managed appropriately. By following this structured triage process, Happy Paws is able to provide timely and efficient treatment, optimising outcomes for every animal that comes through their doors.

Active listening skills

Communication skills are especially important to facilitate speedy but accurate triage, increasing the likelihood of the animal’s survival. The overarching communication skills are to:

- speak clearly and calmly when asking for help and seeking or giving information to other staff or clients in the workplace.

- use active listening and questioning techniques to gain information and to confirm that you have understood what you have heard.

When speaking to the owner or other people involved in the animal incident, remember to fully concentrate so that you understand the complete message by using active listening.

Examine and apply the following steps to active listening:

- Pay attention – look at the speaker

- Show that you are listening – nod, smile, say ‘yes’ occasionally

- Provide feedback – reflect the words back to the person and ask questions to make sure you have the correct information

- Defer judgement – give the person the time they need to finish conveying the information before offering advice

- Respond appropriately – remain open, honest and respectful (Mind Tools Content Team n.d.).

Review the video 'Improve Your Listening Skills with Active Listening' (2:39 min) to further sharpen your listening skills.

Open and closed questioning

We have discussed active listening. Now it’s time to learn how to ask and use open-ended and closed-ended questions when seeking information from owners or witnesses, or assistance and advice from your supervisor or others.

Open-ended questions will give you more than just a ‘yes’ or ‘no’ response. The aim is to gain the information you need to make good first aid decisions. Ask appropriate questions from the outset of the incident to gain a short, sharp history of what has happened to the animal or to gain specific advice from your supervisor.

Open-ended questions are designed to introduce an area of inquiry without shaping the contentRoyal Canin, 2020

‘Funnel’ your questions by beginning with open-ended questions and then end with closed-ended questions. The closed-ended questions will help gain specific details or information that may not have been communicated through open questioning. Therefore, funnel your questions by asking broad open-ended questions. Finish off with closed (clarifying) questions.

Why are open-ended questions important?

- The conversation is controlled from the person asking to the person being questioned.

- They cause a person to think and reflect.

- Answers may include background information and details that would not have been evident otherwise.

- Can be used in conjunction with active listening – ask an open-ended question related to the information the participant has given you when they have finished talking.

Open-ended questions begin with words like ‘what, how, why, describe, tell me about or what do you think about’. Examples of open-ended questions are:

For gaining information during triage:

- What happened to Ramona the cat before you came into the vet today?

- What concerns do you have?

- Tell me about the behaviours you have seen Watermelon the guinea pig display.

- What other issues has your animal been experiencing?

Seeking advice or assistance:

- What is the best way to stop this bleeding?

- How can I best support this animal when I pick it up?

- What do I do next?

Examples of closed-ended questions could include:

- Has your dog been to us before for grooming?

- How old is your cat?

- Is the guinea pig urinating?

- When was the last time he ate something?

You will notice that the open-ended types of questions are broad, with an aim to gather information without directing the conversation too much. Open-ended questions allow the other person to provide as much detail as they feel is appropriate. There are no right or wrong open-ended questions, but always remember the aim and shape your questions to address your specific situation to get the animal in your care on the path to speedy recovery (Diaz et al. 2022).

Closed-ended questions are more specific, requiring ‘yes’ or ‘no’ answers or very specific information. Closed-ended questions are still very useful. You will gain clearer, more relevant results by collecting information through the use of open-ended questions at the start of the conversation, then clarifying and refining that information with closed-ended questions. (Diaz et al. 2022). The process of refining the information is called ‘funnelling’, as represented in the following figure.

If the conversation takes place on the phone, it is often more difficult to assess the non-verbal cues. Therefore, using these communication techniques will help you to check and confirm that you understand the information you are receiving.

Knowledge Check 3

Wild bird strike

Heath problem: Loss of consciousness from impact