We know that double-entry accounting requires credits and debits to be equal to each other. We also know that to make something balanced, there are usually adjustments that are made to achieve that balance. In this section, we'll cover recording general journal entries for balance day adjustments.

Before moving on, answer the following questions to check your understanding of recording depreciation.

Have a look at this video which provides a glimpse into the daily life of an accountant, with a focus on the purpose and methods of balance day adjustments.

Adjust Expense Accounts and Revenue Accounts for Prepayments and Accruals

As a reminder, the primary financial statements used are the profit and loss statement, balance sheet and statement of cash flows. The balance sheet or statement of financial position reports the assets, liabilities, and owner’s (stockholders’) equity at a specific time, such as June 30. The statement of cash flows reports the sources and uses of cash by operating activities, investing activities, financing activities, and certain supplemental information for the period specified in the statement's heading.

The profit and loss (P&L) statement is of great importance because it tells whether the business is making a profit or loss. This statement may be kept for any period of time. For example, at start-up, they may be produced monthly. Annual P&L statements are produced at the end of the year to prepare income tax.

The profit and loss statement only shows revenues, expenses, gains and losses. It will not display money you receive or money paid out in an accrual-based system.

It isn’t unusual to adjust accounts, which is done commonly to record one-off situations, changes that occurred after the initial recording, and to adjust what period will reflect an expense or profit.

You may classify adjustment entries as prepayments (revenue/expense) or accruals (revenue/expense).

Why do we need Day Balance Adjustments?

It is necessary to make certain adjustments in the accounting records to ensure all income and expenses that relate to the current financial reporting period are identified and properly reported in the current period. They are done to record revenue and expenses in the correct accounting period so that actual profit for the period can be accurately reported.

Watch this video to get a comprehensive view of balance day adjustments.

You may have picked up on the idea that balance day adjustments are only necessary for an accrual-based accounting system as revenue or expenses may be recognised and paid/received at different times. Cash accounts are recorded based on money in/out, so no adjustment is necessary for balancing.

Most small businesses will not have many balance day adjustments to make, as accounts such as insurance are usually paid on a monthly basis, and most computerised payroll systems calculate leave liabilities with each pay calculation.

The most common balance day adjustments used in small businesses are:

- Writing off bad debts

- Correction of errors

- Calculating depreciation

- Prepaid expenses

In determining what balance day adjustments need to be made at the end of an accounting period, the issue of materiality needs to be considered.

AASB 1031 Materiality accounting doctrine states that only material of significant information should be revealed in the preparation of financial reports.

For further detail, go to the AASB website and look at the Table of Standards. This contains links to further information on each of the standards.

The best example of balance a day adjustment occurs with depreciation. The accounting entry for depreciation involves a journal entry that creates a depreciation expense and an accumulated depreciation account. Depreciation expense is listed on the Profit & Loss Statement, while Accumulated Depreciation is a negative asset, listed in the asset section of the Balance Sheet. It, therefore, reduces the amount of the asset. If an expense increases, it is a debit transaction; therefore in the journal, it will be a debit, and in the ledger, it will always have a debit balance. Accumulated Depreciation must decrease an asset, and to decrease an asset, you must credit the transaction.

Profit and Loss Statement → depreciation expense is debited.

Balance Sheet → accumulated depreciation is credited.

This video describes what is necessary to manage adjustments for non-current assets (such as copyright or IP) and how to deal with the disposal of fixed assets.

Disposal of fixed assets

Fixed assets may be sold anytime during their useful life. This leads to derecognising the asset from the balance sheet and recognising any resulting gain or loss in the income statement.

The accounting for disposal of fixed assets can be summarised as follows:

- Record cash received or the receivable created from the sale: Debit - Cash/Receivable

- Remove the asset from the balance sheet: Credit - Fixed Asset (Net Book Value)

- Recognise the resulting gain or loss: Debit/credit- Gain or Loss (Income Statement)

Example

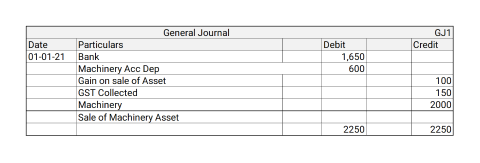

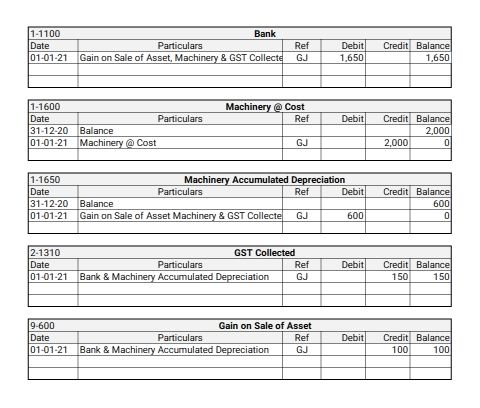

ABC Pty Ltd purchased a machine for $2000 on 1st January 2019, with a useful life of 5 years and an estimated residual value of $500. The machine was being depreciated on a straight line basis, however, ABC Pty Ltd decided to sell the asset on 1 January 2021 for $1500 +($150.00 GST) to raise cash to purchase a new machine.

- Record cash received or the receivable arising from the sale to record the disposal of the fixed asset + any GST:

- Debit - Cash $1650.00

- Credit - GST Collected $150.00

- Remove the asset from the balance sheet As a fixed asset is recognised in the balance sheet at the Net Book Value (i.e. Cost less Accumulated Depreciation), the machine will be removed from the accounts of ABC LTD in the next two steps.

- First, the Machine Cost must be removed by crediting the ledger: Credit - Machine Cost $2000.00

- Second, the Accumulated Depreciation of the machine must be removed by debiting the ledger:

- Year 1 – 2019 Depreciation $150.00 (6 months)

- Year 2 - 2020 Depreciation $300.00 (12 months)

- Year 3 – 2021 Depreciation $150.00 (6 months)

- The combined effect of the above two transactions would be to remove the machine's net book value of $1400 (2000 - 600) from the balance sheet. Accumulated

- Recognise the resulting gain or loss on the sale of the machine ABC Pty Ltd received $1500 for an asset with a balance sheet of $1400. It, therefore, earned a gain of $100. The gain will be recorded as follows:

Credit - Gain on Disposal $100.00

The Disposal Account acts as a control account for the entries involving the disposal of fixed assets. Balances from all relevant fixed asset accounts are pooled into the disposal account. The balance figure is the gain or loss on disposal, which is transferred to the income statement.

The General Journal Entry

In this instance, we have totalled the journal entry to demonstrate the total debit entries equals the total credit entries.

General Journal Entries

Transactions which do not fit into specialist journals such as the cash payments journal, the cash receipt journal or sales and purchases journals are recorded in the general journal.

The general journal is formatted in a way which makes it clear and guides the posting to the general ledger. The item is identified as a credit or debit and the transaction described briefly. Business use general journals if the transaction does not need to go through a sub ledger such as accounts receivable or accounts payable.

Here is a reminder of important terms.

- The journal entry is when an entry is made to the appropriate journal.

- The journal is a record that keeps the accounting transactions in the order they occur by date.

- The ledger is the record that keeps accounting transactions by accounts.

- The account is a unit to record and summarise the accounting transactions.

All accounting transactions are recorded through journal entries that show account names, amounts, and whether those accounts are recorded in debit or credit side of accounts.

When you are charged with making journal entries when the business has purchased supplies and paid in cash there are six questions to ask yourself in the following order. An example would be if a business bought supplies for $100 and paid cash.

- What did the business receive? [Supplies]

- If the business received supplies, how would this affect the supplies balance? [It increases supplies balance]

- Which side of supplies account represents the increase in cash? [Debit side (Left side)]

- What did business pay? [Cash]

- Which side of cash account represents the decrease in cash? [Credit side (Right side)]

- Does the sum of debit side amounts equal the sum of credit side amounts? In other words, does this journal entry balance? [Yes - $100 = $100]

There are also six questions that you must ask yourself when you are making journal entries for sales. Again if the business sold its products at $250 and received the full amount in cash and you are making the entry, the following questions must be asked in this order:

- What did Company A receive? [Cash]

- If Company A received cash, how would this affect the cash balance? [Receiving cash increases the cash balance of the company]

- Which side of the cash account represents the increase in cash? [Debit side (Left side)]

- What is the account name to record the sales of products? [Sales]

- Which side of the sales account represents the increase in sales? [Credit side (Right side)]

- Does the sum of debit side amounts equal the sum of credit side amounts? In other words, does this journal entry balance? [Yes - $250 = $250]

This is a useful table to work out if an account should be debited or credited:

| Debit | Credit | |

|---|---|---|

| Increase | Asset/Expense | Income/Liability/Owners Equity |

| Decrease | Income/Liability/Owners Equity | Asset/Expense |

Examples of transactions recorded in the general journal are:

- Opening entries

- To record the assets, liabilities and equity to start the accounting system of a business – to ‘open’ its accounting records (a once only entry)

- The purchase of non-current assets on credit

- Such as the purchase of vehicles, equipment, furniture on credit

- If the above were purchased for cash, the transaction would be recorded in the cash payments journal

- The owner’s contribution of capital in assets other than cash to the business (or drawings of an asset other than cash)

- Such as the owner contributing her / his own computer or office furniture to the business (or taking them from the business)

- If the owner contributes capital in the form of cash, the transaction is recorded in the cash receipts journal (of if he / she takes cash drawings, the transaction is recorded in the cash payments journal).

As an example, we’ll look at the journals for Star Industries, a small business that modifies fitness equipment on a bespoke basis and delivers the equipment to their clients.

Example 1: Opening Entry

| Date | Details | Post Ref. | Debit | Credit |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jan 1 | Bank | 20,400 | ||

| Manufacturing Equipment | 10,200 | |||

| Office Equipment | 9,400 | |||

| Loan from Credit Union | 15,000 | |||

| Capital | 25,000 | |||

| Assets, liabilities and capital at commencement of business |

Notes:

- Details: Describes the entry

- Debit: These are debited to accounts in the ledger

- Credit: These are credited to accounts in the ledger.

Example 2: Purchase of Noncurrent Asset on Credit

| Date | Details | Post Ref. | Debit | Credit |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Feb 8 | Fitness equipment | 1,500 | ||

| GST Paid | 150 | |||

| Weight World | 1,650 | |||

| Purchase of fitness equipment on credit from Weight World |

Notes:

- Details: Describes the entry

- Debit: $1,500 will be debited to fitness equipment account

$150 will be debited to GST Paid - Credit: $1650 will be credited to Weight World account as a sundry creditor

Let’s now enter another transaction into our general journal for Star Industries, depreciating their truck using the straight line method over 10 years. To find the amount per year we divide the total cost (less the scrap value) by 10. The cost of the truck was $10,800, and the scrap value after 10 years is zero. $10800 - 0 = $10800 /10. We therefore need to depreciate the truck by $1,080 each year. Now let’s enter this into the general journal.

| Date | Description | Debit | Credit |

|---|---|---|---|

| December 31 | Depreciation Expense – Truck | 1,080 | |

| Accumulated Depreciation – Truck | 1,080 | ||

| To record the year’s depreciation on Truck |

Now that we have created the General Journal Entry, we must post this entry into the general ledger, by creating two new accounts, Depreciation Expense and Accumulated Depreciation – Truck.

| Date | Description | Ref | Debit | Credit | Balance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 31/12/xx | Accumulated Dep - Truck | GJ1 | 1,080.00 | $1,080.00Dr | |

| Date | Description | Ref | Debit | Credit | Balance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 31/12/xx | Depreciation | GJ1 | 1,080.00 | $1,080.00Cr | |

Another example is prepaid expenses where you have paid an expense in advance. This may happen when you pay a 12-month insurance policy in advance. You will debit the prepaid expense account (which is an asset) for the full amount paid – then, at year’s end, this needs to be adjusted, so the prepaid expense account is credited by the amount used (to reduce it), and the corresponding amount is debited to the expense account related to it.

Alternatively, some businesses may record the full cost incurred immediately as an expense rather than an asset. In this case, the adjusting entry will need to increase (debit) the asset account for the future benefit, which is unexpired and to decrease the expense. (credit), deferring the expense.

Aligning Recorded Revenue

Sometimes, a business receives fees for services before the actual service is rendered. Such transactions are ordinarily recorded by debiting cash and crediting a liability account for the unearned revenue. This situation may also be referred to as deferred revenue and shows the obligation of the business to perform future services. An example of this may come from a magazine publisher offering subscriptions. Let’s say a magazine publisher offers a monthly magazine and receives $720.00 for a three-year subscription.

The cash account would be debited by $720.00 to reflect the cash coming in and the Unearned Subscription Revenue account would be credited $720.00 to reflect the future product the business needs to provide to subscription customers. Each month that the magazine is published and supplied to the customer, the publisher would have fulfilled 1/36th of their obligation. At the end of each month the accounts would transfer $20 from the liability account Unearned Subscription Revenue to the revenue account called Subscription Revenue.

Bad Debt

We all know that not everyone a business sells products or services to will pay for what they have purchased. Because of this, we need to allow for bad debts in our accounting systems.

There are two methods to record debts that are ultimately determined to be uncollectable.

- Allowance Method

- Direct write-off Method

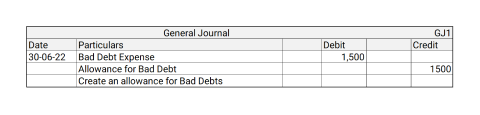

Allowance method

The allowance method of accounting for bad debts is used to give the users of financial statements a more accurate picture as to the value of accounts receivable expected to be collectable at the end of the reporting period. Under the allowance method, a business estimates the number of accounts they believe will become bad debts (doubtful) and then make an allowance for this in their accounts at the end of each year. The allowance can be adjusted throughout the year as well as at the end of the reporting period and is considered an adjusting journal entry.

When the allowance for bad debts is made, the Bad Debt (expense) in the profit and loss account is debited. The provision appears in the balance sheet as an Allowance for Bad Debts (current liability).

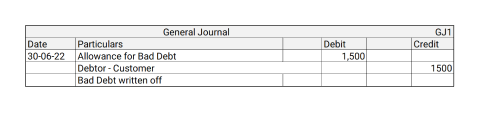

When efforts have been made to collect from a customer, and it has become evident that they will not be paying, it is time to write off the account.

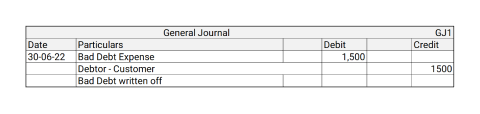

This is accomplished by the following entry:

Direct write off

The direct write-off method is accomplished by removing the debt from the accounts receivable balance and increasing the bad debt expense.

Example:

On 31/03/2021, ABD Company sold goods worth $1,500.00to Customer G with a credit period of 3 months. By the last week of June 2022, Customer G was declared bankrupt and could not pay. ABD should record the bad debt as follows.

Bad debts - DR $1,500.00

Accounts receivable - CR $1,500.00

This is a simple and the most convenient method of recording bad debts; however, it has a significant drawback. It violates the matching principle (expenses should be recorded for the period where the revenue is incurred) of accounting because it recognises bad debt expenses which may be related to the previous accounting period. This is evident from the above example where the credit sale took place in 2021, and the bad debt was written off in 2022.

Compare methods

Here is a look at the difference between the direct write-off method vs the allowance method of managing uncollectable debt.

| Direct write off method: | Allowance method |

|---|---|

| The accounting entry is recorded when the bad debts arise. | An allowance is set aside for possible bad debts, which is a portion of credit sales made during the year. |

| Matching principle | |

| This method is not in accordance with the matching principle. | This method is in accordance with the matching principle |

| Occurrence | |

| The credit sale and the materialising of bad debt usually occur in two accounting periods. | Possible bad debts are matched against the credit sales made for the same accounting period. |

Inventory

There are two systems for accounting for inventory. The key difference between them is the point at which the cost of sales is calculated.

Perpetual Inventory System:

The Perpetual Inventory System tracks the movement of stock the instant it happens. Purchases are directly debited to the inventory account whereas for each sale two journal entries are made: one to record the sale value of inventory and the other to record the cost of goods sold. The purchases account is not used in the perpetual inventory system.

Inventory at the Beginning + Receipts – Sales = Inventory at the end

Periodic Inventory System:

The Periodic Inventory System, relies on a periodic (monthly, quarterly or annual) inventory count. Between counts, there is no record of stock numbers. Under the periodic inventory system, you do not keep a record of what you sold as it happens. Purchases are recorded in the Purchases account and each sale transaction is recorded via a single journal entry. The cost of goods sold account does not exist during the accounting period. It is determined at the end of the accounting period via a closing entry.

Inventory at the Beginning + Purchases – Inventory at the end = Cost of Goods Sold

| Basis for comparison | Perpetual | Periodic |

|---|---|---|

| Meaning | Traces every single movement of inventory, as and when they arise | Inventory records are updated at periodic intervals |

| Basis | Book records | Physical verification |

| Updating frequency | Continuously | At the end of the accounting period |

| Information about | Inventory | Inventory and Cost of goods sold |

| Balancing figure | Inventory | Cost of goods sold |

| Possibility of inventory control | Yes | No |

| Effect on business operation | No effect | Business operations must be halted during valuation |

When compiling your end-of-year statements, you must account for any inventories you hold. For this exercise, let's assume Star Industries' inventory looks like the following:

| Beginning inventory | 1000 units @$9 | =$9000.00 |

| Purchases | 9000 units @9 | =$81,000.00 |

| Sales | 6000 units @18 | =$108, 000.00 |

| Ending inventory | 4000 units @9 | =$36,000.00 |

At the beginning of this period, your inventory account will show a balance of $9,000, representing the 1000 units that you purchased at $9.

We then need to account for the purchase of 9,000 units.

This is accomplished with the following entry:

| Debt | Credit | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 06/09 | Inventory | 81,000 | |

| Accounts payable | 81,000 | ||

| Records the inventory purchase | |||

Each time you make a sale, it is recorded, however, note that there is no effect on the inventory account, as this is only recorded at the end of the period.

| Debt | Credit | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 06/09 | Accounts receivable | 108,000 | |

| Sales | 108,000 | ||

| Records the inventory sale | |||

Because of the nature of the inventory system, it is not until the end of the month that we can undertake a closing of the account. This account is closed by physically making the values in the account match the physical count of products left. It also closes the purchases account, and the difference between the two becomes the cost of goods sold.

In this case:

| Debit | Credit | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 30/9 | Inventory | 54,000 | |

| Cost of goods sold ($6,000 x $9) | 54,000 | ||

| Purchases ($9,000 x $9) | 81,000 | ||

| Closing account | 36,000 | ||

The closing inventory amount will be:

| Beginning inventory | $9,000 | |

| + | $81,000 | |

| $90,000 | ||

| Stock sold | - | $54,000 |

| $36,000 |

The accounting standard that governs inventory calculations is AASB 102 Inventories.

Creating well-defined processes helps standardise operations so payroll reporting can consistently be conducted in line with organisational and statutory. requirements. Training will also be far simpler, and staff can follow the same process every time. Streamlined business processes will also help eliminate errors, reduce waste and delays, and help organisations meet regulatory requirements.

Three main parties are involved in creating every process: the process owner, the team or users who will implement the process, and a process writer.

The process owner is responsible for outlining the purpose and goal of the process, along with defining the metrics for success.

The process owner tracks the performance of the process to determine whether it's succeeding or needs improvements. In addition, by tracking the process, the owner can identify issues as they arise.

It is up to the process owner to ensure staff completing the process meets the required standards. This means ensuring everyone is trained to follow the steps outlined in the documentation.

A process owner can enlist the help of the team or users who will implement the process, who are best placed to identify what is needed as they regularly employ it.

Users can also provide feedback as they use the process, which helps the owner understand its effectiveness. As users are on the frontline, they are usually the first to identify and report a problem.

A process writer can organise all the information about the process and document it in easy-to-follow steps. The writer is also responsible for editing documentation and updating it if processes change. Some organisations will employ a specialist technical writer experienced in business analysis and process writing; others will utilise existing staff members.

Explore the following steps to creating processes.

To start, you'll need to identify the processes you need to establish or improve, then write a brief description outlining their purpose and benefits. Creating a process from scratch may mean pinpointing routine tasks that your staff completes differently, which could result in inconsistent results.

The scope should define what the process will cover and what it won't. By outlining the scope of the processes, you set boundaries on what it will cover. That way, you're not overlapping into other operation areas and can measure the process's efficacy more accurately. Next, explain the impact the processes will have on other operations and any operations that may impact the process. Last, specify the limits of the process. For example, when does the process kick in, and when does it end? What signifies that the process is complete?

Process inputs are the resources that need to go into the processes to make them work. By understanding the inputs, you can measure how viable a process will be. You will know you have an effective process if the returns outweigh the inputs.

- Consider any physical resources that go into your processes. Such as raw materials, factories, components, and energy needed to run the machinery.

- Consider the labour you need, such as your workers, managers, or office support staff.

- Now, sum the financial resources needed to carry out the process. For example, how much does the equipment cost? What is the hourly rate of the staff involved? Have you factored in energy costs?

- Finally, ensure you account for the time that goes into the process.

The outputs are the outcomes that result from your processes. List everything produced by the process, both intentionally and unintentionally. It's important to include unintentional outputs as these may affect the viability of the process. As you list the outcomes, consider both physical returns, like the goods you produce and actions, like the movement of goods.

Before finalising the steps of your process, you need will to identify the requirements. Next, work with the people who will use the process and other affected stakeholders. Analyse the current situation and investigate any issues with how things work. Note down anything missing and any opportunities for improvement. You may also want to collect information on how existing operations work to understand where and when any issues occur. Finally, ensure you discuss potential solutions and visualise the process with the people who will use them. Research potential solutions to understand their feasibility and benchmark against others in the same industry for best practice solutions to the same scenarios. Also, investigate potential new technologies that could help streamline or automate processes.

Ensure you understand what needs to happen throughout the process to get the desired outcome. You may need to split the process into bite-size chunks. Then, for every bite-size chunk, probe into each step to work out the exact actions that will take place.

While a single person can carry out some processes, others may include whole teams or departments. Identifying who is involved with each step will help establish. The most practical course for the process. It also helps identify bottlenecks. Consider each task and its component and identify the individual, team, or department responsible for completing the process. Establish who will be responsible for documenting at each step and anyone who may have to approve certain activities.

When you have established what needs to be done and by whom, place those process tasks into a logical, sequential order. You will need to identify the inputs and outputs of each phase. At this stage, the input could be a new asset purchase. The output would be completing a new entry in the asset registry. Map where these outputs go and who they go to. To visualise, you could create a Supplier, Input, Process, Output, and Customer process map or (SIPOC). At each stage of the SIPOC, you will need to work out the following:

- Who provides the information or resource for this step?

- What info or resource (inputs) do they supply?

- What happens to this info or resource?

- What is the result (output) of this action?

- Who is it delivered to?

Digitising your processes lets you automate routing and automatically validate information to ensure everything is correct. Digitisation also enables stakeholders in your process to access information from anywhere, which is particularly helpful for distributed and remote teams.

Ensure all staff are on the same page and that processes are carried out in the same way by communicating the process and making it readily available. With all stages of the process documented, create instructions for staff to help them follow them. Ensure the documentation is easy to access and kept up-to-date. Remember to update process documentation whenever a change occurs and cascade this change to relevant staff. Communication must be two-way to keep processes running effectively. Build a system to help staff report issues and offer suggestions for improvement.

Tracking performance will enable you to identify bottlenecks or other issues immediately, which will help you implement any tweaks to the process. Establish the key metrics that enable you to track and schedule times to conduct reviews. Consider what the process is improving and how along with any unforeseen impacts that may be occurring.

Additional Reading

For more information about processes for payroll reporting, read the following:

Single Touch Payroll 2022, Ato.gov.au, viewed 4 November 2022

Employment and payroll records 2022, Ato.gov.au, viewed 4 November 2022

Answer the following three questions before moving on to the scenario-based tasks.

Scenario

Sandstone Sculptures of Sydney sold a bespoke sculpture installation to a private company that had just taken ownership of a building in a public square. They agreed on a deposit of $50,000 and the balance of $150,000 due within 90 days of delivery.

The business usually doesn’t sell on credit, so their books don't reflect provisions for bad debt, but they felt the financial risk of non-payment was worth it for the exposure of having their work displayed in such a prominent place, so they didn’t require the balance of payment before delivery — going against their usual practice of payment due before installation/delivery.

One year later, the public company folded, left the building, and the owners left the country. This is well and truly an uncollectable debt of $150,000.

As Sandstone's bookkeeper, use the forum to explain and justify which of the two methods you would use to record the bad debt portion of this sale. Please also include the journal entry to write off the bad debt.