In an early childhood service, we develop goals, strategies and plans to create an organised process for supporting children’s needs. For children who require further support, this means involving relevant stakeholders, such as external services, inclusion support agencies, internal inclusion support staff, families, the children themselves and, of course, the service staff.

We should consult the stakeholders as experts to continuously build knowledge on supporting the children most suitably.

By the end of this topic, you will understand the following:

- Strategies for respectful behaviours and inclusion

- Environments to support positive behaviour and inclusion

- Developing plans for behaviour and inclusion.

As mentioned in Topic 1, inclusion and behaviour supports do not happen statically or in isolation – they happen dynamically and by meaningful and purposeful action. Once we understand the needs of children, we must put in place collaborative strategies to support them.

It is well known that children learn best from peers and others who are more knowledgeable than them, so it is vital to support and educate their peers. Children promoting inclusion and embracing other children as unique individuals will significantly support the development of a successful inclusive program and society.

Reframing Behaviour and Needs

In understanding the capacities of each child, it is important to fully understand why and how reframing perception, attitudes and language regarding behaviours support the child. It helps to support children if you reframe your thinking by constantly considering, communicating and reflecting on the following:

- The child’s level of development, not their chronological age

- The child’s background and experiences and the influence these may have on the child

- Any diagnosis or developmental need and why it is present.

Reframing is a powerful thinking tool. It can help you to challenge your or others’ thinking, which can then motivate action. It is often helpful in examining perceived unfavourable behaviours and creating positive thinking.

Reframing is also an excellent tool for building and strengthening adult-child relationships, as it can allow the child to see themselves through the eyes of the adult, which is a positive thing once the behaviour has been reframed. We can see the link between reframing and strengths-based approaches in early childhood. Both are directed towards similar outcomes, though they are used in different practices.

The Six-Step Process of Reframing (Functional Assessment)

There are six key steps in a functional assessment or reframing; these include:

| 1 | Identify challenging behaviour | What is the child doing, and how is it affecting others? For example, the child actively avoids interactions with others. Also, identify the function the behaviour serves for the child and the usual outcomes, e.g., to assert needs and avoid all interaction. |

| 2 | Select observation strategies | Conduct observation across several different settings, e.g., mealtimes, play times, transition times or in small groups. When observing, consider how the program/environment/education and child ratios influence the child’s behaviour, e.g., challenging behaviour may occur most often when there is minimal supervision. |

| 3 | Identify the current explanation for the behaviour | What motivates the child? Use all information gathered and reflect on why the behaviour may occur. |

| 4 | Describe present corrective attempts: | Describe your responses and their effect on the child’s behaviour. Were they successful? |

| 5 | Generate a new explanation | Examine what is maintaining the behaviour rather than what might have triggered it, e.g., does it elicit a specific response from educators that reinforces it? |

| 6 | Change how you respond | Develop new ways to respond to the targeted behaviours that will result in positive changes in the child. |

Other Methods for Reframing

Many professionals and families reframe slightly differently. The following are basic reframing methods:

| Reframing action |

|

|---|---|

| Focus on the positive | Positive thinking is like a muscle that needs strengthening through practice. Try adjusting your thinking to focus on any positive aspects every time you notice yourself thinking negatively about a child because of their behaviour (which we know is counterproductive) or the behaviour itself. If something is difficult for a child, help them remember the success they had in the past. For example, if a child is struggling with a puzzle, you could say: ‘I know this puzzle is hard, but remember last week when you did all those puzzles in one day? That was amazing, and you were determined to complete them even though they were hard. When you were struggling before, you practised breathing in and out, so you didn’t get too frustrated, and it worked – do you remember that?’ Building self-esteem assists children with motivation, and motivation encourages children to build on their capacity and try new things. |

| Reframe the parents’ view of their child | It is necessary for families to strengthen their positive thinking and reframing abilities, as they can quickly become overwhelmed by their child’s struggles and behaviours, forgetting or overlooking the amazing qualities of the child. A typical example of this is labelling a child as opinionated instead of confident. |

| Combat resistance to change | As reframing is often a learnt thinking skill, you will likely have to remind yourself to implement the strategy continuously. Other stakeholders may also resist implementing the strategy, as it may not be understood or viewed as unnecessary. For example, some staff members may think children should do as they are told and should not be ‘babied’. Both educators and families must be reminded that reframing is an appropriate tool for use in the early years, but it is also a helpful strategy for any age. All children and adults can benefit from being reminded of their strengths and qualities when they are struggling or frustrated – it is a great way to refocus and ground a person. |

Educators as Child Advocates

Our actions as educators must include advocating for a child’s rights. It is essential to review the rights set out by the United Nations and Early Childhood Australia (ECA) and reflect on how you put these into practice as the advocate for children of the service.

Read

Read about some rights of children at the following link: Children’s Rights to Play from The Spoke

Early Childhood Australia (ECA) and Early Childhood Intervention Australia (ECIA) list the following principles for the inclusion of young children with a disability in early childhood education and care (ECEC):

- Best interests of the child: In all actions concerning children, the rights and best interests of the child are paramount, and young children’s healthy development, learning and well-being must be a priority for Australian society.

- Importance of families: Children’s growth and learning occur mainly in the context of their primary relationships in their families and partnerships between ECEC. [Supporting] professionals and families [is] essential.

- Social inclusion: Every child can make a unique contribution and participate in a wide range of activities and contexts as a family, community and society member.

- Diversity: Diversity and difference are valuable in their own right, as are the commonalities among people. Understanding families' practices, values, beliefs and cultures and acknowledging differences is fundamental.

- Equity: Equity requires that each child receives the support and resources needed to participate, engage and succeed.

High expectations for every child: All children can succeed, regardless of diverse circumstances and abilities. Children progress well when they, their families, early childhood educators and support professionals have high expectations for their achievement in learning and development.

Evidence-based practice: In Early childhood programs, this is informed by the knowledge and experience of educators and families and current research findings.10

Read

- You can read the complete statement regarding the inclusion of children with disabilities at the following link: Position Statement on the Inclusion of Children With a Disability in Early Childhood Education and Care by ECA and ECIA

- Visit the following link to read about how you can be a culturally sensitive educator: 30 Ways to Become a Culturally Sensitive Educator from InformED

Grounding, Meditation and Mindfulness Exercises

Meditation aims to reground, recentre, refocus and calm. It helps a person be in the moment. You will find it challenging to help a child do this if you are not calm and focused, so you need to learn the exercises discussed in this section to achieve the desired state.

Meditation is a simple technique but can be challenging for many because the fast-paced and demanding nature of the modern world does not train us to be present and mindful.

You can meditate using various techniques, including yoga, reflection, gratitude exercises, guided or unguided meditation with music or without, and object focus. Meditation can be helpful for educators and children, as well as children’s families.

Watch

Sleep Meditation for Kids The Sleepy Kangaroo Bedtime Story for Kids by Happy Minds - Sleep Meditation & Bedtime Stories.

Yoga

Yoga encompasses elements of physical, mental and spiritual practices to gain ultimate health and well-being by building strength, awareness and harmony of the mind and body – it also supports the concept of ‘being’ and being in the moment through refocusing and grounding.

Watch

Watch these videos for guided yoga sessions that can be useful for children:

- Kids Yoga Practice by Gaiam Australia.

Cosmic Kids Yoga shows examples of yoga practices targeted at children.

Mindfulness

Mindfulness exercises are all flexible to the child's needs, interests and skills. The main goal is for the children to practise being in the moment and focusing on something to become calm and focused.

Watch

Watch these videos to learn about mindfulness meditation:

- Mindfulness and how the brain works by Smiling Minds.

- What is Mindfulness? by Smiling Mind.

Mindfulness Exercises

Try a mindfulness exercise. Look around you and identify the following:

Sight:

- Five colours that you can see

- Four shapes that you can see

- Three soft things that you can see

- Two people that you can see

- One book (toy or another item) that you can see.

Other senses:

- Four things that you can hear

- Three things that you can hear

- Two things that you can touch.

Ensure that you keep notes for future reference, as this information will support your assessments and professional practice.

ABC Around the Room

Older children can name objects around the room, starting with each letter of the alphabet, beginning with ‘A’. This helps them focus, self-regulate and ground themselves.

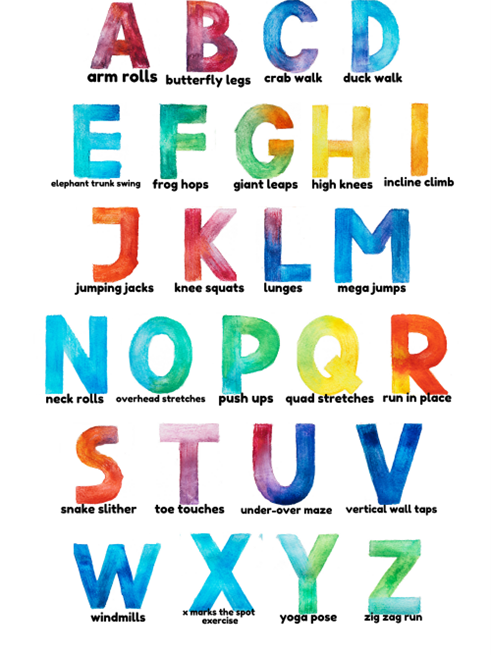

You could also get the children to partake in ‘alphabet exercises’, where you run through the alphabet and do exercises that begin with each letter. It is a fun way to get the children moving and burning off excess energy, helping to calm and focus their brains.

Alphabet Exercise11

Being Connected to the Ground

Children can pretend to be anything that connects to the ground—the more connected, the better. For example, they could pretend to be trees, rocks or pieces of seaweed. This connection to the room and ground helps children to connect with their body, becoming more grounded through feeling ‘at one’ with themselves, their body and the room.

An educator can help to guide the children in the activity by talking them through points of focus and feeling.

For example: ‘Feel the connection between you and the ground. You are a tree. You are firmly planted. You feel your feet rooted to the ground. Your back is a strong trunk, helping you feel stable. You feel your toes connecting with the ground. Your arms are your branches. You feel them reach out into the world.’

This technique can be used with younger and older children.

Focus on an Object

Training yourself to focus on an object is a mindfulness technique that can help to calm the mind and bring you into the present moment. To engage in object focus, hold an object in your hand and focus on it:

- Notice its features, colours and textures.

- Consider how the object feels when you run your fingers over or squeeze it and notice the colours you can see.

- Try to identify every feature of the item.

This is an exercise that can be done anywhere. You can utilise any object, preferably a unique object, with unique textures, patterns and colours, such as snow globes, faux fur or colourful rocks.

Hug Affirmations

Hugs utilise the grounding power of physical pressure on the body. You can combine hugging with positive self-affirmations for a powerful, calming, and confidence-boosting effect. The following steps demonstrate how you engage in hug affirmations:

- Use your right hand to tap your left shoulder

- Use your left hand to tap your right shoulder

- State a positive affirmation out loud

- Hug yourself

- Repeat for as long as needed

Affirmations may be words of encouragement such as ‘I can do this’ or ‘I am in control’.

Breathing Exercises

Breathing exercises effectively support all the previously listed skills and exercises to reground, refocus and calm. Controlling the breath is a power method to calm the central nervous system and assist the body in coming into a state of calm.

Watch

There are many breathing exercises you can use. Included here are two you may like to try:

- Guided Square Breathing for Children by Learn and Play Right Brain Education

- Five Finger Breath by Learning Tree Yoga

Practice

Reframing Behaviour

Review the scenarios in Learning Activity 1J and 1M:

- Consider how you would reframe the behaviours of:

- The child

- The parent

- Consider a meditation style that might work for each child, and explain why you think this style would work for the particular child? (Consider each child physiologically and psychologically.)

Ensure that you keep notes for future reference, as this information will support your assessments and professional practice.

Read

Read about different types of meditation from headspace on the Types of Meditation.

Watch

Watch these videos to learn about types of meditation and meditation for children:

- Kindness: How to Be Nicer to Yourself by Headspace.

- Guided Meditation for Children | Your Secret Treehouse | Relaxation for Kids by New Horizon - Meditation and Sleep Stories.

Supporting Self-Regulation

Babies can not self-regulate their behaviour and will demand the comfort of a significant carer to support regulation. As we learn to do so, as we develop, observe and experience our environment and observe our role models, we begin to build skills to self-regulate. We learn to settle ourselves when we understand we are safe and will have our needs met.

Babies who have not been nurtured or had consistent care do not learn to self-settle and will continue to cry because they do not know if their needs will be met. In cases of severe neglect, babies may stop crying altogether because they know no one will tend to their needs.

Children learn to self-regulate their emotions over time, but all will need support to learn to do this. Self-regulation requires a child to understand, manage and take control of their own emotions so they do not negatively impact their life, learning and friendships.

Learning to self-regulate happens within a developmental level but begins in young infants. Infants often learn to settle by sucking on their fingers for comfort and stop crying when their needs are met. Having nurturing and responsive adults in a child’s life are the first step to developing self-regulation. Some children, however, for various reasons, find regulating themselves more difficult than others.

Children need to learn to self-regulate so they can:

- Calm themselves if they get excited, scared or upset; or experience unexpected change or new people, places or objects

- Focus on a task

- Control impulses

- Learn social behaviours to form relationships

- Become more independent

- Manage stress.

Read

Read more on self-regulation at the following link: Quality Area 5: Supporting Children to Regulate Their Own Behaviour from the ACECQA.

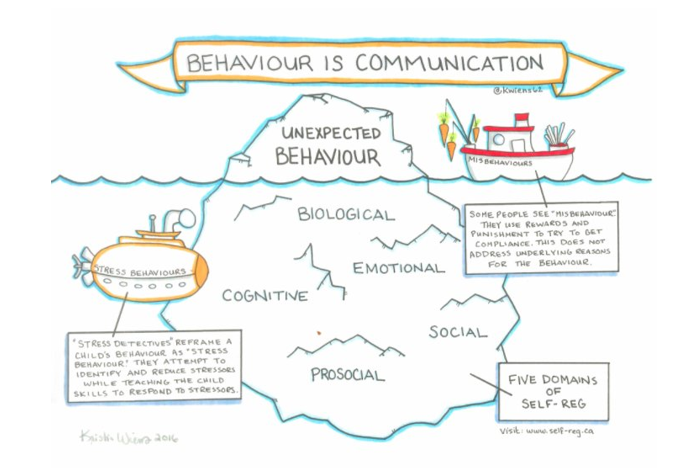

Domains of Self-Regulation

Dr Stuart Shanker, a research professor emeritus of philosophy and psychology, developed Self-Reg, a self-regulation method that incorporates five domains. It is a process that all ages can use. The process covers the following:

The five domains to consider concerning self-regulation are:

- Biological

- Emotion

- Cognitive

- Social

- Pro-social

Biological

Regulation is necessary for optimal brain development – educators need to understand the impact on the brain, especially the impacts that occur through regular and extensive flight-fight-or-freeze reactions. Educators can support a child to upregulate or downregulate to find optimal levels of regulation.

A loss of resilience occurs when children experience an overwhelmed central nervous system. It is important to support a child in developing self-regulation, noting that adults support regulation until they can self-regulate independently. Educators and families can impact a child’s behaviour by providing positive behaviour responses and sensitive, consistent and responsive caregiving and attachments.

Without the development of self-regulation, a child can suffer from lifelong adverse effects on their physical and mental health.

There are six stages of arousal in the self-regulation arousal states by Shanker and are:

The reaction is a child commences with activation, which occurs when there is stress causing excess fuel/energy in the child – hyper-arousal:

- Fight, Flight or Flooded (or freeze) occurs when the excess energy causes the child to be excited or upset to the point of running away, lashing out verbally or physically, or tears

- Hyperalert is a state where the child is very excited, angry or upset

- Alert is when the child is calm enough to be focused

- Hypo-alert is when the child is feeling zoned out, too tired to think clearly

- Drowsy occurs when the child is almost asleep

- Asleep

After the response, the child will need to recover.

How much activation or recovery is necessary for any particular task changes for each child and from situation to situation. Educators can recognise the child’s arousal state so they can adjust through up-regulating or down-regulating their behaviour to support optimal regulation.

Emotion Domain

The emotional domain covers how a child learns to monitor, evaluate and modify their emotions. Parents and early childhood educators must soothe a child before they try to educate them, as children struggle to learn in an overly emotional state.

Adults should follow the three Rs:

- Recognise – Recognise the signs of escalating stress.

- Reduce – Identify and reduce or eliminate the stressor if possible. Monitor, evaluate and modify the child’s emotions.

- Restore – Restore the child's energy and resume the task at hand.

Cognitive Domain

The cognitive domain refers to the child’s ability to acknowledge and process sensory information, both internal and external. Sustained concentration requires energy and demand on the nervous system, which can deplete energy levels needed for self-regulation. Adults need to be mindful of providing too much of a challenge for this reason instead of considering the zone of proximal development (ZPD).

When too much energy is used, it minimises attention, hence the motivation for learning.

The zone of proximal development refers to the difference between what a learner can do without help and what he or she can achieve with guidance and encouragement from a skilled partner. Thus, the term ‘proximal’ refers to those skills that the learner is ‘close’ to mastering.13 Dr Saul McLeod, Simply Psychology

Social Domain

When the arousal systems are stressed, children can find it difficult to manage their feelings and have the energy to engage socially. This is not due to a lack of motivation but simply an inability to overcome challenges. Children must be soothed and shown that the world is safe and supportive before they can engage socially again.

Pro-social Domain

Children are biologically geared towards social interactions and, generally, show empathy and care towards others. When a child is acting in an anti-social way, they may be overwhelmed or stressed. Once a child experiences a stress overload, they activate the flight or fight response. This stress overload works to shut down systems that generate “cognitive empathy”, where children cease to be affected by and aware of what someone else feels. Educators can support self-reg by not blaming a child for their lack of empathy and providing soothing to avoid escalating when the child needs to down-regulate. When a child experiences a fight-flight-or-freeze response, the systems that enable the child to feel cognitive empathy, which is the ability to imagine yourself ‘in someone else’s shoes’, and affective empathy, which is the ability to feel what someone else feels, shut down.

When a child feels threatened, the result can be sympathetic flooding (anger and aggression, flight or desertion) or parasympathetic flooding (withdrawal, paralysis). Such dysregulation can have a profound effect on her tension, emotions, and self-awareness.14

Read

Read more about the five domains of Self-Reg at the following link: Self-Regulation: 5 Domains of Self-Reg from The MEHRIT Centre

Building an environment that caters to the development and needs of children is imperative. Consider the areas that may cause children to feel overwhelmed, anxious, distracted, discomfort, frustrated, etc. The service needs to ensure environments are organised, represent the children and suit their needs physically and academically, modifying the environment for children with physical disabilities (e.g. opening spaces for access and changing the height of surfaces) and creating sensory or visual cues or tactile markers for those who need them.

A helpful strategy to assess whether a space is suitable is to sit yourself at the level of the children (around their height) and discover what you can see, what you cannot see, what you can access, what feels crowded or causes visual crowding, and what makes the environment feel ‘too busy’.

Be aware of how the children respond to the environment and ensure there are spaces for solitude and quiet when needed. You may also become aware of the need for sensory toys and items to comfort certain children. Track triggers, and if practical, make environmental alterations as required.

When assessing the environment, consider the following questions:

- How is each child represented in this environment?

- Is the environment cluttered and unorganised?

- How am I, as the educator, meeting their individual needs within the environment?

- Are there any areas the child finds overwhelming or challenging?

- How do they interact with others in the environment?

- When do they typically need breaks?

- How are the children reacting to the environment?

- Where do they engage or disengage from the program?

- Are there specific areas where social conflict occurs? If so, why?

- Do I have enough support as the educator (e.g. enough staff/educators [meeting educator–child ratios], enough education on a topic, enough support from the service or external professionals)?

Explore

Review this resource to see a series of videos that teach you some of the best approaches to conducting inclusive teaching: Supporting Every Teacher: Ten Top Approaches to Inclusive Teaching and Learning – Part Two from Cambridge University Press:

Watch

View these clips to learn about inclusion in early childhood:

- Meaningful Inclusion in Early Childhood by WisconsinDPI

- Creating an Inclusive Setting by AllPlay

Note

Tips for supporting inclusion:

- Know the child’s interests.

- Give time for lots of practice.

- Consider and reflect on alternative strategies for instruction and learning.

- Ensure materials are adapted to suit factors such as grip strength, mobility and coordination.

- Engage children in visual stimuli and active learning.

- Provide emotionally and physically safe environments.

- Increase sense of belonging.

Watch

Watch these videos to see how children with a visual impairment can be supported and learn to engage in a service program:

- Understanding Vision Impairment in Children - Lily-Grace by RNIB

- Learning Braille With Jessica and Isabella by RNIB:

Define Behaviours

Before you can instruct children on how to behave, you must first define the target behaviour. What do you want to achieve, and what strategies can you use? You may also reflect on why these behaviours are deemed necessary, who has advised on the behaviours and how the behaviours benefit the child.

Defined behaviours should be:

- Observable

- Measurable

- Specific.

The ABC approach, discussed in section 2.3., is commonly used to define behaviour goals. However, some services may also use SMART goals.

SMART Goals for Kids

- Specific: What do you want to accomplish? Goals should be clear and detailed. Make sure it's not too general.

- Measurable: How will you know when you reach your goal? You should be able to track your progress and know when you accomplish it.

- Achievable: What steps will you need to take the achieve the goal? List steps.

- Realistic: Is the goal realistic? Make sure your goal is not too easy or hard.

- Time-bound: When will you do this? Set a deadline for your goal. Think about short term (few weeks or month) vs long-term goals (months or a year).

Expectations and Routines

There are various things educators can do to ensure routines run smoothly and expectations are met:

- Make expectations and routines in the environment clear and consistent, as well as age and developmentally-appropriate.

- Give individual instructions to a child – do not shout from across the room or give too many instructions at once – try giving one instruction at a time and build from there.

- Give options for when expectations cannot be met (e.g. the child wants to throw a toy car inside – they can be offered the option of throwing a ball outside).

This technique follows ACT guidelines:

- Acknowledge

- Communicate

- Target

Educators can acknowledge the need or desire, communicate the expectation for the behaviour and target acceptable alternative behaviours.

All feelings, desires and wishes of the child are accepted, but not all behaviours are acceptable16.

These guidelines are based on therapeutic limit setting but can be easily used by educators in early childhood education services.

Watch

Watch this video to learn about limit setting: ACT Limit Setting by Jigsaw4u Merton & Sutton.

Collaborate with external support agencies and families to ensure expectations and methods are similar and that you are all working towards the same goals.

Consider how children will learn expectations and routines. You could employ any of the following methods:

Social Stories

Social stories describe social situations and set out the behaviours or responses that are appropriate for the situation. They are used for children to learn new or acceptable behaviours and appropriate social responses. Social stories are particularly useful for children with autism or other children with learning or intellectual disorders.

Read

- To learn about social stories, visit the following link: Social Stories from the Early Childhood Learning and Knowledge Center.

- You can find templates for social stories at the following link: Starting Preschool Social Stories from the New South Wales Government Department of Education.

Explore

To see examples of social stories, visit the following link: Early Stories from AllPlay Learn.

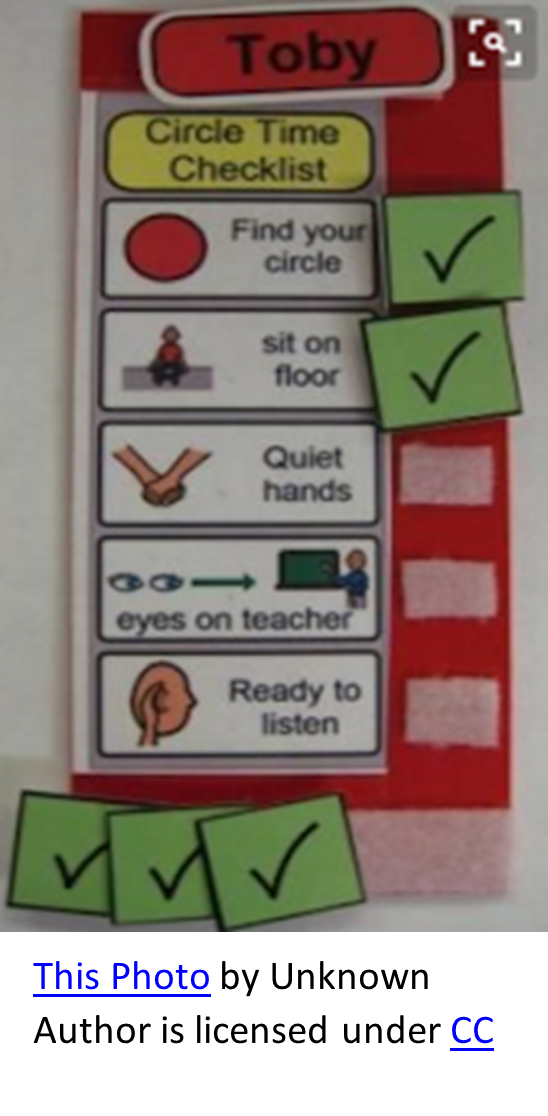

Visual Prompts and Cues

Visual prompts, which are visual communication techniques, support children in knowing what is expected of them. They are often used for children who cannot read, require more consistency and transition assurance (preparation), or as a quick visual reference.

Visual supports and cues present information using symbols, photographs, written words and objects. These are especially useful for children with disabilities or from a different culture. For example, they can set out a timetable of the day's activities to support a child in predicting what is about to occur.

Explore

You can find examples of visual cues at:

Assistive Technologies

Technology can support children with disabilities to communicate and engage in educational content, helping them to participate in the program. These technologies are specific to the child and are usually assessed and provided by an occupational therapist, speech therapist or assistive technology specialist.

Read

Read about assistive technology at Assistive Technology for Children With Disabilities: Creating Opportunities for Education, Inclusion and Participation by the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) and the World Health Organization.

Songs

Songs can be used as a way to help children remember routines and what they learn. They can be much more fun and easier to recall than requests and routines expressed through normal speech. In addition, educators may use ‘good morning’ songs to support the daily transition into the program and instil a sense of belonging and focus.

For example, an educator can use a ‘good morning’ song (to the tune of ‘Happy Birthday’):

- Good morning to you,

- Good morning to you,

- Good morning everybody,

- Good morning to you.

- Are you [insert any feeling or adjectives] today?

- Are you good [insert any feeling or adjectives] today?

- Good morning everybody,

- Good morning to you.

Explore

For more songs you can use with children, visit 10 Preschool Transitions – Songs and Chants to Help Your Day Run Smoothly from Teaching Mama

Watch

These videos feature songs that support routines and recognise emotion and body awareness:

- This Is the Way by Super Simple Songs – Kids Songs

- If You Are Happy and You Know It Clap Your Hands (With Lyrics) by EflashApps

- Head Shoulders Knees & Toes (Sing It) by Super Simple Songs – Kids Songs

Verbal Reminders

Verbal reminders of expectations need to be clear, consistent and concise so children can easily understand them:

- Use as few words as possible and be age appropriate.

- Cooperation is more likely when expectations are repeated consistently, as the child will know and remember what is expected of them.

Assisting the child in meeting the expectation, to begin with, or at times when they require support, will present a verbal and physical example of the expectation. Clarify any misunderstandings and provide explanations of why these expectations are required.

Remember, when building and maintaining expectations, you must consider how you communicate: ensure you are calm and aware of your tone, volume and mannerisms, and body language.

Problem-Solving Questions and Redirection

Remember, language needs to be straightforward, but no one wants to be managed or directed all the time – this removes a child’s sense of control and agency. Using problem-solving questions to ask children about expectations they already know is an excellent way to give them control while redirecting their behaviours.

Example

- (Child finishes going to the toilet.)

- Educator: What do we need to do after going to the toilet?

- Child: Flush the toilet, then wash and dry our hands.

- Educator: And why do we do that?

- Child: To keep ourselves and others clean!

Understanding why people are expected to follow particular rules or do certain tasks is always beneficial. Even as an adult, if someone asks you to do something, it would likely be important to understand why you should do it. Knowing the reasoning behind a task is motivating for children (as well as adults).

This can be considered redirection, as can supporting children to ‘re-engage’ in the program. Children often demonstrate inappropriate behaviours when disengaged, so being aware of children who look disengaged is important. Finding an activity they can enjoy with you can minimise disruptions for children.

Asking them to assist you in setting up an activity or routine or asking them if they have an idea of what they would like to do can help re-engage them in the program.

Children do not always have to be heavily engaged, however. Sometimes they need downtime, sitting in a tent or on cushions, relaxing, reading a book, cuddling or listening to an audio track.

There are some engaging educational podcasts for children, so having a space with headphones and some pillows can benefit children who need to decompress.

Watch

Watch how the teacher in this video uses problem-solving questions to reinforce and remind about expectations: Getting Behaviour Back on Track by Responsive Classroom.

Educator Supervision and Positioning

For many reasons, there will be times when educators need to be alert to the behaviours of children. For example, a child may be engaging in inappropriate behaviour that has the potential to harm others or themselves.

Educators must consider where they position themselves around the room to ensure supervision requirements are always met. Active supervisors should place themselves where they will be most needed. They may need to be close to children who require support to engage in the program.

Educators must observe for signs of need but should not intervene too quickly. There is a delicate balance between avoiding serious conflict and frustration and ensuring that children can practise skills without premature interference.

By listening and watching closely, educators should also be able to anticipate some behaviours from their knowledge of the child:

- What frustrates the child

- The facial expressions and changes in voice the child tends to demonstrate when they feel a certain way

- What triggers the child’s emotions

Read

To learn more about active supervision, read the following information:

Role Modelling

Educators have a crucial role, and many do not realise the impact they have on the children in their care. Children mimic what they see from those around them, especially adults. Educators should be confident in modelling the following:

- Emotions (share with children that you have emotions too)

- Strategies for handling emotions

- How to treat and celebrate others

- How to celebrate and acknowledge the positive behaviours of others

- How to communicate understanding and empathy with others

- How to support others with strategies that might help them deal with challenging times.

Example

This is an example conversation of an educator modelling how to handle accidentally making a mess:

- Educator: Oh no! I’m so frustrated that this paint spilt on the floor. (Educator takes a deep breath.) It’s okay. It’s only paint. We can clean it up. Will you help me?

- Child: Okay, I will help!

- Educator: You will? You are so kind to help me!

Supporting Agency and Independence

Children of all ages can make certain decisions and develop their independence differently; it is essential to encourage and build on this motivation. Supporting agency and independence also empowers children and helps to advance self-regulation skills, as they have more control and are better prepared for challenges they may face.

Supporting Relationships With Peers

Providing lots of opportunities for children to engage with their peers can not only assist their learning but allow them to observe how other children show interest and socialise with each other. Many children will not always find social interactions easy for many reasons, including having challenges with:

- Understanding theory of mind (what others might be thinking or feeling and the needs of others) or empathy

- Their developmental stage (they may be very much within the egocentric stage or be linguistically delayed)

- Understanding social cues

- Activities where children get to know each other (such as sharing information about their family and likes verbally or visually).

Play experiences that can support social competence and relationships include:

- Imitation games (e.g. copying each other, shadow or mirror games)

- Embodiment games (e.g. games that involve holding hands in a circle and following instructions [such as when playing Simon Says])

- No-touch games children can play together (e.g. blowing bubbles, throwing and catching a ball, hula hooping).

Explore

More ideas for no-touch games ideas can be found at the following link: 8 No-Touch Group Games Kids Can Play Together from Active for Life.

Transition Reminders

Provide countdowns whenever possible to prepare children for an upcoming transition. For example, let them know a transition is coming by alerting them 10 minutes, then five minutes, then two minutes before the change – make sure you do then follow through with the transition. It can also be beneficial to provide a warning when something the children are enjoying is coming to an end.

Supporting Behaviour

Providing developmentally appropriate guidelines and expectations is paramount. If the child is incapable of meeting behavioural expectations (e.g. expecting a one-year-old to share), there will always be frustration. Therefore, educators need to ensure children have an understanding of behaviour expectations. As explained previously, this can be achieved using various sensory resources and stimuli.

One-word expectations or character virtues are a great way to begin conversations about expectations. For example, educators can communicate the value of being ‘gentle’, demonstrate what being gentle looks like and praise children for gentle behaviour. Educators should ensure the child understands they are being praised – you may include non-verbal communication, such as giving a thumbs up and a big smile.

Behaviour guidance is an integral part of educational programs, linked to the outcomes of the National Quality Framework:

- The child will have a strong sense of identity.

- The child will be connected with and contribute to their world.

- The child will have a strong sense of well-being.

- The child will be a confident and involved learner.

- The child will be an effective communicator.

Behaviour guidance should occur daily through positive, sensitive and nurturing interaction and communication, monitoring challenging behaviours and triggers, reducing unwanted behaviours and encouraging children to build self-esteem and achieve success and competence.

Developmental milestones provide good knowledge of typical expectations of behaviour comprehension and abilities. For more on developmental milestones, revisit Early Years Learning Framework Practice-Based Resources .

Explore

Learn about understanding behaviour at the following link: Understanding Children’s Behaviour from the Victoria State Government (Vic) Department of Education and Training.

Supporting Children to Manage Problems and Conflict

Develop visual strategies consistently implemented when developmentally appropriate to help children manage their problems. An even better strategy is to manage problems together with the child.

Encouraging respectful behaviours is contagious. If children learn to praise each other for their kindness, gentleness and patience, they will also learn when other children are not practising these behaviours. Children reminding each other about expectations and promoting prosocial behaviours often generate better results than any adult trying to encourage these things.

Creating a Strategy Together

By around three to four years old, many children can manage situations themselves as long as they have guidelines. They do not always need adult intervention to manage conflict, disagreements or problems. Allowing children to manage what they can build a sense of agency and ownership within the group.

Read

At the following link, you can find a guide to problem-solving for children: Problem Solving Guide from AllPlay Learn.

Practice

Problem Solving Guide

The Little.ly Early Learning Centre has just employed you in their 3-4-year-old room. Create a problem-solving guide that you can use with the children for this room. Your aim is to develop a guide to support children to be active problem solvers.

Ensure that you keep notes for future reference, as this information will support your assessments and professional practice.

Read

Review these posters that promote inclusion and strategies for peers:

Educators must collaborate with relevant professionals and families to design a plan for the service. Often it may be an amalgamated version of what an external service has devised, especially regarding goals and strategies.

A plan for working together should be developed if visits with external providers, such as therapists, are conducted at the service. An inclusion support plan will typically include the following details:

- The child’s name and date of birth

- The start date of the plan and review dates/points

- Goals with strategies

- Barriers

- External and internal support personnel

- Resources/material requirements

- Links to the curriculum and the National Quality

- Standard

- Educator reflections on the child and the child’s strengths

- Amendments, modifications and alterations

An early childhood services plan will also include the relevant practices, principles and outcomes related to the program in which the child is enrolled. Consider the pedagogy and models you will utilise for the inclusion of all children, always considering alternative and open-minded approaches to meeting the needs of children.

Developing plans for behaviours of concern includes the following steps:

Explore

Visit these links to learn about SIP:

- Inclusion Support Program – Barriers and Strategies from the Australian Government Department of Education

- Strategic Inclusion Plan Form from the Australian Government Department of Education

- Strategic Inclusion Plans from KU Children’s Services

A SIP is a self-guided inclusion assessment and planning tool for services that includes strategies for improving and embedding inclusive practice in line with the National Quality Standards (NQS). The development of a SIP recognises the current inclusive capacity of a service and outlines the strategies and actions educators will implement to increase this capacity to include all children.

The development of a SIP is the first step to accessing support from the ISP, including funding through the Inclusion Development Fund (IDF).17

Analysing Information Regarding Identified Behaviour

To determine the role of, and the meaning behind, behaviour, analyse the information you’ve gathered. Use the baseline of occurrence to determine the most appropriate strategies to support a child using positive approaches to meet their needs.

One method to collect evidence is observation. Observations provide recorded data that gives insight into the behaviour's frequency, intensity, and reasons. Other evidence sources can include:

- Observation notes and behaviour recording charts

- Children’s records and profile

- Cultural and family background

- Interviewing families and others

- Medical reports

- Functional assessments

- Incident reports.

Collaborative approach

The same collaborative approach used to gather information is used when analysing evidence. Collaboration enables a comprehensive picture of the child’s background and temperament to understand their needs better. Collaboration will occur with the following groups:

- Families

- Educators

- The child

- Medical practitioners and allied health professionals as needed.

Analysis

All components of gathered evidence are analysed to identify how they relate for better understanding. The analysis contributes to evidence-based decisions to best support the behaviour being used by the child.

Analysed evidence can then be used to develop behaviour support plans based on respectful relationships with warm, responsive and available educators according to the NQS, service philosophy and service policies and procedures.

Consider the following questions when analysing gathered evidence:

- What is happening in the child’s family situation?

- Does the behaviour include a cultural element?

- Are there health/developmental issues requiring resolution?

- Does the behaviour occur during the same or similar activities or at the same times?

- Who is present most of the time when the behaviour occurs?

The analysis looks beyond the child’s immediate behaviour and considers the genuine relationship needs that need to be met. If, for example, the behaviour arose because a child becomes overwhelmed, support may include an educator making eye contact to connect and coming down to their level. Then they can soothe, providing a safe place for the child to be away from the stress and calm down. This could be classified as a support strategy in the plan.

Analysis may reveal that the behaviours are stress responses instead of acting out. Therefore, it is valuable to reframe behaviour by answering, “Why am I seeing this behaviour now?” Then, focus on the domain where the stress originates (biological, emotional, cognitive, social, prosocial—or a combination).

Behaviour may be due to an inability to react appropriately to everyday events, such as pushing a child away instead of saying, “go away”. Supports may encourage a child to use various options to express their needs and feelings, thereby developing resilience to managing stressors. Children will develop resilience when they have a positive and supportive network. Assisting children to be confident in their strengths and abilities and supporting them in building self-regulation skills are keys to building resilient children.

The aim is to develop a child’s self-regulation, positive self-image and self-esteem. Building skill is an incremental process that develops gradually over time and on a continuum. Approach the behaviour from a strength-based perspective, where the child is seen as capable. Encourage a sense of identity, pride and respect by acknowledging polite behaviour and modelling empathy.

Using a chart ensures all elements are examined during analysis, allowing a systematic approach to reviewing behaviour and gathering evidence.

Identifying Long- and Short-Term Goals

Once you’ve analysed the information you’ve gathered, you can identify goals for the child that outline the desired future state for the child. They must be developed in consultation with others, so they are sensitive to and consistent with the child’s cultural practices, abilities, age and stage of development.

Goal setting includes long- and short-term goals focusing on a range of outcomes for the child, including support, routine management, learning opportunities and skill-building or relationships focus.

Long-term goals take longer to achieve and may require more time, planning and resources.Short-term goals are more immediate and can be implemented quickly. They can be seen as actionable steps towards a more future-focused long-term goal. Objectives in the plan become achievable steps taken to reach the agreed goals. In deciding which ones to achieve first, it is essential to prioritise. A child can easily be overwhelmed if too many objectives are focused on simultaneously. It is better to achieve small incremental steps rather than aiming too big at the start. Once some victories have been achieved, the next objective can be introduced.

Use the S.M.A.R.T goals techniques when developing goals. This will ensure that all elements are considered and that goals can be implemented and reviewed against explicit criteria.

Liaising With Professionals and Authorities

It may be necessary to use external services and professional assistance to meet the particular needs of children beyond the service’s expertise or need specialised interventions and advice. In addition, various resources and supports can help identify how to handle better complex situations arising from children’s behaviours.

Referring to a Professional

A child may benefit from additional help from professional providers when they are not developing within the normal range, or a need hinders their engagement in the service or their learning, such as:

- Significant delay in developmental milestones

- Developmental delays in motor skills

- Hearing difficulties, and delayed speech

- Intense or frequent behaviours requiring specialised supports

- The child and family aren’t coping.

Services could include:

- Early intervention

- Educational psychologists

- Speech therapists

- Behavioural psychologists

- Occupational therapists

- Medical practitioners

- Physiotherapists.

Follow your service’s procedures before engaging or referring to a specialist service. These may include the following steps:

- Discuss identified needs with the supervisor – don’t act on your own; follow your service’s requirements and seek approval; once approved by the supervisor, they could involve the family

- Discuss needs identified with colleagues and family ( if permitted)

- Provide background information about the service for the family

- Once approved, help the family to refer to the program.

The professional service may seek background information about the behaviour of concern. Any information sharing must comply with privacy and confidentiality considerations and the family’s consent.

Referring to Authorities

Where more severe concerns are identified, it is necessary to refer to the authorities. A report to the child protection authorities must be made when there are indicators of a risk of harm or a child has been harmed. This is called mandatory reporting and comes under the area of child protection. Services must ensure that children’s well-being is protected and that they are free from physical, social and emotional abuse or neglect. Services must:

- Follow Regulation 86 of the Education and Care Services National Regulations (2011)

- Follow the legislative requirements for their state and territory

- Maintain awareness of the current child protection law and any obligations educators and other employees have under it in their state or territory.

Referral to authorities occurs when the service has identified:

- Risk of abuse or neglect for the child

- Serious family dispute

A child will not always say or verbally disclose that they have been abused. Instead, children can use challenging or oppositional behaviours to communicate when something is occurring to them. Such behaviours can include:

- Noticeable aggression, acting out or extreme passivity

- Obvious changes in behaviour

- Increased anxiety and distress

- Increased and unexplained crying

- Withdrawn or anxious presentation

- Being abusive or sexually provocative during play/activities

- Habit disorders such as rocking, sucking

- Parentified behaviours (takings on roles and responsibilities as if they are a parent)

- Fear of going home, avoidance of going home or running away

- Fear of a caregiver or parent.

Services that can receive a notification of a risk of abuse or actual abuse include:

- Police – call 000 in an emergency or the police assistance line on 131 444 for non-urgent assistance

- Children’s protective services, e.g., DOCS, Child Safety, Department of Child Safety.

Practice

Child Protection Authorities

- Conduct some research into the child protection agencies in your state or territory.

- Conduct research into the legislation and regulations for early childhood services related to services requirements to report children at risk of harm or abuse. Record your findings.

- Ensure that you keep notes for future reference, as this information will support your assessments and professional practice.

You must follow your service’s policies and procedures for managing the risk of abuse and mandatory reporting. The first step is to discuss the circumstances with your supervisor to determine the level of urgency and agree on who will make the report/referral and to whom.

Consider the following questions, suggested by the Royal Commission into child abuse, when determining whether intervention is required:

- Does this happen too frequently?

- Does this seem unusual?

- Does this make me uneasy or worried for the child?

- Has anyone else noticed or commented?

- If I suspect a child is at risk, what should I do?

Case Study

Scenario 1Situation: During circle time, a 4-year-old boy, Alex, shares that his older sibling often “hits him when he’s angry” and feels scared to go home. He shows signs of distress and has unexplained bruises on his arms. When the teacher gently asks for more details, Alex becomes withdrawn and says, “It happens all the time.” Action Required: The educator must report this information to the appropriate authorities, as it indicates potential physical abuse and places Alex’s safety at risk. |

Scenario 2Situation: A 5-year-old girl, Mia, comes to school with unkempt hair, dirty clothes, and a strong odour. During lunch, she mentions that she often goes to bed hungry and doesn’t have enough food at home. She appears lethargic and struggles to participate in activities. Action Required: The educator must report this situation to authorities, as it suggests possible neglect and poses a risk to Mia’s well-being. |

Scenario 3Situation: During a group art activity, a 3-year-old boy, Leo, becomes frustrated when his painting doesn’t turn out the way he envisioned. He cries for a moment but then takes a deep breath, asks for help from an educator, and tries. Action: This scenario reflects normal behaviour, demonstrating typical emotional responses to frustration and resilience. No reporting is necessary, as Leo is engaging in healthy emotional expression and problem-solving. |

Using these scenarios, refer to your state's reporting guidelines to assess whether reporting is required. You can use the NSW Mandatory Reporter Guide as a reference for this process.

Developing and Documenting the Plan

Developing and documenting behaviour support plans uses the gathered evidence to determine the goals and programs to support appropriate behaviours. The plan intends to guide behaviour and achieve learning outcomes in children and align with the National Quality Standards (NQS), Quality Area 5 – Relationships with Children. The plan will use observations gained and analysed to develop evidence-based options to suit the child's needs.

Plans should be documented using positive guidance and behaviour management strategies. They should set out ways to work with children that support behaviours appropriately. Strategies must ensure that behaviour support techniques do not include physical harm, verbal or emotional punishment or withholding freedom. The intent is to develop positive learning outcomes.

Plans should be:

- In writing

- Be written clearly, and without ambiguity so everyone can easily follow them

- Uses language that is objectives, non-discriminatory, inclusive and positive (focus on skills and strengths, not behaviour, quality of their work or level of development)

- In collaboration with parents, family and the child involved

- Link to the curriculum for the child in line with the approved learning framework.

A behaviour support plan explains the actions needed to help a child use positive behaviours. It includes long and short-term goals and techniques that educators can use, providing clear explanations of the triggers and the functions of a child’s behaviour. It can also provide acceptable alternative behaviours that encourage the child not to resort to challenging ones. The key is to outline techniques that can be consistently applied to help the child develop skills to communicate their needs appropriately.

Steps for Developing a Behavior Guidance Plan

By outlining systematic steps for assessment, goal-setting, and implementation, educators can ensure that the plan meets the diverse needs of all children. Engaging stakeholders and incorporating feedback are vital components of the process, fostering a collaborative approach to behavior management. This comprehensive guide not only supports the social and emotional development of children but also enhances the overall educational experience, creating a safe and nurturing space for learning.

- Assessment and Data Collection

- Gather information on current behaviors, including observing children in different settings.

- Collect input from educators, parents, and other stakeholders to understand diverse perspectives.

- Identify Goals and Objectives

- Define clear, measurable goals for behavior guidance based on assessment data.

- Establish objectives that align with promoting positive behavior and social skills.

- Develop the Policy Framework

- Create a framework that outlines behavioral expectations, guidelines, and procedures for addressing behaviors.

- Include specific strategies for prevention, intervention, and follow-up.

- Select Observational Tools

- Choose appropriate tools for monitoring behaviors, such as checklists, rating scales, or anecdotal records.

- Ensure tools are easy for educators to use consistently.

- Design Pedagogical Practices

- Outline teaching strategies that promote positive behavior, including modeling, reinforcement, and conflict resolution.

- Incorporate practices that foster an inclusive and supportive environment.

- Engage Stakeholders

- Involve educators, parents, and the community in the development process to ensure buy-in and support.

- Conduct training sessions for staff to familiarise them with the plan and its implementation.

- Implement the Plan

- Put the behavior guidance plan into action in the learning environment.

- Monitor the implementation process, ensuring that all educators are following the established guidelines.

- Continuous Monitoring and Evaluation

- Regularly observe and assess children's behaviors using the selected observational tools.

- Collect feedback from educators and parents regarding the effectiveness of the plan.

- Adjust the Plan as Needed

- Analyse data and feedback to identify areas for improvement.

- Make necessary adjustments to the strategies or framework to enhance effectiveness.

- Ongoing Professional Development

- Provide continuous training and support for educators to keep them updated on best practices in behavior guidance.

- Encourage reflection and sharing of experiences among staff to promote growth and learning.

Consultation with Families and Children

When developing a support plan, the service will involve families and the child in the development process. Collaborating with others is the basis for building a cooperative relationship. The National Quality Standards (NQS), Quality Area 6 – Collaborative partnerships with families and communities, aims to foster and build collaborative and positive partnerships with families and local communities around service.

Research shows that when family, children, other stakeholders and care services work together, benefits to children are lifelong, helping them reach their full potential by influencing and shaping their sense of self and well-being.

The NQS6 places significance on the role of parents and families and that it is respected and supported. In particular, it emphasises that families and care services should work together to create positive environments for children—where they live and learn.

Establishing secure and respectful relationships takes commitment, mutual respect, and cooperation. Respectful relationships create safety and help children build a healthy sense of identity and self-worth. Collaborative relationships are based on interactions that promote one another's ideas, maintaining open communication and mutual respect. Effective communication is the first important step to establishing these relationships. If parents feel well-informed, it will foster a sense of belonging and agency for their children within the service.

Discussing inappropriate behaviours can be emotional, loaded or trigger a negative response in families. They may feel judged, inadequate or have failed if their child is not meeting behavioural expectations. Therefore, educators need to respond appropriately to their needs and reactions. An approach that regards the family as the expert in the child’s care can relieve some tension. Consider:

- Including the family in planning strategies

- Asking about what works at home

- Showing what can be done at home

- Providing information openly, in a non-judgmental manner

- Asking how the family would like to meet (formally or informally)

- Offering information to clarify concerns.

Collaboration also needs to occur with the child. Include them in developing the support plan. You can tailor the child's involvement, so it is appropriate to their needs and age, level of development or developmental stage.

Practice

Child Name: Mia

Age: 5 years old

Mia is a bright and imaginative child who loves storytelling and playing with her friends. However, she has difficulty regulating her emotions, especially when faced with disappointment or frustration.

During a group activity, the teacher asks the children to work together to build a tower using blocks. Mia is excited but quickly becomes upset when her friends decide to use different colors of blocks than she wanted. Feeling left out and frustrated, she starts to cry loudly, expressing her feelings of being ignored. When her friends try to reassure her, Mia struggles to calm down, pushing the blocks off the table in anger. This outburst disrupts the class and causes her peers to become concerned and withdrawn.

- Using the information you have learnt from this module create and design your own inclusion/behaviour plan for each child. You can access an example plan at the following links:

- Behaviour Support Plan Template from the Department of Education and Training (Vic)

- Behaviour Management Plan from the Aussie Childcare Network

- Create review points with specific, measurable, achievable, realistic goals with a specific timeline (e.g. one month, three months, six months [long term or short term]) – be realistic when deciding the timeline. The points should cover the program, pedagogy, values, impact on inclusion or behaviour needs, the learning environment, resources, goals and strategies, collaboration, and professional and specific expertise or knowledge or learning area needs (for the educator).