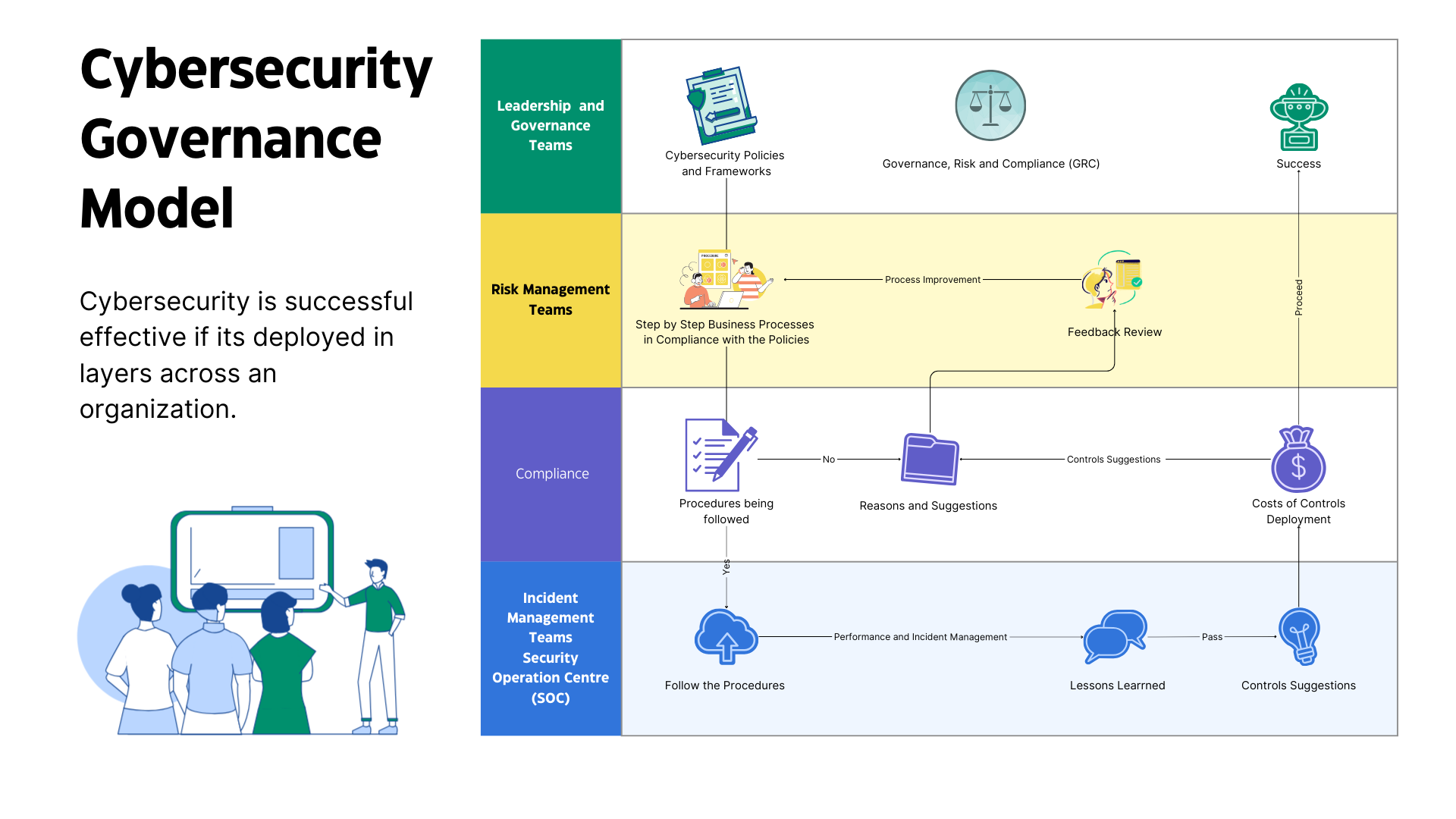

Cybersecurity Deployment and Management works top to bottom. A cybersecurity leader is responsible for creating a vision and setting goals for a team to secure an organization's assets. Additionally, they must understand the technical and legal aspects of the industry and be able to advise on the best approaches for providing appropriate levels of protection. Leaders must have a deep understanding of the industry and its nuances and the ability to make decisions quickly and confidently. A leader in cybersecurity must also possess strong interpersonal skills to communicate effectively with a wide range of technical and non-technical stakeholders. This topic discusses and details the leadership concepts and terminologies in Cyber Security.

The Role of Governance

It is easy for technologists to overlook the impact and importance of effective leadership. While technology is at the heart of a security program, selecting appropriate technologies designed to address carefully analyzed problems is critically important. Looking for quick fixes is understandable, considering the potential impact of cybersecurity incidents. The reality is that when technology projects are driven by emotion, poorly planned, poorly designed, and implemented in a rush, they do little to improve the organization's security posture in a meaningful way. It does not take much research to identify that data breaches continue to increase rapidly but that spending on cybersecurity products is also growing in parallel. One very reasonable conclusion to this disunion is that technology alone is ineffective. Spending money on technology alone does very little. Only when technology is properly managed are its actual impacts realized. Regardless of the technology brand or its features, proper planning and management are necessary to succeed!

The desire for successful technology implementation outcomes drives the need for a program designed to provide critical risk information to leadership teams. In turn, leadership teams are responsible for crafting effective responses by changing policies and processes to reflect their objectives. Establishing governance, risk, and compliance (GRC) teams is a common strategy used to accomplish this goal. Governance teams drive the company's direction and respond to risks. Decisions made by governance teams are grounded in the information provided by risk managers. Risk managers look to compliance teams to help identify if observed business practices align with established rules.

Ultimately, governance teams are responsible for creating and maintaining organizational policies used to direct the work of technical teams. Governance defines the organization's expectations of its employees and its approach to cybersecurity.

The Importance of Policy

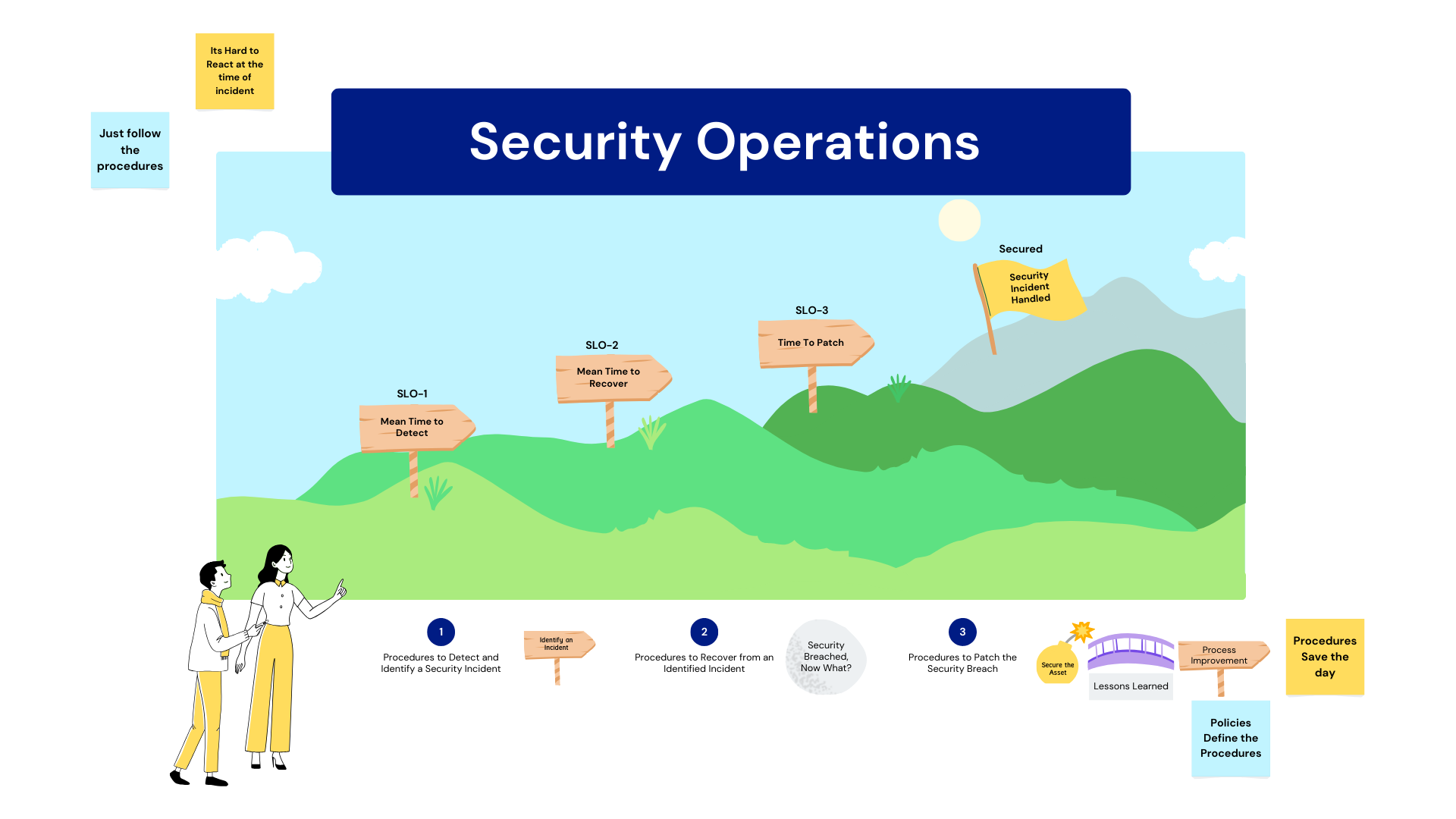

With this in mind, policy and procedure documents become "roadmaps." When properly constructed, policy and procedure documents provide guidance and clear direction. Clear guidance and rules are critically important in cyber operations where one decision or omission can differentiate between effective incident response or disaster. Security operations centers (SOC) depend upon well-established, incident-handling practices and clearly defined responses. It is easy to make mistakes when working under pressure. Well-crafted policies and procedures define response actions and often remove much of the judgment needed when making decisions under pressure. Additionally, policies and procedures steer employees' work to ensure consistent and reliable performance.

Cybersecurity service-level objectives (SLOs) are the standards that organizations and their leadership must meet to ensure the security of their network. These objectives help measure and assess how well security operations protect the organization's assets and assure its customers and stakeholders that systems and data are safe and secure. These objectives must be realistic and achievable, and the organization often reflects the latest security trends and best practices. Some common security-related SLOs include mean time to detect (MTTD), mean time to recover (MTTR), and time to patch.

Compliance teams depend upon policy documents and SLOs to measure work performance and conformance. Actionable statements can be extracted from policies and used to determine if work is being performed in a compliant manner. Furthermore, when risk managers identify new risks, the expectation is that governance teams will codify responses designed to address them by updating policy. This entire process is dependent upon the written rules established in policy documents!

For example, compliance teams may review patch management activities and report back to risk managers regarding the time between the issuance of a security patch and the time taken to apply it. Risk managers use this data to create a trend report that identifies that "time to patch" has increased steadily over the last several months. In response to this new risk item, risk managers work to determine that several change requests related to security patching had their implementation dates pushed back by department leaders. This information is provided to the governance team, who are responsible for crafting a response. The governance team's response might be to establish that any requests to delay security patching require two levels of management approval. The governance team would then codify this decision in the existing change management policy, enabling enforcement.

Risk Management Principles

A risk management program works to identify risks and determine how to minimize their likelihood or impact. After identifying risks, the next step is to handle them using different responses. Responses to risk fall into four distinct categories.

Mitigate

Risk mitigation describes reducing exposure to risk items by implementing mitigating controls to ensure that technical business operations are safe. For example, there are many potential security issues associated with web applications. Since web applications are a critical component of many business processes, we must determine how to operate them safely while meeting the organization's needs. To do this, we use various means to improve the web application's safety and security through mitigating controls.

Avoid

Risk avoidance often means that you stop doing an activity that is risk-bearing. For instance, risk managers may discover that a software application has numerous high-severity security vulnerabilities. After reporting this new finding and providing context to the risks, the governance team may decide that the cost of maintaining the application, or the probability of catastrophic failure due to the newly discovered vulnerabilities, is not worth its benefit and so choose to have it decommissioned.

Accept

Risk acceptance means continuing to operate without change after evaluating an identified risk item. The risk item could be related to software, hardware, or existing processes. It is important to consider that there is risk in all we do; even simple tasks in day-to-day life involve risks. But despite this, we are still productive and largely safe so long as we are aware of risks and act within safe limits. Helping organizations operate in this way is precisely the goal of risk management—to help contain risks within carefully constructed and mutually agreed-upon boundaries because it is impossible to eliminate risk.

By implementing effective mitigating controls, we can reduce the overall risk. We implement mitigating controls until risk levels are reduced to a level deemed "acceptable" by risk managers and governance teams.

Transfer

Risk transference (or sharing) means assigning risk to a third party, which is most typically accomplished through insurance policies. Insurance transfers financial risks to a third party. This is an important strategy as the cost of data breaches, and other cybersecurity events, can be extremely high and result in bankruptcy.

Watch the Video in Comptia CySA Student Guide.

Watch the Video in Comptia CySA Student Guide.

Risk Management Exceptions

Despite the presence of mitigating controls, some risks may still be troublesome. It could also be that mitigating controls are not available to help reduce the risk level. For example, a different risk response might be warranted, like avoidance. Circumstances may warrant a risk exception if a different risk response is not reasonable or feasible. Issuing a risk exception is a serious decision and must include careful documentation identifying why the risks are concerning and specific justifications describing why an exception is warranted. The explanation should document the dates when the decision to issue an exception was made and include the signatures of all involved.

Threat Modelling

When considering appropriate risk responses, it is essential to understand precisely which threat actors are in scope for the organization. The most advanced adversaries typically focus on military, federal-level government agencies, high-tech companies, and large financial institutions. Accurately identifying threat actors that may turn their attention to the organization helps shape appropriate response and detection capabilities. Many organizations need only foundational levels of cyber capability because the resources required to resist an advanced adversary typically outstrip the resources available to most organizations.

Threat modelling is designed to identify the principal risks and tactics, techniques and procedures (TTPs) that a system may be subject to by evaluating the system both from an attacker's point of view and from the defender's point of view. For each scenario-based threat situation, the model asks whether defensive systems are sufficient to repel an attack perpetrated by an adversary with a given level of capability. Threat modelling can be used to assess risks against corporate networks and business systems, and it can also be performed against more specific targets, such as a website or software deployment. The outputs from threat modelling can be used to build use cases for security monitoring and detection systems. Threat modelling is typically a collaborative process, with inputs from a variety of stakeholders. In addition to cybersecurity experts with knowledge of the relevant threat intelligence and research, stakeholders can include nonexperts, such as users and customers, and persons with different priorities to the technical side, such as those who represent financial, marketing, and legal concerns.

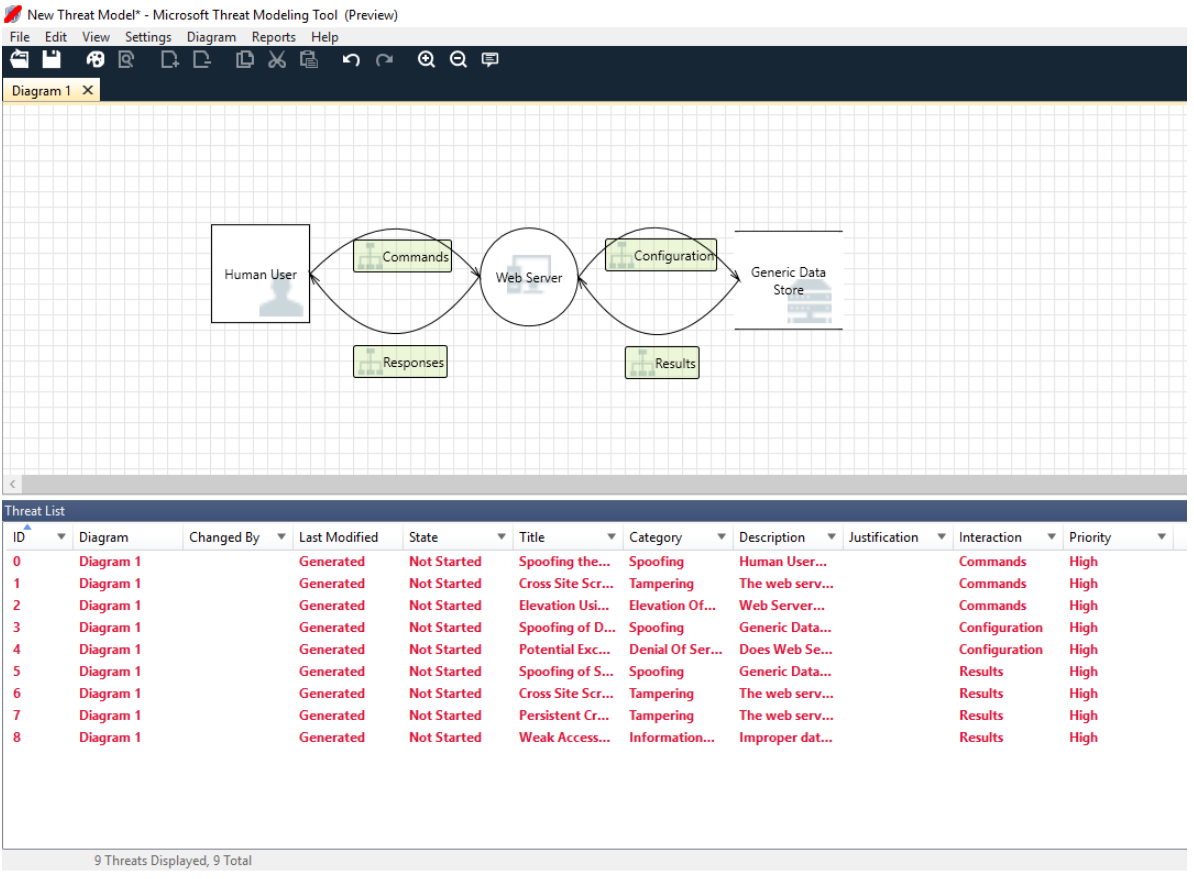

This is the Threat Model diagram using Microsoft Threat Modelling Tool. The window has two sections: a Diagram section at the top and a Threat list below.

The first section has a tab that reads "Diagram 1". A square labelled Human User, a circle labelled Web Server, and a square labelled Generic Data Store are depicted from left to right. A curved arrow labelled Commands points from Human User to the Web Server, and a curved arrow labelled Responses points back to Human User. A curved arrow labelled Configuration points from the Web Server to the Generic Data Store, and a curved arrow labelled Results points back to the Web Server.

The second section has a header that reads "Threat List." Below this is a table that consists of 11 columns and 9 rows. The columns represent different aspects of each threat, including I D, Diagram, Changed By, Last Modified, State, Title, Category, Description, Justification, Interaction, and Priority. Some categories include Spoofing and Tampering. The threats are sorted by Interactions, which include Commands, Configuration, and Results.