What is a Treaty?

Throughout our lives we make many agreements with others. They can be informal and unwritten (e.g. being friends with someone, going out on date, arranging to meet somewhere for coffee) or they can be more formal and often written (e.g. signing a rental agreement, getting hire purchase, buying a house). What these agreements do is outline the responsibilities and obligations of the relationship between you and the other person or party. You could also call these agreements a contract, compact or even a treaty.

The term ‘treaty’, however, is usually reserved for the agreements that are made between countries or groups of people (e.g. tribes, ethnic groups). Encyclopedia Britannica defines treaty as1:

a binding formal agreement, contract, or other written instrument that establishes obligations between two or more subjects of international law (primarily states and international organizations).

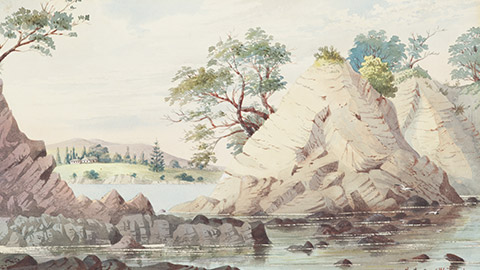

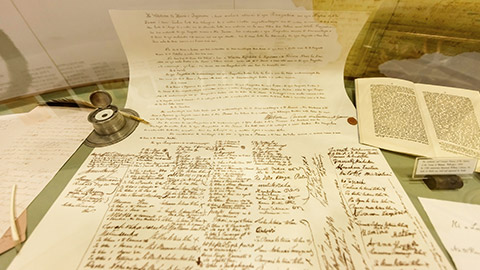

On 6 February 1840, the Treaty of Waitangi/Te Tiriti o Waitangi was signed at Waitangi in the Bay of Islands by Captain William Hobson, several English residents, and between 43 and 46 Māori rangatira.

Task: Reflect on prior knowledge

Before continuing to read and learn about Te Tiriti o Waitangi reflect on these questions:

- What do I know currently about Te Tiriti o Waitangi/The Treaty of Waitangi?

- Where did I learn this knowledge?

- Why is Te Tiriti o Waitangi/Treaty of Waitangi important for Aotearoa New Zealand? And in particular, why is it important for youth development work?

If you have already learned about the articles of Te Tiriti and the circumstances surrounding the signing of the different documents – either in school or in a different course – then you may find that you already know most of what is covered in the first half of this topic.

The Story of Te Tiriti

Te Tiriti o Waitangi/The Treaty of Waitangi is an agreement signed by the sovereign independent Māori tribes (iwi) and the representatives of the British Crown. It is considered as one of the founding documents of Aotearoa, and set out the obligations and responsibilities of how Māori and the Crown (on behalf of the British settlers) would live together peacefully in Aotearoa.

At the time of the signing of the treaty, the Māori population was around 100,000; the number of settlers was only 2,000.

There has been much written about how Te Tiriti o Waitangi was written, how it was signed, and the subsequent ‘journey’ of the treaty around Aotearoa.

Te Ara: The Encyclopedia of New Zealand provides a good overview of the story of the Treaty of Waitangi – click on the link and read the story.2

For further information you can read and watch some other resources online at the website of Te Papa Tongarewa Museum of New Zealand.3

From the sources you have just looked at, we know the following facts:

- Te Tiriti o Waitangi was signed on 6 February 1840.

- William Hobson was the Crown representative.

- The missionary Henry Williams and his son Edward translated the English draft into Māori.

- More than 40 Māori chiefs signed Te Tiriti/the Treaty at Waitangi.

- Two versions of the Treaty existed – English and Māori.

- The textual differences between the two documents have been a source of much debate and disagreement.

- Breaches of Te Tiriti have led to conflict, and the oppression of Iwi Māori.

The founding document of a nation

In the readings you will have come across the fact that while many people regard Te Tiriti o Waitangi/Treaty of Waitangi as a founding document of our nation, it has also been the source of much debate, conflict and contention.

Task: Contentious issues

Before continuing, take a few moments to think about, and jot down (if you wish), the issues or challenges that might be raised in any discussion about Te Tiriti o Waitangi. Here are some examples for you:

- “The Treaty is a historical document and has no relevance in the 21st century.”

- “We are all New Zealanders, so why do we need it?”

- “Iwi Māori have experienced numerous breaches of te Tiriti.”

Two Versions of the Treaty/Te Tiriti

The missionary Henry Williams supported the British annexation of Aotearoa New Zealand because he believed that Māori should be protected from the lawless behaviour of the English settlers, and their fraudulent dealings in commerce (e.g. land purchases and speculation).

Along with his son, Edward, he translated the English draft of the Treaty into Te Reo Māori. This led to several important differences in the text of Te Tiriti o Waitangi. Two versions of the Treaty/Te Tiriti exist. These textual differences have been the source of much debate and conflict.

Both the Māori and English versions of Te Tiriti o Waitangi made promises to Māori. The promises in the Māori version generally provided stronger rights for Māori than those in the English version.

Click here to read the text of the two versions (including a translation in English of what the Māori version says) on the Te Papa website.4

Here is a summary of the articles of Te Tiriti in the Māori and English versions:

|

|

Māori Version | English Version |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | This article gave Queen Victoria governance (kawanatanga) over the land. The word ‘kawanatanga’ came from the transliteration of the English word ‘governor’. Before Te Tiriti, ‘kawana’ had been used in te reo Māori to refer to the governor of New South Wales (who was under the Queen) and to Pontius Pilate in the Bible (who was under Caesar). People at the time would not have understood it as meaning sovereignty or having complete power over New Zealand. |

This article gave Queen Victoria sovereignty over New Zealand. This was a much stronger right than kawanatanga or governance, which many Māori interpreted as setting up a government to control the Pākehā settlers. |

| 2 |

This article stated that the chiefs would retain their full chieftainship rights (te tino rangatiratanga) over their lands, villages, and all other treasures. |

This article guaranteed the chiefs full, exclusive, and undisturbed possession over their lands, estates, forests, fisheries and all other properties. This was not as strong as having “full chieftainship rights” and was limited to property, whereas treasure had a wider meaning. |

| 3 |

This article guaranteed Māori the same rights as British citizens. |

Article 3 is considered to have a very similar meaning in English. |

| 4 |

Article 4 was a discussion between the Catholic Bishop Pompallier and the Anglican missionary William Colenso in relation to religious freedom in New Zealand. William Hobson, the governor, agreed to protect “several faiths (beliefs) of England, of the Wesleyans, of Rome and also of Māori custom (Tikanga Māori)”. This article guaranteed religious freedom for all in the new nation, including Māori. |

As this article was an oral discussion, the English version of the Treaty did not include it. |

The differences between the two treatys can be outlined in the following way:

- Article 1: Kawanatanga (Governership) VS. Sovereignty

- Article 2: Tino Rangatiratanga VS. Exclusive, undisturbed possession

- Article 3: Both grant the rights of British citizens

Which version of the Treaty is the correct one?

Because differences exist between the Māori and English versions of the Treaty disagreement has arisen. A legal principle – contra proferentum – holds that where two versions of a legal document exist, the version which favours the party that didn’t write the document should be followed. This means that in the case of Te Tiriti o Waitangi the version written in Te Reo Māori should be the one that is followed.

Breaches of Te Tiriti

The history of colonisation in Aotearoa New Zealand is littered with examples of breaches of Te Tiriti. Up until the 1970s, parliament and the courts generally ignored Te Tiriti. The Waitangi Tribunal was established in 1975, acting as a commission of inquiry into Treaty breaches and grievances. The Tribunal is responsible for researching breaches of Te Tiriti by the Crown (the New Zealand government) and its agents, and making recommendations for redress of the grievances. In most cases, the recommendation of the Waitangi Tribunal are non-binding, but in many instances the Crown has accepted that it breached the Treaty and its principles.

The formation of the Waitangi Tribunal led to discussions with the government and the courts that sought to ‘thrash out’ the principles of Te Tiriti o Waitangi. As summarised in Te Ara: “The treaty is deemed to bind Māori and Pākehā New Zealanders in a partnership in which they must act reasonably and with utmost good faith”, and the principles are one way in which this is articulated.5

The first time these principles were used was in the Act of Parliament that formed the Waitangi Tribunal. Since that time there have been other official references to treaty principles. Because these principles have been defined through court cases, new laws, Waitangi Tribunal findings and a 1989 government statement, there is no final or complete list of Treaty principles.

However, it is agreed that these principles are included:

The Treaty set up a partnership, and the partners have a duty to act reasonably and in good faith.

- The Crown has freedom to govern.

- The Crown has a duty to actively protect Māori interests.

- The Crown has a duty to remedy past breaches.

- Māori retain rangatiratanga over their resources and taonga and have all the rights and privileges of citizenship.

- The Crown has a duty to consult with Māori.

- The needs of both Māori and the wider community must be met, which will require compromise.

- The Crown cannot avoid its obligations under the Treaty by giving authority to some other agency.

- The Treaty can be adapted to meet new circumstances.

- Tino rangatiratanga includes the management of resources and other taonga according to Māori culture.

- Taonga include all valued resources and intangible cultural assets.

For many years, and even nowadays, many social services and health organisations (including government agents) have used the ‘3Ps’ framework to incorporate treaty-based ideas and practice into the work they do.

This well-established Crown Treaty framework came out of the 1986 Royal Commission on Social Policy. The three principles are Partnership, Participation and Protection. Does this sound familiar to you?

These principles, though widely used, are now regarded as outdated, and it is accepted that they are a ‘reductionist view’ of Te Tiriti.6

The fourth Labour government became the first government to set out a set of principles to guide it on matters relating to Te Tiriti in 1989. No later government has defined any new principles since.

The principles are:

- The Kawanatanga Principle: The government has a right to govern and make laws

- The Rangatiratanga Principle: Iwi have the right to organize as iwi, and under the law, to control their own resources.

- The Principle of Equality: All New Zealanders are equal before the law

- The Principle of Reasonable Cooperation: Both the government and iwi are obliged to accord each other reasonable cooperation on major issues of common concern

- The Principle of Redress: The government is responsible for providing effective processes for the resolution of grievances in the expectation that reconciliation can occur.

The 2019 Waitangi Tribunal Report ‘Hauora: Report on Stage One of the Health Services and Outcomes Kaupapa Inquiry’ has recommended a set of principles to provide a new framework for how government health & disability organisations (and consequently non-governmental organizations) can meet their obligations under Te Tiriti, not only in planning but in their day-to-day operations. These principles are also being adopted in the social services, including youth work.

The principles applicable to health and disability services are as follows7:

The guarantee of tino rangatiranga provides for Māori self-determination and mana motuhake in the design, delivery, and monitoring of services.

The principle of equity requires the Crown to commit to achieving equitable outcomes for Māori.

The principle of active protection, which requires the Crown to act, to the fullest extent practicable, to achieve equitable outcomes for Māori. This includes ensuring that it, its agents, and its Treaty partner are well informed on the extent, and nature, of both Māori outcomes and efforts to achieve equity for Māori.

The principle of partnership, which requires the Crown and Māori to work in partnership in the governance, design, delivery, and monitoring of services. Māori must be co-designers, with the Crown, of systems for Māori.

The principle of options, which requires the Crown to provide for and properly resource kaupapa Māori services. Furthermore, the Crown is obliged to ensure that all services are provided in a culturally appropriate way that recognises and supports the expression of Māori models of care and practice.

Task: Reflect on applying Treaty principles to youth development

As you prepare to complete the first assessment task, think about the Treaty principles you have been introduced to and consider how they might be applied to youth development. What do you think youth development services and practice might look like?

You will revisit the application of these principles in youth development in later topics as well.

The Treaty Principles and Youth Development

You have already been introduced to the Youth Development Strategy Aotearoa in a previous topic. One of the principles of that strategy states “youth development is shaped by the ‘big picture’”. Te Tiriti o Waitangi is an aspect of the ‘big picture’.

The Treaty principles you have been introduced to provide a framework for the provision of culturally aware, sensitive, and safe services and practices when working not only with rangatahi Māori, but with youth in general. Each of the principles are discussed below with a consideration of their application in youth development.8

Principle 1: Recognition and protection of tino rangatiratanga

This is guaranteed under Article 2 of Te Tiriti. It means that the right of Māori to organise in whatever way they choose – whānau, hapū, iwi or other form of organisation – and to exercise autonomy and self-determination to the greatest extent must be recognised and protected.

An example of this principle in action is the way in which iwi are able to manage any treaty settlement compensations in the way they see as appropriate to support the iwi. Kai Tahu purchased a controlling share in Sealord, and Tainui have invested successfully in commercial property developments.

Principle 2: Equity

This is an Article 3 Treaty commitment. It is also about acting in good faith as a Treaty partner.

Equity is not just about allowing equal access to services for all. The Waitangi Tribunal highlighted that equity is also not just about reducing disparities. It involves the bigger goal of equitable outcomes for Māori.6

The Tribunal approved the World Health Organisation’s definition “Equity is the absence of avoidable or remediable differences among groups of people, whether those groups are defined socially, economically, demographically or geographically.”9

Sometimes to achieve equity there is an unequal distribution of resources in favour of the group that experiences the greater disparity. For example, where youth services are funded there will be more funding given to services that work with Māori youth, or areas with a high population of young Māori.

Principle 3: Active protection

This principle is all about action and leadership. Devolution and permissive arrangements without Treaty leadership are not sufficient. Provision for equal opportunity or a “one-size fits all” approach also falls short.

The Crown must actively pursue and do whatever is reasonable and necessary to ensure the right to tino rangatiratanga and to achieve equitable health and social outcomes for Māori.

Protection is about ensuring rangatahi have access to services that meet their needs. This also means the services are culturally appropriate and sensitive to meeting the needs of each person – cultural, emotional, physical and spiritual. Service providers should protect the dignity and mana of rangatahi, which requires:

- advocacy

- protecting the things that are important to rangatahi

- knowledge and awareness

Protection relates to Article 3 of Te Tiriti o Waitangi.

Principle 4: Partnership

Yes, this “P” remains. Its meaning reflects an interplay of Articles 1 and 2 of Te Tiriti o Waitangi.

For the Crown to be a good governor it must recognise and respect the status and authority of Māori to be self-determining in relation to resources, people, language and culture (i.e. tino rangatiratanga). It must involve Māori at all levels of decision making.

Both the Treaty parties must act reasonably and in good faith towards each other.

In youth development, partnership is about working together with young people, their family/whānau, iwi and hapῡ. This means that they are all involved in the person’s support.

For a real partnership, it means valuing the young person and their support networks, having empathy and sharing decision making and resources. It is about sharing skills and treating people in the relationship with equality. Working in partnership requires everyone to:

- respect and value differences.

- show empathy.

- share knowledge and empower others.

- share decision-making processes.

Principle 5: Options

This principle is about giving real and practical effect to the principles of tino rangatiratanga and equity; Articles 2 and 3 of Te Tiriti. Where kaupapa Māori services exist, Maori should have the option of accessing them as well as culturally appropriate mainstream services. They should not be disadvantaged by their choice.

It is the job of the Crown to ensure each option is viable and sustainable by providing sufficient financial and logistical support, strong leadership and effective monitoring.

Relevance of Treaty principles to youth work

There are many ways in which these principles can be applied in youth work practice. Organisations, as well as individuals, must all play a part in ensuring Te Tiriti o Waitangi is integral to practice.

Here are some examples of areas in which the principles can be applied within an organisation that works with young people.

Organisational Level:

- planning

- policy

- service provision

- staffing

Individual Level:

- relationships with tangata whenua

- relationships with tauiwi (non-Māori)

- service delivery

As you move into completing your assessment, have a think about the areas in which Treaty principles can be applied, and consider what types of activities or actions could be taken in each area to ensure your practice becomes Tiriti-compliant.

In this topic and in future topics you will encounter a number of kupu Māori (Māori words/terms). You may know some of these already, but if you come across kupu you are unfamiliar with, you can use this online Māori–English Dictionary.10

Read the assessment question and think about what you would like to focus on. Do you think you have enough information to complete the task? If not, what else do you need, and do you know how to find or access that information?

You are now ready to complete Task 1 of Assessment 1.4.