Who are Pasifika peoples?

Pacific or Pasifika people are made up of many Pacific Island nations such as Samoa, Tonga, Cook Islands, Niue, Fiji, Tokelau, Tuvalu, Kiribati and many more.

There is no one single Pasifika or Pacific Island identity, as the term Pasifika represents a diverse range of Island nations under three sub-regions – Polynesia, Melanesia and Micronesia. There are different Pasifika languages, cultures and customs.

Pasifika people can also be known as Pacific peoples, Pasefika, Tagata o le Moana, Tagata Pasifika, Oceania, or Tangata o te Moana Nui a Kiwa. Others would say they are proud Polynesians (the term Polynesia only represents the Pacific nations that are in that sub-region).

The terms ‘Pacifika’ or ‘Pacifica’ (note the spelling) are not commonly used amongst Pasifika to identify themselves. Instead, Pasifika is used.

In New Zealand, the Pacific population is growing and it is a young population – with a median age of 23 years old (according to 2018 Census data).1 The majority of Pacific youth were born here. The culture of NZ-born Pacific people may be expressed differently here than it is in the islands.

Task: Reflect on historical impact

Different Pacific cultures may have different relationships with New Zealand. Think about historical, social and political factors such as colonisation, early migration in the 60s and 70s, the dawn raids, and more recent history. Reflect on how this could influence Pacific youths’ identity – their sense of themselves and their culture.

What values do Pasifika peoples have in common?

There are some values that are found across Pacific cultures, which we will call common values, though they may have subtle differences between cultures. While these values are not unique to Pacific cultures, they influence everyday life and how people interact with each other in any situation.

These common values include:

Respect is observed in many different ways. Respect of relationships is important, and this includes respecting elders. Youth may act differently when they are with their family or in front of elders, as a way of showing respect.

Reciprocity is the two-way process of giving, receiving then giving in return. It is not the same as a trade or exchange as it’s not about getting the best deal for yourself. Reciprocity also applies to trust and loyalty in relationships. Everyone works together, giving and achieving.

Relationships with family, community, church and village are valued. Because of this, it’s important to consider the opinions of others. Pacific youth may need to find a balance between emphasising individual relationships and communal relationships.

Most Pacific people identify with at least one religion.

This is a holistic view of the person, seeing them as not just their physical and mental self, but also including their family, culture, environment and spiritual life. This means a Pasifika youth might think about themselves as not just an individual but as part of their family, home, community, history and culture and relationships.

Explore further

This article 'Reciprocity: What is it and what are its implications?' by Kaitu'u 'i Pangai Funaki gives a concise overview (from Dr Funaki's Tongan perspective) of the role of reciprocity and its importance in forming relationships in Pacific cultures.2

Read the article and think about whether you could incorporate reciprocity in any aspects of your work.

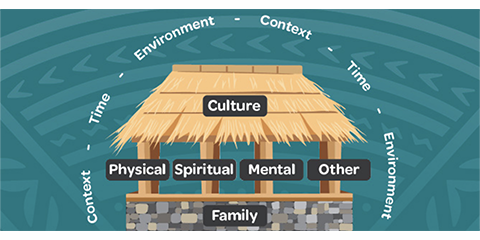

There are a variety of frameworks and models that can be used to understand Pacific cultural values. The Fonofale model (developed by Fuimaono Karl Pulotu-Endemann) is one model that shows a holistic view of health and well-being, where many values are interrelated.3

Dimensions of the Fonofale model

What makes the Fonofale model different from other models of health and well-being is that it incorporates Pasifika values and perspectives.

The foundation or floor of the fale represents aiga, or family, which is the foundation of Pacific Island cultures. This includes not only your blood relatives, but extended family and anyone you are connected to by partnership or other agreement.

The roof represents your cultural values and beliefs, which is the shelter that protects the family. This can refer to traditional cultural values and practices, but because culture is dynamic, in the New Zealand context this also includes the culture of Pasifika peoples who were born and raised here. This can also apply to families and households that focus more on Palagi identity and values.

There are four main pou, or pillars, between the foundation and the roof. These pou all connect the family and culture but they also interact with each other.

- Your spiritual well-being, which can relate to your sense of well-being associated with your religious faith, traditional spiritualiy, or a combination of both

- Your physical well-being, which includes your biological health and physical fitness

- Your mental health and well-being, which encompasses your thoughts and emotions as well as the behaviours you express

- Other aspects of your well-being, which can include other variables and aspects of your identity that can have an impact on one’s health, such as gender, sexual orientation, age, socio-economic status

None of these six dimensions of the Fonofale can stand alone – they all depend on the other dimensions for support and strength. The entire Fonofale is further enclosed by three more dimensions that can have direct or indirect influences on an individual or the whole family’s well-being.

- The environment surrounding the fale is the dimension of your physical environment, such as the area where you live and work, or whether you are in a rural or urban setting.

- Time relates to the specific point in history we are at currently, and how that impacts on Pasifika peoples.

- The surrounding societal context includes things like which country you live in, the legal system, or political factors. This dimension can affect people’s lives in all kinds of direct and indirect ways.

Watch this video explanation by Jonathan 'Ilaua to get another perspective on the Fonofale model.4 (Note that this video is titled ‘TED Talk’ but it is not actually a TED Talk presentation.)

Task: Apply the Fonofale to your own life

Reflect on how the Fonofale model applies to your own life and consider these questions.

- What does your foundation look like? How does the solid base of your family life influence your well-being or success in a typical day or week?

- What does your roof look like? What are the cultural values or belief systems you’ve inherited that help you in your daily life?

- What is it that keeps each of your main pou strong and able to support your roof and foundation? Think about your spiritual, physical and mental health, as well as other aspects of your personal well-being.

Explore further

If you would like to read the full articles yourself, here are the sources for this section.

- Fonofale Model of Health by Fuimaono Karl Pulotu-Endemann3

- The Springboard Trust has an article titled A resilient home: The Fonofale Model of Health, which summarises the main points from Fuimaono Karl’s model5

What is collectivism?

Pacific cultures are more collective than individualistic. In a collective culture:

- people see themselves as part of a group such as a family or community

- people think of themselves in terms of their relationships with others

- the needs of the group are important – people choose to prioritise the common good

- people need others – they are interdependent – and group harmony is important

- there is more collaboration, decisions are made together, and resources are shared

- people are expected to conform to the group; there is a sense of obligation and duty.

When working with Pasifika youth, the space you provide may need to be welcoming to both the individual youth and their family. An Australian resource for culturally competent youth work is Culturally-Competent Youth Work: Good practice guide from the Centre for Multicultural Youth, which is a four-page guide that gives some guidelines for being inclusive of families and communities.6

This well-known quote by Tui Atua Tupua Tamasese Taisi Efi encapsulates this sense of collectivism7:

I am not an individual; I am an integral part of the cosmos. I share divinity with my ancestors, the land, the seas and the skies. I am not an individual, because I share a tofi (inheritance) with my family, my village and my nation. I belong to my family and my family belongs to me. I belong to my village and my village belongs to me. I belong to my nation and my nation belongs to me. This is the essence of my sense of belonging.Tui Atua Tupua Tamasese Taisi Efi

For those who work with young people, it is important to be aware that Pasifika people in Aotearoa New Zealand (and in other countries) often see themselves as one part of a collective world view. Adapting elements of how you engage with, teach and learn from these young people can improve your practice.

In her article Talanoa with Pasifika youth and their families, Julia Ioane explains8:

[Pasifika youth] are generally taught to respect their elders and those in authority, with an expectation to prioritise the needs of the community over their own individual need. An initial reluctance by Pasifika youth to engage can be interpreted incorrectly as non-compliance. However culturally, Pasifika youth can be reluctant to genuinely engage unless appropriate processes that include acknowledgement of their families and elders is prioritised. This is generally due to Pasifika youth showing their respect and maintaining the va towards their parent or elder. Expectedly, this can be a challenge for many non-Pasifika practitioners/clinicians as this can place constraints on resource and timing. However, once a genuine relationship is established, participation and maintaining engagement will be less challenging. At this point, it is important to comprehensively explore the role of the young person within their family, among friends and in social settings that may include the church.Julia Ioane

Task: Extended family

What do you do to be inclusive and/or welcoming of the extended family of the young people you work with?

What is Vā?

Vā is a Samoan term that literally means ‘space’; this is the space or relationship that connects people, church and the environment. (It is pronounced ‘Vaaah’.) An important aspect of vā is nurturing and maintaining the relationships between people and things you are connected to. Vā involves negotiating space to maintain harmony, reciprocity and mutual respect.

A common saying in Samoan is Teu le vā – this means to care for the vā, to nurture the relationship.

Vā recognises how the dimensions of culture, family, spirit, physical, mental and environment are inter-related, and how our relationships influence these.

Task: Pasifika insight in the Code of Ethics

The space of boundaries and confidentiality gives safety in the vā. Read the ‘Pasifika insight’ on page 37 of the Code of ethics for youth work in Aotearoa New Zealand.9

Le Va Pasifika have published a one-page Pasifika youth participation guide based on Pacific values.10 You may wish to download your own copy of this guide, or print it and put it somewhere you can see it when at work. There are nine points leading to full participation; note how point 5 is ‘Nurturing the va’.

Task: Nurturing vā in your own work

Reflect on what you have learned and consider these questions.

- How would you apply the concept of vā to your youth work?

- What might ‘nurturing the vā’ look like in your workplace?

What is Talanoa?

Talanoa is a term used in Fijian, Samoan and Tongan, and it means to have an open conversation or discussion. It is a way to share stories and ideas, build relationships and solve problems.

Tala – to speak, ask, talk, tell stories, inform, command or relate.

Noa – ordinary, of no value, without concealment, without exertion.

Talanoa is not a value, but a process that is used in research, education and decision-making. It is a way of interacting that is flexible, not structured, and allows for knowledge to be shared and created together. It builds relationships and gives an opportunity for more authentic thoughts and ideas to be discussed, by creating the right conditions for that to happen.

Understanding the vā allows the fruition and progress of your talanoa. Telling our story makes connections.

Talanoa might start with chatting with people about their day and what they’ve been doing, sharing your own stories, and building that relationship until you are accepted into the group and they feel comfortable talking with you. Then you can have that open conversation once the relationship is there.

Talanoa can be held in a casual or a formal platform.

For example, a casual talanoa can start by someone asking for your name and village – instantly a conversation and relationship is built from asking those two questions.

As an example of formal talanoa, if you were visiting a youth and their family for a certain purpose (a talanoa on the youth’s progress and also what they need assistance with), you would not talk initially about the youth or why you are there. Instead, you would talanoa first about how the family are, etc. before they ask why you have come to visit.

Other values embodied in talanoa

Talanoa follows the oral traditions of telling stories to share information and it embodies important Pasifika values. Here are examples of how some other values are expressed in talanoa:

- Relationship building: Talanoa builds the relationship before starting the work

- Reciprocity: You share your own thoughts and stories, and share in the work so others will do the same.

- Respect: Building the relationship first breaks down some barriers and the need for formal respectful behaviour towards you as a person in a position of authority or of an age with more power.

- Spirituality: A talanoa process may begin and end with a prayer.

Explore further

Here are two more articles – you may find these optional readings interesting or relevant to your youth work practice.

- This Art Beat article 'Talanoa I Measina – Sharing Our Stories in Tūranga' by Warren Feeney is about an art installation celebrating how Pacific culture is expressed in Ōtautahi Christchurch.11

- The research paper 'Pacific ways of talk – hui and talanoa' by David Robinson and Kayt Robinson is a case study that explores 'Pacific ways' of discussing issues by focusing on and contrasting Māori hui and Fijian talanoa.12

Task: Incorporating talanoa into your work

Reflect on what you have learned and consider these questions.

- How would you apply the concept of talanoa to your youth work?

- What might it look like to try and incorporate talanoa in your workplace?

Values driven approach

A youth development practice that follows Pasifika values may be fluid, while the values remain consistent. The important thing is to value and nurture relationships.

You may need to get creative when thinking of how to create safe spaces when working with youth and adapting inclusive cultural protocols in the kaupapa.

Task: Strategies to effectively support Pasifika learners

Look at the article 'Four strategies to effectively support Pasifika students' by Dr Vicki Hargraves at The Education Hub.13 The article outlines four broad strategies and gives examples of how you could exemplify each strategy in practice.

You do not need to read the whole article at once – rather, pick one of the four strategies and read the description and examples under that section. Think about how you can implement this strategy in some small way in the work you do over the next week.

Then, once you are comfortable you have worked that strategy into your day to day practice, you can revisit this article another week and pick one of the other strategies. Repeat this process until you have read about and embedded all four strategies into your youth work practice.

Are you confident you have a good understanding of the Pasifika values we have covered in this topic?

- Do you recognise some values that are important to Pasifika youth?

- Do you have some ideas for an activity that incorporates these values in your work?

You are now ready to complete Task 2 of Assessment 1.5.