The Treaty of Waitangi - Te Tiriti o Waitangi - is the founding document of New Zealand. It is an agreement entered into by representatives of the Crown and Māori iwi (tribes) and hapū (sub-tribes).

The treaty was created because of the needs arising from settlement, land transactions and unruly behaviour of new arrivals; but was hurried along because of French interest in New Zealand.

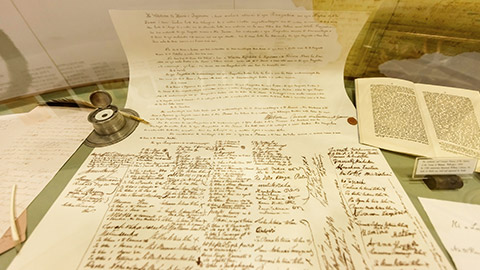

The Treaty was prepared in just a few days. Missionary Henry Williams and his son, Edward, translated the English draft into te reo Māori overnight on 4 February 1840.

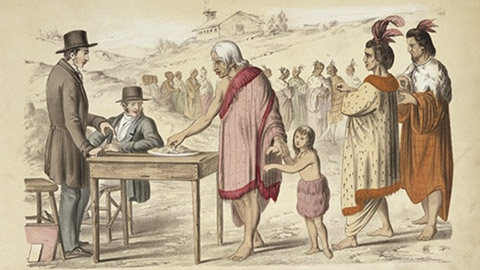

About 500 Māori debated the document for a day and a night before it was signed.

On 6 February 1840, the Treaty of Waitangi/Te Tiriti o Waitangi was signed at Waitangi in the Bay of Islands by Captain William Hobson, several English residents, and between 43 and 46 Māori rangatira.

Why did the British Crown want a Treaty?

The British Government was considering establishing a form of civil government in New Zealand because of the increasing number of British people arriving to live in New Zealand. However, a plan for private settlement by the New Zealand Company forced the British Government to act. The government instructed Captain William Hobson to act for the British Crown in negotiating a treaty because it was necessary to obtain Māori consent before establishing any form of government.

Signings throughout the country

After the signing at Waitangi, the Māori text of the Treaty was taken around Northland to obtain additional Māori signatures. Copies were also sent around the rest of the country for signing. By the end of that year, over 500 Māori had signed the Treaty. Of those 500, 13 were women. The English text was signed only at Waikato Heads and at Manukau by 39 rangatira.

The Treaty in te reo Māori was deemed to convey the meaning of the English version, but there are some significant differences.

In the Māori version, the word ‘sovereignty’ was translated as ‘kawanatanga’ (governance).

- Sovereignty: the power or authority to rule.

- Kāwanatanga: government, dominion, rule, authority, governorship and province. The English version guaranteed ‘undisturbed possession’ of all properties, but the Māori version guaranteed ‘tino rangatiratanga’ (full authority) over ‘taonga’ (treasures, which can be intangible).

- Tino rangatiratanga: chieftainship; full, exclusive and undisturbed possession. Today, the Treaty represents so much more, emphasising equity, education and preservation of Māori culture and Tikanga.

- Tikanga: A Māori concept with a wide range of meanings–culture, custom, ethic, etiquette, fashion, formality, lore, manner, meaning, mechanism, method, protocol and style.

It is common now to refer to the intention, spirit or principles of the Treaty.

While not part of the original document, the simplified principles (often referred to as the '3Ps') have become the go-to reference for helping people understand how to apply the Treaty of Waitangi to their work and daily life.

Partnership

Acknowledges sovereignty/governance and working together with the same rights and benefits as subjects of the Crown. This principle is about equality and equity between Māori and all other New Zealanders. It is working together at all levels of an organisation and having a say in the policy and management of organisations. It means engaging with Māori in the community when you plan work that affects them.

Protection

Acknowledges the protection of rights, benefits and possessions. As well as ensuring equal rights and protecting possessions, it means that Māori tikanga (culture and protocols) and taonga (treasures) such as Te Reo Māori (Māori language) are respected and given equal footing to the tikanga and taonga of other cultures.

Participation

Acknowledges sovereignty and governance. 'Participation' means ensuring equal participation at all levels and that Māori have input into decision-making directly affecting them.

Awareness of cultural appropriation has become more widespread in recent years. As the spread of information and knowledge on the subject increases, the negative impact of the process is more evident than ever.

What is cultural appropriation?

'Appropriation' refers to the act of adopting or using an element or elements of another culture. It is selective and involves the picking and choosing of elements primarily for their aesthetic value without understanding the value they have and their context within the culture they are from.

Culture

Culture can be defined as 'the ideas, customs and social behaviours of a particular people or society'. It is worth noting that culture is not defined along geographical or racial lines. It applies to groups of people.

Elements of culture

When discussing culture in sociological terms, we often refer to the 'element(s) of culture'. These elements help us understand more about the context of cultural elements being appropriated.

Symbols

Symbols can be a form of nonverbal communication. They can be placeholders that are intended to represent something else and to evoke emotion by association.

Religions often have a wide variety of symbols that have specific meanings. For example, the crucifix and the Star of David. Other cultural symbols include the yin and yang symbol.

Symbols do not have to be physical or written. The act of shaking hands in many cultures is a symbol of politeness in greetings. Holding hands can show a loved one (and the people around you) your feelings. Giving a 'thumbs up' is another example of a cultural symbol.

Not all cultural symbols have positive effects on communities. The MAGA hat and the BLM t-shirt are examples of cultural symbols that elicit negative responses for those on the other side of their aligned cultures.

Language

Languages, both written and spoken, are some of the most significant ways culture is shared and passed on. A shared language is essential to the development and evolution of a culture.

Language does not have to mean the dominant language spoken in a particular country (English, Māori, French etc.). It can also refer to the colloquialisms found within a culture; for example, the culture of car enthusiasts has words and phrases that might seem foreign to people outside of the culture.

Norms

Norms are the standards and expectations of behaviour. It is how people within a culture expect others to behave in different situations.

These expectations can be formal, like laws and codes that are enforced, or informal customs and standards that, while still considered important, are not enforced.

An interesting cultural norm amongst Wellington public transport users is the practice of thanking the bus driver. At each stop on a bus route, the phrase 'Thanks, driver' can be heard multiple times from exiting passengers.

In many western cultures, eye contact while speaking is considered an act of respect; while in some Pacific cultures, direct eye contact can be regarded as disrespectful.

Values

Every culture has values. They help members judge what is right or wrong, good or bad, desirable or undesirable. The values help to shape the norms.

In many western cultures, individualism is highly valued. 'Become independent', 'standing on your own two feet', 'looking out for number one' are examples of phrases that might have a positive meaning in these cultures.

Other cultures value the group, the community and the family higher than the individual. You might see extended families living together, younger members taking more responsibility for their siblings, and multi-generational households.

Attitudes towards work, education and the environment are all influenced by cultural values.

Artefacts

Artefacts are physical objects that have significance to a culture. We often think about artefacts in relation to ancient civilisations. We imagine archaeologists digging them out of the ground in places like Egypt.

All cultures have artefacts. The carvings that adorn a Maere (meeting house), or the greenstone taonga gifted to Iwi/tribe members, are examples of artefacts.

If you talk to people involved in car cultures, you may recognise some of their artefacts: turbochargers, spoilers, 10mm sockets.

Examples of cultural appropriation

Over the years, there have been many examples of cultural appropriation. The examples are often highlighted by an imbalance of power and a lack of respect for the victimised culture.

In December 2019, Princess Cruises issued an apology after members of the crew from one of its ships visiting Tauranga dressed in grass skirts and danced with black marking drawn on their faces while ushering passengers on and off the ship ('Cruise company apologises after staff pose as Māori for traditional welcome', 2019).

These crew members had appropriated elements of Māori culture. The use of traditional dress and performing dance without consultation with local iwi was condemned as culturally insensitive.

Ta moko–traditional Māori tattooing, often on the face–is a taonga (treasure) to Māori for which the purpose and applications are sacred (Ta moko - significance of Māori tattoos, n.d.). Applying facial markings to mimic traditional ta Moko is an example of cultural appropriation.

You can read more about this incident here.

Blackface? This one is pretty obvious. Do not do it! Blackface became popular in the US after the Civil War as white performers played characters that demeaned and dehumanised African Americans.

In recent years, many prominent political leaders, actors, and entertainers have come under fire for their use of blackface while attending public and private events in their past.

Blackface is a very overt form of cultural appropriation. More subtle forms of similar types of appropriation might include using a model of different ethnicity from the one portrayed or emphasising a cultural stereotype to make a point in an ad.

Lingerie brand Victoria Secret has been accused of and apologised for cultural appropriation on several occasions--most famously in 2012 when model Karlie Kloss wore a feather headdress that was clearly appropriated from Native American culture. The suede fringe, turquoise jewellery and leopard-print accents all highlighted a link to Thanksgiving. The outfit was perceived to glamorise the genocide Indigenous people experienced at the hands of European settlers and American colonists (Anderson, 2020).

Never trivialise sacred artefacts or symbols. Using artefacts and symbols in ways that do not honour or respect them to the same extent that would be expected within their own culture is another sign of cultural appropriation.

In 2016, an Auckland brewery used images depicting 'sacred' ancestors of Te Arawa (the leading tribal group of Rotorua and surrounding areas) on their beer bottles.

Rotorua kaumatua (elder) Paraone Pirika described the representations of his ancestors as culturally insensitive and severely misrepresentative. The association with alcohol was also not appreciated (King, 2016).

My tipuna knew nothing about alcohol and the effects of alcohol when they were alive, many moons ago.

Paraone Pirika

In 2018, a Belgium beer brewery labelled one of its beers 'Māori Tears'. Māori rights advocate Karaitiana Taiuru said the beer was another classic example of a brewery that is causing offence and 'The idea of drinking someone else's tears is spiritually offensive to a traditional Māori worldview' (Fitzgerald, 2018).

In 2020, a Canadian brewery and a New Zealand leather store made similar blunders by misusing the Māori word 'huruhuru' which can be translated to mean feathers or fur; however, it is more commonly used in reference to pubic hair (Anderson, 2020).

Avoiding cultural appropriation

The best way to avoid cultural appropriation is to engage meaningfully and authentically with the culture you are borrowing from.

Take the time to learn about and truly appreciate a culture before you borrow or adapt elements of that culture. Learn from those who are members of the culture, visit venues run by members of a culture (marae), and attend authentic events (powhiri, tangi, kapa haka) (Cuncic, 2020).

Ask permission, give credit and recognise the origin of elements that you borrow from other cultures rather than claiming to be original ideas.

My Culture

Our culture helps us understand who we are and what is important to us. You could define your culture by looking at your family, your friends, the places you grew up, the people you look up to and things you value most.

Your task is to try to define the elements of your culture.

Regarding your culture, what are the:

- symbols

- language

- norms

- values

- artefacts?

Create a list of your cultural elements, produce a mood board using canva.com or Adobe software, and if you feel comfortable doing so, share your culture in the forum.

Is there anyone in the learning community with a similar culture to yours? Are there any shared elements between your culture and another?

In this topic, we introduced Te Tiriti o Waitangi, including the historical context and significant differences between the te reo Māori and English versions.

The simplified principles (3Ps) can be a helpful framework for understanding how to apply Te Tiriti o Waitangi to work and life.

- Partnership: Acknowledges sovereignty/governance and working together with the same rights and benefits as subjects of the Crown.

- Protection: Acknowledges the protection of rights, benefits, possessions, tikanga, and taonga.

- Participation: Acknowledges sovereignty and governance. Ensuring equal participation at all levels and that Māori have input into decision-making directly affecting them.

We looked at cultural appropriation. What it is, some examples, and how to avoid it.

Additional resources

Here are some links to help you learn more about this topic.

It is expected that you should complete 12 hours (FT) or 6 hours (PT) of student-directed learning each week. These resources will make up part of your own student-directed learning hours.

- The Aotearoa History Show - Episode 3: Early Encounters

- The Aotearoa History Show - Episode 4: Te Tiriti o Waitangi

- Māori Dictionary

- Māori typeface and design