Investments are the processes of evaluating, determining and selecting the appropriate assets to achieve the required rate of return. Risk management and portfolio holding are some of the most common techniques used by investment analysts. In this topic, the focus is on the valuation and selection of financial assets. Common financial asset classes include shares, bonds, real-estate trust, infrastructure securities and financial derivatives. Essentially, the processes of investments are the same processes to facilitate the cash flows from social surplus units to the shortage units and, in return, the interests or financial claims will be paid by the applicating units. The financial institutions are the main market facilitators that enhance these transactions, while the different financial markets provide the trading systems and settlement mechanism to complete the transactions efficiently.

Welcome to Topic 4: Investments. In this topic, you will learn about:

- Concepts and practices of interest rates

- Shares and bonds

- Securities and markets

- Other investment vehicles.

These relate to the Subject Learning Outcomes:

- Understand the role of the finance and accounting functions in an organisation.

- Apply mathematics of finance to determine risk, return, evaluation of investment, financing, working capital and distribution decisions.

- Develop analytical skills drawing from key finance theories, concepts, and techniques.

Welcome to your pre-seminar learning tasks for this week. Please ensure you complete these prior to attending your scheduled seminar with your lecturer.

Click on each of the following headings to read more about what is required for each of your pre-seminar learning tasks.

Read the following textbook chapters of the prescribed text - Melicher, RW & Norton, EA 2017, Introduction to finance: Markets, investments, and financial management, 16th edn., John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

- Chapter 7 (pp. 45-54)

- Chapter 8 (pp. 190-191)

- Chapter 10 (pp. 252-260 & pp. 262-274)

- Chapter 11 (pp. 298-313 & pp. 320-327)

Read the following journal articles:

- Li, W, Rhee, G & Wang, SS 2017, ‘Differences in herding: Individual vs. institutional investors’, Pacific-Basin Finance Journal, 45:174-185.

- Shleifer, A & Vishny, RW 1986, ‘Large shareholders and corporate control’, Journal of Political Economy, 94:461-488.

- Fama, EF & French, KR 1992, ‘Common risk factors in the returns on stocks and bonds’, Journal of Financial Economics, 33:3-56.

Identify the key takeouts from the articles and add these to your reflective journal. You can access the reflective journal by clicking on ‘Journal’ in the navigation bar for this subject.

If you are unsure of any concepts, reach out to your lecturer.

Read the following web articles:

- Investor Daily, Blog.

- Langager, C 2022, How to start investing in stocks: a beginner's guide, Investopedia.

Read the journal article, 'Mortgage debt and entrepreneurship', then consider Discussion question 3 on p. 184 of the prescribed text.

Make note of your answers in your reflective journal and be ready to share your reflections with the class during the scheduled seminar.

This topic has discussion forum activities, which will enhance your knowledge and give you the opportunity to interact with your peers. You can access the activities by clicking on the following links. You can also navigate to the forum by clicking on 'FIN100 Subject Forum' in the navigation bar for this subject.

Read and watch the following content.

Interest rate

Interest rate is “the price of loanable funds in financial markets. The price that equates the demand for and supply of loanable funds in the financial markets” (Melicher & Norton 2017, p. 191). The exchange process of funds in the market should always be traded at an equilibrium price and the interest rate will act as a synchronisation factor for the money markets’ supply and demand.

For example, the interest rate might move from an existing equilibrium towards a higher or lower equilibrium. Some factors may affect the demand side of the market funds, such as economic recovery after the historical financial crisis. More companies and households would require capital to invest or expand the operating businesses. This will push the general demands of the funds up as a consequence. If the supply sides of the capital could not increase accordingly, the new equilibrium price of the funds will increase in terms of interest rates. The shift of the general interest rates in the market is a dynamic movement. Influential factors like the economic cycle, inflation, monetary policy and fiscal policy will be possible driving forces.

Before discussing investments further, it is necessary to first examine some brief monetary histories of interest rates. Compare the following two (2) figures, which show the changes in interest rates over time in the United States of America and Australia, respectively.

Use this link to examine the interactive chart of Federal Funds Rate - 62 Year Historical Chart.

These are the long horizon histories of both countries from the economic period after World War II. It is easy to observe the trends of increasing interest rates after World War II from the data of both countries. The primary reason for the increase in interest rates was the gradual recovery of the economy from the war damage – the increased volume of trading and investing activities pushed the rate up with strong demand support.

Looking at trends in the 1980s, emerging policies, such as decentralisation of the financial institutions, led to the downwards tendency of the interest rate, and this easing process of the market rate was maintained until the beginning of 21st century. In summary, the interest rate of a country has widely been regarded as the indicator of the domestic monetary policies and economic environments.

Main financial instruments of investments

From the corporate perspective, equity financing and debt financing are two (2) major sources of capital. As a modern global company, the financial instruments to facilitate these financing activities are shares and bonds. These two (2) main financial and trading vehicles have attracted great transactional interests from global institutional and individual investors.

Bonds

A bond is “an agreement or contract between lenders and the borrowing organisation; typically, a firm or government body” (Melicher & Norton 2017, p. 255). The issuing bodies of the bonds is generally attributed to corporations or governments.

Corporate bonds

A corporate bond is a legal contract that defines both the rights of the bondholders and the obligations of the corporate issuers. There are specific definitions of the face value, time to maturity, coupon payment rate and related legal regulations. Commonly, the issuing company should:

- Appropriately maintain accounting records in accordance with generally accepted accounting principles (GAAP)

- Periodically supply audited general auditing reports

- Pay related taxations and other liabilities when due

- Maintain all facilities in good working order (Melicher & Norton 2017, p. 255).

The common elements of bonds are as follows:

- “Represent borrowed funds

- Contractual agreement (indenture) between a borrower and lender

- Senior claim on assets and cash flow

- No voting rights

- Par value

- Having a bond rating improves the issue’s marketability to investors

- Covenants

- Interest:

- Tax deductible to the issuing firm

- Usually fixed over the issue’s life but can be variable if the indenture allows coupon rate to be affected by market interest rates and/or bond rating

- Maturity:

- Usually fixed; can be affected by convertibility, call and put provisions, sinking fund, and extendibility features in the indenture

- Security:

- Can have senior claim on specific assets pledged in case of default or can be unsecured (debenture or subordinated [junior claim] debenture)” (Melicher & Norton 2017, p. 255).

Large global companies are always the active participants in the bonds market, as both the issuers and investors. Examples include mature companies in various industries such as Microsoft, Apple, Coca-Cola, BHP and Airbus. They regularly issue the bonds for debt financing with different time to maturity, some as long as 30-years. On the other hand, they also invest in other companies’ bonds as bondholders to diversify their own investment portfolios.

Government bonds

Another principal player in this fixed-income security market is the government. The bond market is more important for the monetary and fiscal significance of governments than the share market because the domestic government has limited access to finance through the equity. The treasury department usually plays a vital role to issue the treasury bills or bonds representing the financial authority from the national government. For example, the United States Department of the Treasury has a regular TreasuryDirect program to sell the treasury securities directly to individual investors. Institutional investors such as pension funds and insurance companies are the likely holders of these treasury securities for their investment purposes.

How could investors in the bonds market know the reputation, trading and default history or general risk level of these investments? There are several independent agencies to provide credit information related to the security issuer. ‘Credit rating’ or ‘credit ranking’ is the categorised ranking service provided by agencies such as Standard & Poor’s (S&P), Moody’s and Fitch. These institutes generate their rankings by applying the ratio and cash flow analysis to test the issuer’s ability to meet the debt payments of interests and principals. The following table demonstrates the rating system applied by Moody’s:

| Categories | Rating symbols | Rating notches | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|

| Investment | Aaa | Highest quality, subject to the lowest level of credit risk | |

| Aa | Aa1 |

High quality, subject to very low credit risk |

|

| Aa2 | |||

| Aa3 | |||

| A | A1 |

Upper-medium grade, subject to low credit risk |

|

| A2 | |||

| A3 | |||

| Baa | Baa1 |

Medium-grade, subject to moderate credit risk and may possess certain speculative characteristics |

|

| Baa2 | |||

| Baa3 | |||

| Speculative | Ba | Ba1 |

Judged to be speculative, subject to substantial credit risk |

| Ba2 | |||

| Ba3 | |||

| B | B1 |

Considered speculative, subject to high credit risk |

|

| B2 | |||

| B3 | |||

| Caa | Caa1 |

Speculative of poor standing and subject to very high credit risk |

|

| Caa2 | |||

| Caa3 | |||

| Ca | Speculative and likely in, or very near default, with some prospect of recovery of principal and interest | ||

| C | The lowest rated and typically in default, with little prospect for recovery of principal or interest |

Shares

Shares represent the ownerships of the corporations as the financial certificate hooded by investors. This financial security is traded publicly in the stock exchange according to the present market price. In the short term, the open market price is determined by the supply and demand inquiries from investor groups. The ownerships of companies are exchanged from sellers to buyers during the process of trading. There are two (2) major types of shares:

- Common shares

- Preferred shares.

Common shares

Common shareholders represent the larger percentage of ownership from a company. Common shareholders represent the limited liability of the ownership due to the nature of the modern corporation system. There is a financial guarantee that they cannot lose more than the percentage they have contributed to the company’s capital. With the claiming right they have, common shareholders expect to be compensated with profit-based dividends and, ultimately, significant capital gains.

Common shareholders also have voting rights to elect the board of directors at the annual meeting. To represent shareholders’ benefits, the board of directors will exercise the general controlling power for the company’s daily business.

The key elements of common shares include:

- “Represents an ownership claim

- Board of directors (board) oversees the firm on behalf of the shareholders and enforces the corporate charter

- Voting rights for board members and other important issues allowed by the corporate charter

- Lowest claim on assets and cash flow

- Par value is meaningless, and many firms have low or no-par stock

- Dividends:

- Received only if declared by the firm’s board

- Paid out from after-tax earnings and cash flow; not tax deductible

- Dividends are taxable when received by the shareholder

- Can vary over time

- Maturity:

- Never; stock remains in existence until firm goes bankrupt, merges with another firm, or is acquired by another firm” (Melicher & Norton 2017, p. 267).

Preferred shares

Preferred shares are the equity security that are given preference for the company’s profit and liquidated assets over common shares. The regular dividend payments are received by the preferred shareholders and the fixed amount of these dividends are usually pre-determined in the legal contract. For example, a preferred share may receive a 6 % dividend payout during the regular financial year, which means they receive 6 % out of the face value of the share as cash or a cheque.

With some significant differences from common shares, the key elements of preferred shares are as follows:

- “Does not represent an ownership claim

- No voting rights unless dividends are missed

- Claim on assets and cash flow lies between those of bondholders (specifically, subordinated debenture holders) and common shareholders

- Par value is meaningful as it can determine the fixed annual dividend

- Dividends:

- Annual dividends are stated as a dollar amount or as a percentage of par value

- Received only if declared by the firm’s board

- Are paid out from after-tax earnings and cash flow; not tax-deductible

- Taxable when received by the shareholder

- May be cumulative

- Maturity:

- Unless it has a callable or convertible feature, the stock never matures; it remains in existence until firm goes bankrupt, merges with another firm, or is acquired by another firm” (Melicher & Norton 2017, p. 268).

The face value of preferred shares is more important than for common shares because the dividend payouts for preferred shares are calculated based on it. The dividend payouts for common shares are ultimately determined by the policies made by the company’s management. The actual amount may change due to the level of profitability every financial year. Consequently, the riskiness of return from common shares is always higher than the preferred shares of the same company, which could be reflected in the general rates of return of both.

Securities and markets

Primary markets and Initial Public Offering (IPO)

The concept of the primary market was introduced, in Topic 2, as the issuing market for financial instruments such as bonds and shares. Technically, the initial sale of newly issued bonds or shares is named as the process of flotation. Specifically, the initial issuing of the shares is called Initial Public Offering (IPO) from the financial market professionals.

After successful developments of the business, fast-growing private companies will have a large demand for capital, and the most effective and stable choice to achieve this would be ‘going public’. These IPOs are usually assisted by financial intermediaries, such as investment banks, to fulfill the pre-IPO marketing and effective valuation of the issuing price. Some examples of investment banks include Morgan Stanley, Goldman Sachs and Citi Group.

The main information related to the IPO is described in a document named the prospectus. The information includes basic financial statements, the marketing process before IPO and other important disclosures from management.

The duration of the entire IPO process typically lasts for one (1) year or more, according to the requirements of the capitalisation. The market timing of the IPO has always played a crucial role in attracting sufficient equity funds to the process. In an active and efficient market, the equity capital generated through the IPO process could be twice or several times higher than the original planning figure. On the other hand, if the market at the time is weak in terms of trading activities, the company may even fail to raise enough funds to meet the initial expectation. It is fair to say an efficient and active secondary market has provided the source of liquidity to enhance the functionality of the primary market.

Secondary markets and trading securities

After the IPO process, all trading activities and exchange behaviours of the shares are facilitated by the secondary markets or the stock exchange. In contemporary practice, there are two (2) components that make up the marketplaces of the exchange:

- Organised securities exchange (with a physical trading floor)

- Over-The-Counter (OTC) market.

The trading activities of OTC are organised by computer networking via internet connection or digital equipment like mobiles or electronic pads. For example, the New York Stock Exchange is mainly a physical trading exchange located on Wall Street, New York, while the NASDAQ is operated as an OTC market.

How can the average daily performance be measured for general public investors? The answer is the market index.

Market indexes

The listed trading securities are several thousand in number in one (1) common stock exchange. The market index is the weighted average result of the prices from a sample collection. For example, the Dow Jones Industrial Average (DJIA), a well-known stock market index with almost the longest historical records, is calculated by averaging the daily prices of 30 large organisations whose market capitalisation (the number of shares multiplied by the stock price) is compared to those of other large organisations. Market indexes are very well-developed indicators typically used to observe the performance of any particular market.

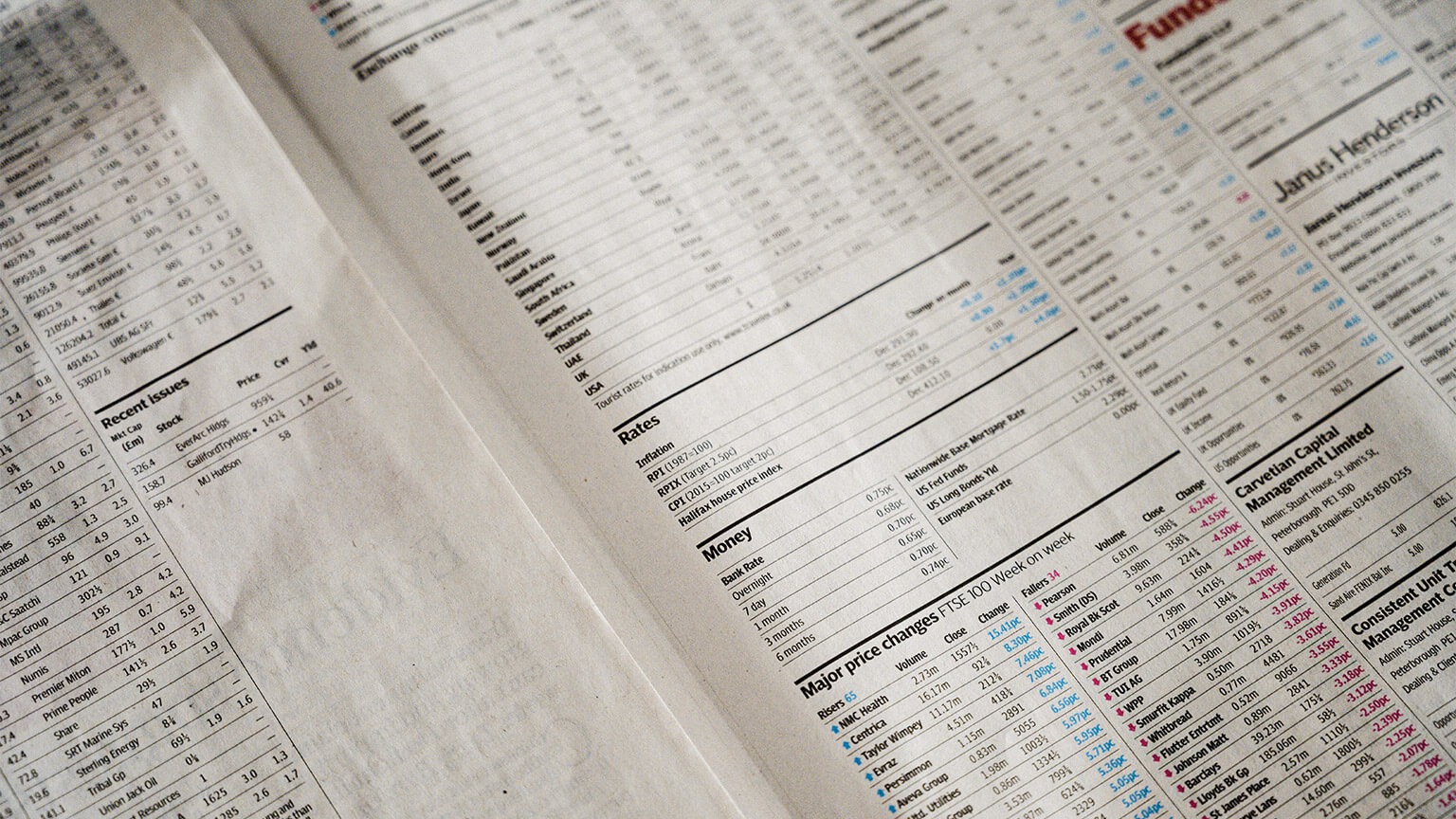

Why are these indexes so popular? First of all, they are an efficient symbol representing the average movement of and returns to the overall market. The DJIA 30, S&P 500, FTSE 100 and Nikki 225 are all comprehensive measures of different regional share markets. Every modern stock market in the world has developed their own applicable index to reflect the daily information of the performance of that market.

Secondly, indexes are a useful benchmark to compare with your constructed investment portfolio. If your financial advisor recommends a portfolio of shares that provide 10 % as the annual return while the S&P 500 has achieved 20 % in that year, you may feel like this is a poor choice.

Last but not least, indexes themselves might be a brilliant investment portfolio. Rather than investing to ‘beat the market’, in the long term, statistical evidence has persuaded smart investors to ‘follow the market’. Passive fund managers choose to invest in the shares and bonds with the expectation of matching the index's performance over time. This strategy has made the passive funds winners in the long run (more than ten (10) years horizon) against the active peers.

Key takeouts

Congratulations, we made it to the end of the fourth topic! Some key takeouts from Topic 4:

- Interest rates are determined by the demand and supply of loanable funds in the money market.

- Debt financing involves borrowing money whereas equity financing is selling a percentage of the equity in the company.

- High risk, uncertain projects are better off to finance via equity.

- Passive investors tend to hold their portfolios for a longer time to get the best possible return.

Welcome to your seminar for this topic. Your lecturer will start a video stream during your scheduled class time. You can access your scheduled class by clicking on ‘Live Sessions’ found within your navigation bar and locating the relevant day/class or by clicking on the following link and then clicking 'Join' to enter the class.

Click here to access your seminar.

The following learning tasks will be completed during the seminar with your lecturer. Should you be unable to attend, you will be able to watch the recording, which can be found via the following link or by navigating to the class through ‘Live Sessions’ via your navigation bar.

Click here to access the recording. (Please note: this will be available shortly after the live session has ended.)

In-seminar learning tasks

The in-seminar learning tasks identified below will be completed during the scheduled seminar. Your lecturer will guide you through these tasks. Click on each of the following headings to read more about the requirements for each of your in-seminar learning tasks.

Watch the video, Warren Buffet’s 6 Rules of Investing.

Working in a breakout room team assigned by your lecturer during the scheduled seminar, discuss the following questions with your teammates. Your lecturer will request that you present the findings back to the class.

- Who is Warren Buffet and what are his investing achievements?

- What are the six (6) rules of investing as outlined by Warren Buffet?

- What is the definition of fundamental analysis and how does Warren Buffet apply it?

- How could the rules and experiences from Warren Buffet affect your investment decision?

- Working in the same breakout room as previously, visit the Morningstar (a financial service company) website.

- Go to the top menu and click ‘Stocks’. Select a stock story to read the information and details.

- Share and discuss your findings with your teammates. Use the following questions to guide your discussion:

- Which share or company have you selected?

- Briefly introduce the background of the business.

- Which industry does the company belong to?

- How could the information in the contents affect your investing viewpoint with the company?

Welcome to your post-seminar learning tasks for this week. Please ensure you complete these after attending your scheduled seminar with your lecturer. Your lecturer will advise you if any of these are to be completed during your consultation session. Click on each of the following headings to read more about the requirements for each of your post-seminar learning tasks.

Complete the following review question from the prescribed text (Melicher & Norton 2017) – p. 215 and add your answer in your reflective journal.

“How can a change in the money supply lead to a change in the price level?”

Work in a breakout room as assigned by your lecturer during the consultation session:

- Select one (1) definition from ‘Key Terms’ at the end of Chapter 8 of the prescribed textbook.

- Discuss the definition of the key term you have selected and prepare a 5-minute presentation using a visual tool of your choice (for example, PowerPoint or Canva).

- Your group will present the financial term to other candidates during the scheduled consultation time.

Knowledge check

Complete the following five (5) tasks. The following questions have been adapted from p. 270 of Melicher, RW & Norton, EA 2017, Introduction to Finance: Markets, Investments, and Financial Management, 16th edn., John Wiley & Sons Inc.

Click the arrows to navigate between the tasks.

Please ensure you complete Assessment 2, Quiz 3 by the nominated time and date. You can access this quiz by clicking on “Assessment 2” in the navigation bar for this subject, then selecting “Quiz 3 – Week 4”.

Each week you will have a consultation session, which will be facilitated by your lecturer. You can join in and work with your peers on activities relating to this subject. These session times and activities will be communicated to you by your lecturer each week. Your lecturer will start a video stream during your scheduled class time. You can access your scheduled class by clicking on ‘Live Sessions’ found within your navigation bar and locating the relevant day/class or by clicking on the following link and then clicking 'Join' to enter the class.

Click here to access your consultation session.

Should you be unable to attend, you will be able to watch the recording, which can be found via the following link or by navigating to the class through ‘Live Sessions’ via your navigation bar.

Click here to access the recording. (Please note: this will be available shortly after the live session has ended.)

- Elton, EJ, Gruber, MJ & Busse, JA 1998, ‘Do investors care about sentiment?’, The Journal of Business, 71(4):477-500.

- Intelligent Investor 2022, Intelligent Investor, InvestSMART Financial Services Pty Ltd.

- Investment Magazine n.d., Investment Magazine, Investment Magazine.

- Kang, J, Luo, J & Na, HS 2018, ‘Are institutional investors with multiple blockholdings effective monitors?’, Journal of Financial Economics, 128(3):576-602.

- Tracy, P 2021, Benjamin Graham: The Father of the value Investing, Investing Answers.

References

- Atlas magazine 2018, Moody’s rating scale, https://www.atlas-mag.net/en/article/moody-s-rating-scale

- Bracke, P, Hilber, CAL & Silva, O 2018, 'Mortgage debt and entrepreneurship', Journal of Urban Economics, 103:52-66, https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0094119017300827

- De Bondt, W & Thaler, R 1984, ‘Does the stock market overreact?’, The Journal of Finance, 40(3):793-805.

- Douglas, D & Philip D 2000, ‘Bank Runs, Deposit Insurance, and Liquidity’, Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis Quarterly Review, 24(1):14-23.

- EY global 2018, Global banking outlook 2018, Streaming video, YouTube, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZPDb9eTStSE

- Fama, EF & French, KR 1992, ‘Common risk factors in the returns on stocks and bonds’, Journal of Financial Economics, 33:3-56.

- Kerin, J 2021, Buffett vs. Soros: Investment strategies, Investopedia, https://www.investopedia.com/financial-edge/0912/buffet-vs.-soros-investment-strategies.aspx

- Li, W, Rhee, G & Wang, SS 2017, ‘Differences in herding: Individual vs. institutional investors’, Pacific-Basin Finance Journal, 45:174–185.

- Melicher, RW & Norton, EA 2017, Introduction to finance: Markets, investments, and financial management, 16th edn., John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

- Netflix 2020, Explained: The Stock Market, Streaming video, YouTube, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZCFkWDdmXG8&t=69s

- Shleifer, A & Vishny, RW 1986, ‘Large shareholders and corporate control’, Journal of Political Economy, 94:461-488.

- Simon, J 2015, Low interest rate environments and risk, https://www.rba.gov.au/speeches/2015/sp-so-2015-10-08.html

- Tobin, J 1982, ‘The Commercial Banking Firm: A Simple Model’, Scandinavia Journal of Economics, 84(4):495-530.