About this Module.

In this module, you will study the factors affecting supply and demand for tourism destinations and products as well as the New Zealand national tourism marketing strategy. These will be covered in the following topics:

- The Tourism Product

- New Zealand National Tourism Marketing Strategy

Using this knowledge, you will apply your understanding to analyse the national tourism marketing strategy.

Details

| Expected Duration | Credits | Level | Assessments |

|---|---|---|---|

| 150 hours | 15 | 5 | 2 |

Outcomes

| Graduate Profiles | Learning Outcomes | Assessment |

|---|---|---|

|

GPO 3 Analyse and evaluate local, national, and international tourism operating environments in order to facilitate rational decision-making in the tourism industry |

LO3.2 Critique the national tourism marketing strategy and key objectives for the promotion of Aotearoa New Zealand as a tourism destination to guide decision making in tourism organisations (5 Cr) LO 3.1 Analyse factors influencing the supply and demand of tourism products and destinations in New Zealand to inform decision making in the tourism industry (10 Cr) |

|

Welcome to The New Zealand Tourism Industry module which gives you some insight into the economic concepts of demand and supply and the factors which influence tourism products and destinations. In this module, we will study:

- New Zealand tourism industry organisations and their strategies

- The New Zealand Tourism Sustainability Commitment

- The nature of tourism (the tourism product)

- The factors influencing the demand and supply of tourism product

- Destination management

You have already encountered New Zealand’s National Tourism Organisation (NTO) during the Marketing module, and we will further investigate their key objectives and strategies enabling you to offer a critique of their tourism destination management.

But before we begin, we should have an understanding of how the New Zealand tourism industry evolved from zero to hero!

![[ADD IMAGE'S ALT TEXT]](/sites/default/files/Chateau%20Hotel.jpg)

Note: When you see this icon in this module, download or click on your speech-to-text plug-in. If you haven't already downloaded it, do so here.

![]() Activate Now!

Activate Now!

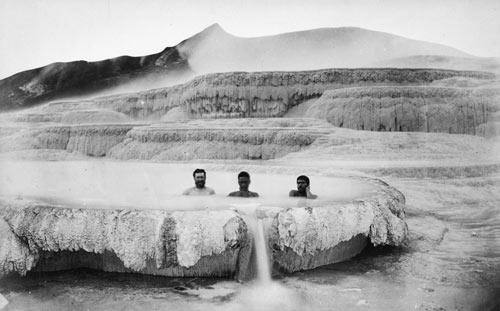

The first early tourists to New Zealand were wealthy travellers from Britain and the United States who ventured here in the mid-19th century. In those days, they came to see the mountains, forests, lakes, and geysers in a time when New Zealand became known as ‘the wonder country’. The highlights were Milford Sound, the Whanganui River, and the thermal area of Rotorua- known as ‘the Hot Lakes District’ where the chance to see Māori people and their unique culture was an added attraction. In the 1840s, the Pink and White Terraces at the northern end of Lake Rotomahana, (near Rotorua) were the flavour of the day and became known as “the eighth wonder of the world”. Their reputation drew visitors to bathe in the pink waters of Te Otukapuarangi (Pink) Terraces and visit the Te Tarata (White) Terraces. It would have been an incredible sight, the geothermal waters flowing out of the ground swept down into pools, the minerals crystallising and forming pink and white terraces with tumbling waterfalls and pools where they could bathe.

Just getting to the terraces was an ordeal for the tourists. They made their way by horse-drawn coaches from Auckland, Maketu, or the Whanganui River and arrived at Rotorua. They stayed here to rest and stay at one of four basic hotels in Ohinemutu before travelling onwards around 40 km by horse and cart across hills, and then two hours further by canoe and finally on foot to arrive at the natural masterpiece. Te Arawa hapu Tūhourangi were tangata whenua of the terraces and they were the first to host New Zealand’s influx of tourists. (Sole, 2006)

The Birth Of Māori Tourism

It was the local Māori women who were hired as the first tourist guides. One such guide was Sophia Hinerangi-Gray, also known as Guide Sophia, who was a respected role model in her community. She won the hearts of international visitors with her quiet grace, intelligence, and manaakitanga and became a very sought-after guide. She not only worked as a tour guide but successfully managed her whanau and iwi commitments simultaneously, which was very rare in those days. She worked hard and encouraged local women to become financially independent.

The Tūhourangi iwi that controlled access to the Pink and White Terraces displayed a sign at Te Wairoa, (the nearest village settlement to the terraces) which set out the fees for guides and transport to the attraction. The wealth generated by this early tourism saw the pāua shell eyes featured on local carvings replaced by gold sovereign coins! (Diamond, 2010)

The volcanic eruption of Mt. Tarawera, in 1886, lasted 6 hours and not only completely obliterated the terraces but nine villages nearby too. The official death toll was 153 but an unknown number of Māori in other nearby villages also died. After the eruption and the loss of the Terraces and their homes, many locals were driven to leave the devastated area and relocate to Whakarewarewa Thermal Village (also near Rotorua). This went on to become one of the most popular visitor destinations across New Zealand and descendants of those early guides, such as Guide Sofia, are still guiding tourists today.

![[ADD IMAGE'S ALT TEXT]](/sites/default/files/Horonuku%20Te%20Heuheu.jpg)

Māori acted as guides in other regions too. The glow worm caves at Waitomo became another area that fascinated the tourists and they ferried tourists up and down the Whanganui River, which was known at the time as the Rhine of New Zealand.

Ngāti Tūwharetoa iwi also played a role in the beginnings of tourism in the Central North Island. The Tūwharetoa region stretches from the Tarawera River across to the lands around Mount Tongariro and Lake Taupō. Following the New Zealand wars of the 1860s, Taupō started to develop as a tourist destination but the businesses serving the tourism were mainly controlled by former Pakeha soldiers as opposed to local iwi.

The main chief of Tūwharetoa iwi, Horonuku Te Heuheu, made an agreement with the government back in 1887 around the lands which included Tongariro, Ngaūruhoe and Ruapehu mountains. This became the basis of the Tongariro National Park which was established a few years later in 1894. Iwi involvement in the management of the park was minimal and despite repeated requests for iwi recognition, it was many years before Horonuku’s deed was displayed and acknowledged. Tongariro National Park is today one of New Zealand’s most iconic national parks and is a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

The Beginnings Of A National Tourism Organisation

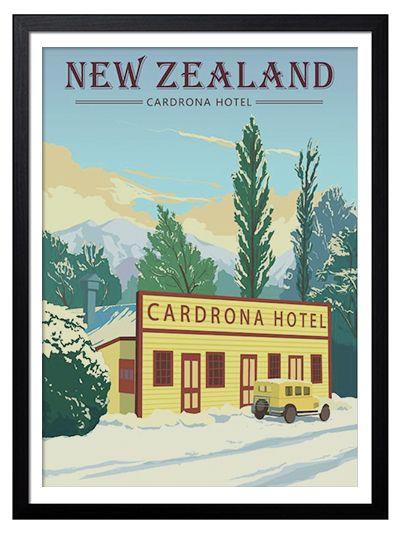

Just over 120 years ago, when tourism was a fledgling industry, the then Prime Minister, Sir Joseph Ward, had the foresight to recognise the potential benefits to the country and created a department to develop the business of tourism. He realised that the government could and should play a significant role in supporting tourism throughout the regions. In the late 19th century, the government took control of several tourist sites including The Milford Track and Rotorua’s thermal pools along with hotels and accommodation houses near Lake Waikaremoana, Waitomo, Lake Pūkaki, Te Anau, and again Rotorua. You will recognise these as prime tourism locations, and the 1st of February 1901 witnessed a world first, the Department of Tourist and Health Resorts was launched right here in New Zealand. The world’s first official government tourism office was established specifically to support and develop tourism. This was the beginning of New Zealand’s National Tourism Organisation (NTO), better known today as Tourism New Zealand, (TNZ).

The first recorded figures show that 5233 international visitors arrived in 1903. You will remember the global tourism operating environment of the 20th century and the advancements in transport technology dramatically changed the face of tourism. By the time pre-Covid annual figures were published for 2019, almost 3.9 million international visitors arrived in New Zealand. (Source: www.stats.govt.nz,2019.)

Important

Hotel standards were quite basic well into the 20th century. There were only four licensed hotels in Queenstown in 1950 and visitors were often expected to share rooms – or even a double bed – with strangers! The food was unvarying and dull and often diners at even the plushest of hotels, such as Wellington’s Waterloo, were made to rush through their meal by 7.00 pm to keep down staffing costs.