Animal behaviour refers to the actions, reactions and patterns of movement exhibited by animals in response to internal and external stimuli (events or conditions). Animal behaviour encompasses a wide range of activities, including communication, feeding, mating, territorial and resource defence, parental care, and social interactions.

Animal behaviour is influenced by various factors, such as genetics, health status, environmental conditions and learned experiences. Understanding animal behaviour provides valuable insights into an animal's physical and emotional state and can help explain and even predict how they will respond to other animals, people and their environment.

Each animal species, wild or domesticated, has evolved unique behaviours that enable them to survive and thrive in their particular environments. Additionally, different breeds of companion animal species often exhibit specific behavioural traits that have been selectively bred for over generations. For example, Border Collies are bred for working livestock and exhibit behaviours such as sudden bursts of speed, rapid changes of direction and slow creeping to influence the movement of livestock. In contrast, Cavalier King Charles Spaniels, as pictured in the following image, were bred as companion animals and are very gentle and affectionate.

Recognising and interpreting the various behaviours exhibited by different breeds and species is a key skill to have when working with a range of different animals.

How to identify a species or breed

Before you can start to identify and interpret behaviours, you first need to identify the species and breed of the animal you are working with. Once you know the species and breed, you can spot behaviours that are typical or unusual for that type of animal.

Most species and breeds have distinguishing physical features that will enable you to tell the difference between similar-looking animals. When working with wildlife, these characteristics are often called diagnostic features.

As your experience grows, so too will your ability to identify species and individual breeds. However, until you become familiar with the common animals at your workplace, you will likely need to refer to the documentation for diagnostic features, physical characteristics and common behavioural traits associated with each species and breed.

Identification documents

Common types of identification documentation include field guides and breed standards.

Field guides

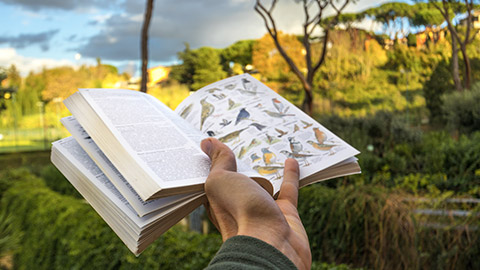

Field guides are commonly used to identify wildlife species. They typically provide detailed descriptions, illustrations, photographs, and relevant information about the physical characteristics, habitats, behaviours, and distribution of the species they cover. They provide concise and easily accessible information to help identify the species of an animal, including how to distinguish between very similar-looking species.

Field guides tend to focus on a particular group of animals found within a set geographic area. For example, all Australian birds, the mammals of NSW or the frogs of the greater Perth region. Species are usually ordered in the field guide according to evolutionary relatedness. In other words, the more closely related species will be grouped together.

Breed standards

Breed standards are a set of guidelines and criteria that define the ideal characteristics, appearance, temperament, and function of a specific breed of animal. Breed standards are primarily used for cats, dogs and horses. These standards serve as a blueprint for breeders, judges and enthusiasts to maintain and evaluate the integrity and consistency of a particular breed. However, they also help to identify the specific breed of an animal because they specify the physical attributes, such as size, shape, coat type, colour and pattern, as well as behavioural traits and performance abilities that are desirable for the breed.

To identify a species or breed using field guides or breed standards, compare the features described in the document with the animal in front of you. It is important to read the information carefully and interpret the descriptions accurately. Until you become more familiar with different species and breeds, it may take a few trial-and-error attempts to locate the correct species or breed within the document. If you are not confident with your identification of species or breed, confirm it with a more experienced staff member.

Animal records

An animal record should also contain information about the individual’s identity. Many animal records will include a written description of the animal as well as a photograph. It is important to be familiar with the industry terminology used to describe the physical attributes of different species and breeds. This includes the proper terms used for different types of coat markings or different coat colours. For example, Standard Poodles have a number of different coat colours, including apricot (pale red-tan), blue (diluted black) and silver (grey). Cavalier King Charles Spaniels can be black and tan, ruby (entirely red), Blenheim (chestnut and white) or tricolour (black, white and tan).

To identify an animal using the animal record, simply compare the written description and photograph (if there is one) with the animal in front of you.

Dichotomous keys

A dichotomous key is a tool used in biology to identify and classify organisms based on a series of paired, contrasting statements or characteristics. It is a systematic approach that allows users to make a series of choices or decisions about the organism's features, leading to a final identification.

Each pair of statements presents mutually exclusive options, such as yes/no or true/false, based on observable traits, including shape, colour and behaviour. By following the key and selecting the most accurate statement or characteristic at each step, the user can progress through a branching structure of choices until they reach a specific identification.

Dichotomous keys are most commonly used for identifying wildlife. However, they can also be written to identify the breed of a companion animal.

For example, the following is a very basic dichotomous that distinguishes between and identifies five different Australian mammal species.

- Does the mammal have a pouch?

- Yes. Go to question 2.

- No. It could be a Dingo (Canis lupus dingo).

- Does the mammal lay eggs?

- Yes. Go to question 3.

- No. Go to question 4.

- Does the mammal have sharp spines on its back?

- Yes. It could be a Short-beaked Echidna (Tachyglossus aculeatus).

- No. It could be a Platypus (Ornithorhynchus anatinus).

- Is the mammal small in size, weighing less than 1 kg?

- Yes. It could be a glider (genus Petaurus).

- No. Go to question 5.

- Does the mammal have distinctively large hind feet and a long, muscular tail?

- Yes. It could be a kangaroo (family Macropodidae).

- No. It could be a Koala (Phascolarctos cinereus).

Common animal families, species and breeds

The most common animals you will likely work with in the Animal Care Sector will be companion animals, particularly cats, dogs and aviary birds. However, you may need to interact with more exotic pets, such as reptiles, with rescued wildlife or even exhibited animals. While there are far too many animal species to discuss here, you will learn the key diagnostic features of some of the more common species and breeds you will likely encounter in the animal care industry.

In November 2022, Animal Medicines Australia reported that an estimated 28.7 million pets were housed across 6.9 million households in Australia. The majority of which were cats and dogs.

(In Australia) almost half of all households (have) at least one dog and a third of all households (have) at least one cat.Animal Medicines Australia, 2022

Some key physical differences between cats and dogs include:

- Domestic cat breeds are much more similar in shape and size than domestic dog breeds. For example, most cats have short, upright, pointed ears, while dogs have floppy or erect ears of varying lengths and shapes.

- Dog skeletons tend to be more robust (thicker and stronger) than cat skeletons. Conversely, cat spines tend to be much more flexible than those of dogs.

- Dog claws are blunt and do not retract, while cat claws are sharp, curved and can extend or retract as needed.

- Cats have sharp, pointed teeth, specialised for their carnivorous diet. On the other hand, dogs have a range of different-shaped teeth suited for a more omnivorous diet.

- Cats have rough tongues, vertically elliptical pupils and generally have warm, dry noses. Dogs have soft tongues, round pupils and generally have cool, wet noses.

Common dog breeds

Dogs are the most common companion animal in Australia, and with hundreds of pure breeds, plus all the crossbreeds and ‘bitzers’ (mongrel dogs of an unknown mix of breeds), there are plenty of different types to choose from.

When identifying the breed of a dogs you need to consider the following physical characteristics:

- Height at the withers (the ridge between the shoulder blades)

- Body conformation (the overall proportions of the dog, including relative lengths of the forequarters and hindquarters, length of back and length of neck)

- Coat length, colours, style (wavy or straight), texture and whether it is a double or single coat

- Head and muzzle shape

- Ear shape, size and position on the head

- Tail length and carriage (how the dog holds its tail).

Different countries and dog breed organisations recognise different numbers of breeds and categorise them differently. For example, the Dogs Australia, the most reputable organisation in Australia responsible for Registered Pure Bred dogs, currently (as of 2023) identifies 225 breeds of dog, organised into the following seven groups.

Note

Remember that when you are working in Australia, you must ensure you research dog breed information from the Dogs Australia breed standards so that your groupings are correct for this country.

Select each group heading to learn more about the group.

Breeds in the Toy Group are characterised by their small size. Dogs Australia lists 28 Toy breeds, including the Cavalier King Charles Spaniel, Chihuahua (Smooth and Long coat), Griffon Bruxellois (Smooth and Wire), Pug and Pomeranian.

The Pomeranian is a compact, short coupled dog (small distance between the last rib at the pelvis) with a thick, coarse, double-layered coat. The tail is a diagnostic feature of the breed and is carried straight over the back. The eyes are small and almond-shaped. The ears are also small and set high towards the top of the head. The muzzle is short and wedge-shaped, giving the dog an alert and ‘foxy’ expression (Friedman, 2016).

Terriers are dogs that were originally bred to hunt pest animals and vermin, such as rats, rabbits and even foxes. Dogs Australia currently recognises 31 breeds of Terrier. Well-known terrier breeds include the Airedale Terrier, Staffordshire Bull Terrier, Jack Russel Terrier, West Highland White Terrier and Fox Terrier.

The Airedale Terrier is the largest of the Terrier Group. A fit and healthy adult usually weighs 20-30 kilograms, and males are approximately 58-61 cm tall at the withers.

The outer coat is dense, stiff and wiry, while the undercoat is softer. The Airedale typically has a black saddle that extends over the back of their neck and the top side of the tail, while the rest of the body is tan.

The Airedale is inquisitive and appears calm and intelligent. The skull is long and flat, with the ears positioned in a V-shape. The neck is moderate in length, leading to long sloping shoulders, a short, straight back and strong, muscular hindquarters (Fittler, n.d.).

Gundogs are a category of hunting dogs, bred to retrieve game, typically birds, that had been shot by the hunter. There are 32 breeds of Gundogs currently recognised by Dogs Australia. These include setters (including the Irish Setter), pointers (such as the German Shorthaired Pointer), retrievers (for example, the Golden Retriever) and spaniels (such as the Springer Spaniel and Cocker Spaniel).

The Irish (Red) Setter has a characteristic glossy, deep red coat with feathery legs, chest, stomach and tail. The back slopes gently towards the hindquarters. Long and lean head with a moderately long, square muzzle and moderately sized ears, set well back on the head and hanging down neatly (The Kennel Club, 1994).

Dogs (males) typically weigh 33-35 kg and measure approximately 68-69 cm at the withers, while bitches (females) weigh approximately 27-30 kg and are 63-64 cm tall (The Irish Setter Association of NSW, n.d.).

Hounds were first bred to assist hunters in finding game by using their excellent sense of smell or sight. This group can be further divided into Sight Hounds and Scent Hounds.

Sight Hounds hunt using their acute vision. They are bred for speed and so have sprinter's bodies with long muzzles, deep chests and thin waistlines. They tend to bark less than other breed groups, have a greater sensitivity to anaesthesia and are more prone to bloat than other breed groups.

Scent Hounds hunt using their highly sensitive sense of smell. They are bred for endurance rather than speed. They typically have long muzzles and large nostrils, longer ears and tend to be stockier than Sight Hounds. However, the Scent Hound body shape is less uniform than the Sight Hound. Scent Hounds tend to have loud, booming voices and frequently bark or howl.

Dogs Australia list 37 breeds of Hounds, including the Rhodesian Ridgeback, Beagle, Bloodhound, Irish Wolfhound and Greyhound.

The Beagle is a medium-height hound, measuring between 33-40 cm at the withers. It is a sturdy dog with muscular thighs and a strong jaw. The neck is of medium length, enabling the dog’s head to come down easily to scent (smell the ground). The Beagle has a short, dense coat with the tricolour combination of black, tan and white being the most common coat colouring (Dogs Australia, n.d.).

Working Dogs are grouped together based on their function. Working Dogs are best known for assisting people working with livestock.

37 breeds of Working Dogs are currently listed by Dogs Australia. This group includes sheepdogs, cattle dogs, shepherds and collies, such as the Australian Cattle Dog, Australian Kelpie, Australian Shepherd, Border Collie, and Maremma Sheepdog.

The Maremma Sheepdog was bred to live with livestock and to protect them from predators. As such, it is a large breed, with males standing up to 73 cm at the withers and weighing between 35-45 kg. The Maremma Sheepdog is always all white with a black nose, eyelids and paw pads. To protect them from the elements, the Maremma Sheepdog has a “thick, long, double coat which lies flat to the body with feathering on the tail and the back of the legs. The coat is usually straight but may have a slight wave” (Hennessy, n.d.).

Like the Working Dogs Group, Utility dog breeds were originally created to perform a function in service of people. Typical jobs performed by breeds in the Utility Group included protecting people or property, running alongside carriages, fighting, pulling sleds and search and rescue.

Dogs Australia currently lists 37 breeds in the Utility Group, including, the St Bernard, Siberian Husky, Boxer, Leonberger and Rottweiler.

The Leonberger is a giant breed with powerful and strong males standing 72–80 cm at the withers and females at 65–75cm. With mane-like hair on the chest and neck, the Leonberger almost resembles the lion seen on the town crest of Leonberg, a German town where the breed originated. The Leonberger has a long coat that varies from a “pale cream to a rich red, with a black tipping and mask” (Leonberger Association of NSW, n.d.).

The dogs of the Non Sporting Group were predominantly bred for their appearance, rather than for function. As such, it is the most diverse Group in terms of size, shape and colour.

The Dogs Australia Non Sporting Group currently contains 23 breeds. This Group contains iconic breeds such as the Dalmatian, Poodle (Toy, Miniature and Standard), Sha Pei, British Bulldog and Great Dane.

The Shar Pei is a very squarely built, medium-sized, compact dog with distinctive wrinkles on the head, shoulders and base of the tail. Puppies are often wrinkled all over. The ears are small and triangular, folded over to point towards the eyes, which are deep set. The coat is short, all-over solid colour with some shading around the muzzle and backs of the legs and typically very coarse. The Shar Pei has a wider bottom jaw than the top, and the muzzle, “when viewed from the front, should resemble the shape of a hippopotamus head” (Gooding, n.d.).

Activity: Interpret Breed Standards Documents - Dogs

Go to the Dogs Australia website and locate the Breed Standards for the Saluki. Then, answer the following questions.

- Which breed Group includes the Saluki?

- How tall are male Salukis?

- What colour should the nose be?

- Are Saluki necks described at short and thickset?

- What coat type do Salukis have?

- What is the tail length and carriage?

Q1 Answer: The Saluki is included in the Hounds Group.

Q2 Answer: Saluki dogs are approximately 58-71 cm at the withers.

Q3 Answer: Saluki noses should be black or liver-coloured.

Q4 Answer: No. Saluki necks are long, supple and well-muscled.

Q5 Answer: Hair is soft and silky with feathering on legs.

Q6 Answer: Saluki tails are long with silky feathering on the underside. They are carried low and with a natural curve.

Individual dog identification

When working with multiple dogs of the same breed, you can distinguish between individual animals by examining a few physical characteristics, such as coat colour, markings and sex.

As mentioned previously, coat colour and markings are great ways to identify individual dogs. All coat colours in dogs are caused by just two different pigments:

- Eumelanin (black, which can be diluted to make grey or modified to make brown)

- Phaeomelanin (red, which can be diluted to make orange, cream, yellow or tan).

The different colours are created by combining different amounts of the two pigments. Several genes affect the production of the two pigments, so the individual dog’s specific genetics will determine the amount of the two pigments produced in different parts of its body. For example, switching between producing eumelanin and phaeomelanin in a particular hair follicle will result in agouti (striped) hair, while a lack of both piments creates white hair (Williams & Buzhardt n.d.).

The following list outlines the most common coat colours in dogs:

- Black (predominantly eumelanin produced)

- White (neither eumelanin nor phaeomelanin produced)

- Red (only phaeomelanin produced)

- Blue (diluted eumelanin)

- Brown (diluted and modified eumelanin)

- Cream and tan (diluted phaeomelanin).

Common dog coat patterns include:

- Solid – one colour all over the body.

- Brindle – dark stripes on a light coat

- Piebald – large patches of dark and light hair (the skin pigmentation pattern matches the hair on top)

- Merle – a mottled pattern of dark colour on a diluted background of the same colour

- Blaze – a white stripe down the centre of the face

- Grizzle – a mixture of white hairs with either red or black hairs

- Tricolour – black and tan patches on a white background

- Mask – black muzzle on a paler face, can extend over the eyes

- Sable – diluted colours (for example, silver, gold, brown or fawn) tipped with black (Williams & Buzhardt n.d. and Kawsar n.d.).

Sex and reproductive status can also help distinguish between individual dogs. The genital opening and anus are positioned close together, beneath the tail in females, while male dogs have greater space between the anus and genitals.

There is often no obvious external evidence that a female dog has been spayed (desexed) or is intact (able to breed). Surgical scars may not be visible under the fur. However, most veterinarians will give the dog a tattoo to indicate that they have been desexed. The tattoo, a blue circle with a straight line through it, is placed inside the left ear. However, this tattooing has not been a standard requirement in all states of Australia until recently. So, you will find many older companion animals will not have this tattoo as evidence of desexing.

Intact male dogs will have visible testicles between the anus and penis. A neutered (desexed) dog will not have obvious testicles. However, some males, particularly young puppies, may have undescended testes, which means the testicles are still in the abdomen. In these instances, a physical examination by a veterinarian will determine whether the dog is intact or neutered.

Common cat breeds

The International Cat Association (TICA), the world’s largest genetic registry of pedigree cats, currently recognises 73 breeds of cats (TICA, 2018). The Australian Cat Federation (ACF), on the other hand, only recognises 51 breeds, although some breeds include short and long-hair varieties (ACF, n.d.). However, as with dogs, new breeds are still being developed and may become officially recognised in the future.

The ACF Breed Standards webpage lists all 51 recognised breeds and includes hyperlinks to specific information about the physical characteristics of each breed. The breed standards information includes descriptions of the:

- Head – general shape in profile and when viewed from above.

- Ears – size in proportion to the head, shape and position on the head.

- Eyes – colours, shape and relative position on the face.

- Body – overall shape and general bone density.

- Legs and feet – length of legs, size and shape of paws.

- Tail – length in proportion to the body, thickness and tip shape.

- Coat – hair length, consistency, curl, colour and patterns.

For example, the Ragdoll (shown in the following image) is one of the more common breeds in Australia. This cat is characterised as “a long-bodied sturdy cat with a semi-long silky coat and blue eyes. The Ragdoll has a sweet and docile disposition and has a tendency to become limp (ragdoll-like) when picked up” (ACF 2018, Ragdoll p. 1).

Other common breeds seen in Australia include the Persian, Siamese, Burmese, Russian Blue, Australian Mist, British Shorthair and the Domestic Shorthair (the most common mixed breed cat).

Cat coats

A cat’s coat is one of the main ways of distinguishing between different breeds because the overall size and shape of different cat breeds are so similar. Coat length, colour and pattern are ways to differentiate the breeds.

There are four coat lengths in cats:

- Hairless cats are characterized by their lack of fur (as shown in the following image)

- Shorthair cats have and even coat of short fur that covers their entire body

- Medium hair cats have longer fur around their mane, tail, and/or rear

- Longhair cats have luxurious, fluffy fur all over their bodies.

Black is a common coat colour in cats. Grey is a diluted version of black and is frequently seen under tabby stripes. Pure white cats exist, but white is more commonly seen in a bicolour pattern where patches of white are interspersed with patches of one other colour. Orange, or red, is another common colour, with most orange cats being male. Buff, or tan, is a diluted orange, often accompanied by dark orange tabby stripes. Brown is a less common solid colour and is also usually seen with tabby stripes. Tortoiseshell (tortie) cats have a blend of orange and black patches, while calico cats have distinct patches of solid orange, black and white. Both tortoiseshell and calico cats are predominantly female (Alley Cat Allies, n.d.).

Few cat breeds have a coat of a single colour—instead, different colour blend to form distinct pattern types. There are four main types of coat patterns. Bicolour cats, also known as piebald, have a combination of white fur and one other colour, with varying amounts of white. Pointed cats have light-coloured bodies and darker ears, faces, tails and legs. Shaded cats, most commonly seen in longhair breeds, have fur that is white at the base and gradually darkens towards the tips. Tabby cats have an M-shaped pattern on their forehead and different types of striping. The four main tabby stripe patterns are:

- Classic tabby: wide stripes in a circular, marbled pattern

- Mackerel tabby: thin vertical stripes with a dark stripe along the back (as shown in the following image)

- Ticked tabby: no distinct stripes on the body because individual hairs have bands of different colours, although thin stripes are seen on the face, legs and tail

- Spotted tabby: round spots or circles instead of stripes (Alley Cat Allies, n.d.).

Activity: Interpret Breed Standards Documents - Cats

The Russian breed of cats has three colour varieties – blue is the most common in Australia.

Go to the ACF Breed Standards webpage and locate information regarding the Russian breed. Then, answer the following questions.

- What coloured eyes do Russian Blue cats have?

- What size and shape are the ears of a Russian Blue?

- Are Russian Blues short or long-haired?

- What is special about the Russian Blue coat that makes it so soft and velvety?

- What coloured nose and paw pads should a Russian Blue have?

- What are the two other colour varieties of the Russian breed?

Q1 Answer: The eyes are green.

Q2 Answer: The ears are large and pointed with a wide base.

Q3 Answer: Russian Blues are short-haired cats.

Q4 Answer: All Russian cats have a double coat. The outer coat is thick and very fine, and the undercoat is plush.

Q5 Answer: Nose and paw pads should be blue-grey.

Q6 Answer: Black and White.

Individual cat identification

When trying to identify an individual cat, you will need to look for more specific physical features that make that individual stand out from others of the same breed.

The presence, shape, size and colour of coat markings can be helpful in identifying an individual cat. Common markings include:

- Blaze – a white stripe between the eyes.

- Eye patch – a coloured spot across one eye, typically seen on a mostly white face.

- Locket – a triangular-shaped patch of white on the chest.

- Snowshoe – a pointed overall coat pattern with blue eyes and white markings on the face and body.

- Socks – when one or more paws are a different colour (usually white) to the rest of the coat. Socks can extend up the legs.

- Tail tip – when the tip of the tail is a different colour (usually white) to the rest of the coat.

- Tuxedo – an overall coat pattern that is typically black and white, with white paws, belly and chest and black head, back, legs and tail. Some may also include a white blaze up the nose.

- Van – an overall white coat with coloured patches only seen on the head and tail (Alley Cat Allies, n.d.).

One individual cat can have multiple specific markings.

Other physical features that can help you identify an individual cat include:

- Eye colour, including heterochromia – one eye containing more than one colour, or two eyes of different colours

- Whisker colours

- Nose and paw pad colours

- Damage, scars and injuries, including missing ear tips, kinks in the tail or ear notches

- Sex.

The easiest way to determine the sex of a cat is to examine the distance between the anus and the genital opening. In the case of females, this distance is typically less than 1.5 cm. If a female cat has been spayed, there may be a surgical scar on her abdomen. However, this type of scar is often difficult to see without the assistance of a veterinarian.

The space between the anus and genital opening in neutered males is typically more than 2.5 cm. Although neutered cats no longer have testicles, some cats may still retain additional skin and fur in that area. Intact males also have a distance greater than 2.5 cm between the anus and the genital opening. However, they still have testicles and often have noticeably broader heads and jawlines (Alley Cat Allies, n.d.).

Activity: Identify the breed

From the following lists, identify the breed of each of the dogs that are shown in the provided photographs. Refer to the Dogs Australia breed standards, if necessary.

| Dog 1 | Dog 2 | Dog 3 |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

| Possible breeds | ||

|

|

|

- Standard Poodle

- Australian Cattle Dog

- Miniature Schnauzer

From the following list, identify the breed of each of the cats that are shown in the provided photographs. Refer to ACF breed standards, if necessary.

| Cat 1 | Cat 2 | Cat 3 |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

| Possible breeds | ||

|

|

|

- Sphynx

- American Shorthair

- Burmese

Common companion birds

There are thousands of bird species, which vary dramatically in size and colour. When identifying a species of bird, the key physical characteristics to consider include the following:

- Body size

- Beak shape, size and colour

- Feather colours and patterns

- Foot structure

- Tail shape and length relative to body size.

Bird species within the same taxonomic family tend to be more similar in appearance to each other than to species from a different family. For example, select the following headings to learn more about four families of Australian birds.

Family: Estrildidae

Number of species in Australia: 20

General description: Small birds, 10-16.5 cm in length and only weighing between 9.5 and 20 g. All species have strong, thick, wedged-shaped beaks for cracking open seeds. The break is bright red in most species. All Australian grass finches are anisodactyl, with three toes facing forwards and one facing backwards. Each species has its own distinctive colours, markings and tail shape and length.

Common behaviour: Australian grass finches are social birds and often gather in small flocks. They also form strong pair bonds with the males performing courtship ‘dances’ for the females (Bird Australia 2009).

Example species: Zebra Finch, Diamond Firetail, Gouldian Finch, Star Finch and Crimson Finch (shown in the following image).

Family: Corvidae

Number of species in Australia: 5

General description: Large perching birds between 45 and 54 cm long. All Australian species are an all over glossy black and have white eyes and are anisodactyl. Where ranges overlap, it is often easier to distinguish the similar-looking species by size and calls.

Common behaviour: As very intelligent birds, ravens and crows eat a variety of different plant and animal foods, often the first species to make use of a new food source. Some species are known to use tools to access difficult foods (Bird Australia 2009).

Australian species: Australian Raven (shown in the following image), Forest Raven, Little Raven, Little Crow and Torresian Crow.

Family: Petroicidae

Number of species in Australia: 22

General description: Small perching birds between 11 and 18 cm long. Most species eat insects, using a perch-and-pounce method to catch them and so they all have very similar shaped beaks. However, Australasian Robins vary in colour. All species are anisodactyl.

Common behaviour: Most species build small, cup-shaped nests from bark and cobwebs and “have high-pitched, short, and staccato songs, or give drawn-out whistles or trills” (Bird Australia 2009).

Examples of Australian species: Scarlet Robin, Flame Robin (shown in the following image), Eastern Yellow Robin, Mangrove Robin and Rose Robin.

Families: Cacatuidae (Cockatoos) and Psittaculidae (Australasian true parrots)

Number of species in Australia: 53

General description: Vary dramatically in size from 14-60 cm in length. However, all species share many physical characteristics, including plump bodies with a short neck, strong curved beaks with a bare patch of skin at the base, four fleshy toes in a zygodactyl arrangement (two toes pointing forwards and two pointing backwards). Body colours and patterns and tail length and shape vary dramatically between different species although bright and contrasting colour are common. All cockatoo species have crest feathers on the top of their head, which they can raise or flatter. True parrots do not have crests.

Common behaviour: Parrots are very social, even with humans. They are rarely seen on their own, and some species, such as the Budgerigar, can form super flocks with thousands of individuals. They are very intelligent and will playfully interact with each other and objects. They don’t sing but they do vocalise, and many have the ability to mimic human speech. Most species lay their eggs in tree hollows without any nesting material (Bird Australia 2009).

Examples of Australian cockatoo species: Cockatiel, Red-tailed Black Cockatoo, Sulphur-crested Cockatoo, Galah and Palm Cockatoo.

Examples of Australian true parrot species: Eastern Rosella, Eclectus Parrot, Orange-Bellied Parrot, Rainbow Lorikeet and Budgerigar. Review the following video, Biggest Swarm of Budgies (2:13), for an excellent overview of Budgerigar behaviour.

Many people in Australia keep companion birds. Parrots are common companion birds due to their intelligence and their ability to form bonds with humans. Some of the most common companion parrots in Australian homes include the Budgerigar, Cockatiel (as pictured in the following image), Rainbow Lorikeets, Scaly Breasted Lorikeets, Indian Ringneck and Eclectus Parrots.

Common pet reptiles

Reptiles are a class of animals that includes snakes, lizards, crocodiles and turtles. Reptiles are excellent pets for those who may be allergic to animal hair, or who prefer quiet, relatively low-maintenance pets. Some of the most common companion reptiles in Australia include the Centralian Carpet Python, Children's Python, Eastern Long-necked Turtle and Central Bearded Dragon.

Permits for keeping pet reptiles

In Australia, it is illegal to own a non-native reptile, and you require a permit or a licence to own many species. The different States and Territories have different rules and regulations around which species require a permit. The following table outlines the regulations across Australia (Petbarn 2022).

| State or Territory | Overview | Links |

|---|---|---|

| Australian Capital Territory | It is illegal to remove reptiles from the wild. Not all species require a permit. | What animals can be kept in the ACT? |

| New South Wales | It is illegal to remove or return a reptile to the wild. Pets must be purchased from a licensed dealer. | Reptile keeper licences |

| Northern Territory | Most reptile species require a permit to be kept as a pet. | Native animals that need a permit |

| Queensland | There are specific conditions to restrict owners from breeding and/or selling or giving away reptiles. | Recreational wildlife licence |

| South Australia | Permits are required to keep reptiles to prevent them from being illegally removed from the wild. | Keep, sell or display native animals (including eggs) |

| Tasmania | Department of Natural Resources and Environment Tasmania discourages keeping reptiles as pets. However, reptiles can be kept with a permit. | Herpetofauna Permits |

| Victoria | There are four different license types depending on the type of wildlife, including reptiles, to be kept. | Private wildlife licences |

| Western Australia | Not all species require a permit. | Licences and Authorities: Fauna licences |

Identifying types of reptiles

All reptiles have dry, scaly skin and are cold-blooded. There are well over 800 species found in Australia, so you are not expected to be able to identify all of them. Some species are very difficult to tell apart. However, there are some key physical features that will help you distinguish between the main types of reptiles.

Crocodiles are large, predatory reptiles, with the Saltwater Crocodile (an Australian native) listed as the largest living reptile species (up to 6 m long and weighing over 1000 kg). Crocodiles are characterised by their unique body structure, which allows their eyes, ears, and nostrils to remain above the water surface while most of their body remains hidden below. They have powerful jaws with numerous conical teeth and short legs with clawed webbed toes. Their long and massive tails, coupled with their thick, bony-plated skin, contribute to their distinctive appearance.

The following skull and head features are used to identify species of crocodile:

- proportions of the snout

- shape and number of bony structures on the upper surface of the snout

- number and arrangement of scales on the head (Wermuth & Ross, 2023).

Turtles are characterised by the presence of a hard, bony shell that is a part of their skeleton. Depending on their habitat type, they may have flippers or feet. The following physical features are typically used to identify turtle species:

- whether the limbs are flippers (sea turtles) or feet (tortoises and freshwater turtles)

- whether the animal walks on its toes (tortoise) or on the flats of the feet (freshwater turtle)

- the shape and size of the plastron (the underside of the shell)

- the number, shape and patterns on the scutes (the scales on the shell)

- length of neck and patterns (Akoto 2023).

Snakes are legless reptiles. They have a forked tongue, no visible earholes and no eyelids. The elapids are the largest family of snakes in Australia and include all the venomous snakes with fangs at the front of the jaw, such as the Inland Taipan and Tiger Snake (pictured in the following image).

While the size, length and patterns of the different species vary, all elapids have the following physical features that distinguish them from other Australian snakes:

- missing loreal scales (the scale between the nose scales and the scales directly in front of the eyes)

- most species have a single row of subcaudal scales (the underside of the tail)

- a cylindrical, tapering tail that ends at a point

- a head that is typically not much wider than the neck

- hollow fangs, capable of injecting venom into prey

- round pupils

- additional teeth are smaller and often hollow as well (Shea, Shine & Covacevich 1993, pp. 10-14).

Boidae is another distinctive family of snakes in Australia, which includes all Australian pythons, such as the Centralian Carpet Python (pictured in the following image) and the Stimpson Python. Australian pythons are non-venomous and kill their prey by constriction (squeezing).

Australian pythons have the following physical features that distinguish them from Australian elapids:

- vestigial pelvis (only seen via x-ray) and many species have cloacal spurs (tiny protuberances that are remnants of hind legs)

- vertically elliptical pupils

- a large mouth, which makes the head triangular and distinctly wider than the neck

- numerous solid, pointed teeth instead of hollow fangs

- most species have heat-sensing pits along their lower jawline

- most species have paired subcaudal scales (Ehmann H 1993, pp. 4-6).

When identifying the species of a snake, the following diagnostic features of typically used:

- overall length

- body shape, including thickness and length of the tail (the tail starts just behind the cloaca) relative to the body

- shape of the head and neck

- colours and patterns

- number, shape and arrangement of scales on the head

- subcaudal scale arrangement

- scale texture

- pupil shape.

Most people would think that lizards can be easily distinguished from snakes by the presence of legs. However, not all lizards have obvious legs! Some key differences between snakes and lizards are that most species of lizard no not have a forked tongue, while all snakes do; snakes do not have visible ears, while all lizards have visible ear holes; no species of snake have eyelids, while many species of lizard do.

There are five families of lizards found in Australia:

- Gekkonidae: Geckos have characteristically large eyes with a narrow vertical pupil, but no eyelids. Instead, the eyes are covered by a transparent brille (a scale to protect the eye). Geckos have loose-fitting velvety skin with very small scales on the top surface (King & Horner 1993, p. 6).

- Pygopodidae: Legless lizard species are all long and slim and look like a snake at first glance. While there is no evidence of front limbs externally, all species have vestigial hind limbs that look like short scaly flaps. They are covered in overlapping scales and have a tail that is often longer than the rest of the body. Like geckos, legless lizards have vertical pupils and a brille instead of eyelids (Shea 1993, p. 4)

- Agamidae: Australian dragons have a single row of sharp canine-shaped pleurodont teeth, which can be lost and replaced throughout the life of the animal. They do not have large scales on their head and body scales are typically rough and irregularly shaped. Australian dragons have relatively loose skin, which forms permanent folds. Most species have an obvious gular fold, which extends from the chin down under the jaw and throat. All species have eyelids and a wide, flat tongue (Witten 1993, p.7-9).

- Varanidae: Australian monitors, also known as Goannas, have several distinctive characteristics that differentiate them from the other families of lizard. They have a deeply-forked tongue; eyelids; loose-fitting skin with tiny scales; a long slender neck and body with a long muscular tail; the feet have five clearly defined toes, each with a strong claw; and they are the only family that do not display tail autonomy – the ability to intentionally drop the tail as a form of predator escape (King & Green 1993, p.4).

- Scincidae: Most species of Australian skinks tend to have long snouts and relatively flattened heads, which are covered by very large scales called head shields. The head is typically small and the same width as the neck, but the tail is long and tapering. The body is quite square, and the strong limbs have well-defined toes (Hutchinson 1993, p. 8-11).

Use the arrows following the slider to see an example of a species from each of the lizard families:

- Image 1: Asian House Gecko. Family: Gekkonidae.

- Image 2: Common Scaly-foot Legless Lizard. Family: Pygopodidae.

- Image 3: Centalian Bearded Dragon. Family: Agamidae.

- Image 4: Perentie. Family: Varanidae.

- Image 5: Common Blue-tongued Skink. Family: Scincidae.

Native wildlife

While a permit or licence is required to keep many species of native wildlife as pets, native species are commonly exhibited animals and often require human assistance during natural disasters, such as bushfires, or after a road incident.

Some of the more common native species that find their way into animal hospitals and wildlife rescue centres include:

- Native birds, such as the Galah, Sulphur-crested Cockatoo, Little Corella, Noisy Minor and the Australian White Ibis

- Native mammals, such as the possums, wombats, kangaroos and wallabies, koalas and echidnas.

Most of the well-known Australian mammals are marsupials – which means they give birth to underdeveloped young and carry them in a pouch until they are more independent. Macropods are a family of marsupials with an obvious pouch (in females), very long hind feet and muscular tails that they use when they bound along. Common macropods include the Easter Grey Kangaroo, Red Kangaroo, Pademelon and Swamp Wallaby.

It is easy to picture the marsupial pouch as a ‘big pocket’ as seen in the macropods. However, in many species, it is little more than a fold of skin over the nipples, where the babies attach. The pouches of koalas and wombats are distinctive, in that they open backwards! Echidnas are monotremes – meaning they lay leathery eggs instead of having a pouch. The other species of monotreme is the Platypus.

There are also native placental mammals in Australia. Placental mammals, including humans, give birth to relatively well-developed young. Native placental mammals include the Dingo, all native bats, such as the Grey-headed Flying Fox, and native rats and mice, such as hopping mice and water rats (or Rakali).

Common forms of visual identification

Depending on the animal care facility in which you work, you may have multiple individual animals of the same species and breed that may be difficult to distinguish. In these situations, and as a method of confirming you have the correct individual animal in any animal care situation, you can check for other common forms of visual identification. These visual indicators should be included on the animal’s record to help with identification.

While it is common for companion animals to have an identification microchip inserted under the skin, you cannot use them as a form of visual identification because you will need a scanner to read the information the microchip carries.

Collars and name tags

Many companion animals wear a collar. Collars can be distinctive in colour or pattern to help distinguish similar individuals from a distance. For example, a small house herd of goats may all have different coloured collars to help the owner identify the individuals. Often integrated with a collar, many companion animals wear a tag with their name written on it. Name tags can also include contact details for the owner.

Brands

Brands are marks made on the skin of an animal using either a hot or a cold brand (a piece of metal in a specific shape used to represent the owner of the animal).

Hot branding uses a heat brand, which burns the hair and leaves a permanent scar on the skin. Freeze branding uses a brand cooled with dry ice or liquid nitrogen, which damages the pigment cells and causes the hair to grow back white, as shown in the following image.

Tattoos

Both companion animals and livestock may have identification tattoos. These are often located on the inside of the ear, inside the lip, on the inner thigh or even on the belly, depending on the animal. Animal tattoos are generally used to indicate whether a companion animal is intact or has been desexed. In livestock, tattoos can be used to record information about the individual, such as birth date, parentage or health history.

Ear notches

An ear notch is a small section of the ear that is removed. The number and location of ear notches can be used to record various information, such as identifying an individual as part of a specific litter or signifying that the animal has been desexed. Ear notching is sometimes used on wild animals to indicate individuals that have been captured and released during ecological research.

Ear tags

Ear tags are still the most common way to identify individual livestock animals, such as cattle, sheep and goats. The coloured and numbered tags are inserted into one or both ears of the animal and help identify the owner as well as the individual animal.

Leg bands

While many companion birds are large enough to carry a microchip, leg bands are a common method of identifying individual birds. A leg band is a small ring with a number printed on it, which wraps around the bird’s ankle. Leg banding is common in wild birds for research purposes and in aviculture as a method of identifying birds for breeding records.

The Australian Bird and Bat Banding Scheme (ABBBS) is an Australian Government project that bands and collects information about migratory bats and birds. Each bat or bird is banded with a unique serial number (typically eight digits in the format, XXX-XXXXX) and a contact address. Migratory birds may have been banded in a different country and then flown to Australia.

The ABBBS encourages people to report any banded bats or birds that are sighted or found injured or dead. If you want to report a banded animal, follow the instructions on the How to report a bird or bat band recovery in Australia webpage.

Leg bands in aviculture (the practice of keeping and breeding captive birds) also identify individual animals. In many cases, only the owner will hold the record of all the leg band numbers. They use the information to record which individuals have bred, when, with whom and the offspring they produced.

Aviculture leg bands may also be recorded with agricultural societies, such as The Avicultural Society of Australia.

Once you have identified the individual animal, you can start to observe, identify and interpret their behaviour. The behaviour will help inform you of the best and safest way for you to approach and interact with that animal.

The distance assessment

The process of observing an animal before you approach it is called a distance assessment. You should do this before interacting with any animal, no matter how familiar you are with a particular individual and regardless of the type of interaction you are planning.

During your distance assessment, you can evaluate aspects of the animal’s physical and emotional states by observing the animal and its behaviour.

It is also helpful to obtain information about the individual animal before you approach and handle it. You can combine this information with your conclusions from your distance assessment and use these insights to help you choose appropriate PPE, equipment and low stress handling techniques for that animal.

Obtain information about the individual animal

There are several sources that you can access to obtain information about an individual animal, including:

- breed standards

- individual animal records

- the owner or regular handler.

Obtaining behavioural information from breed standards

Breed standards for cats, dogs and horses often include details about the typical temperament of the breed. The temperament of an animal is the overall, general behaviours and emotional states expected from that breed or individual.

For example, Dogs Australia (2017) describes the temperament of the Pekingese as “fearless, loyal, aloof, not timid or aggressive”. In contrast, the Dobermann temperament is described as typically bold and alert. Although shyness or viciousness are not uncommon, these temperaments are undesirable (Dogs Australia, 2009).

General temperament is one factor that helps to classify dog breeds into a particular Group. However, it is important to remember that breed standards are a generalisation only. You should always consider the animal in front of you, rather than assume it meets the expectations of the breed standard.

Obtaining behavioural information from animal records

Animal records are formal sources of information about individual animals and are kept at the workplace. Depending on your specific workplace, animal records make take the form of:

- Cage cards

- Individual animal records

- Client histories

- Veterinary Behaviouralist reports

- Animal Trainer reports

- Ranger reports.

Animal records should be kept up to date and will likely include information about the animal’s current physical condition, emotional state and behaviour. Make sure to read animal records carefully to interpret the information accurately. If the information is outdated or inaccurate, and it is appropriate for your role to do so, update the record using industry terminology.

Obtaining behavioural information from the owner

The owner or regular handler of the animal will know the animal and its typical behaviours and emotional states the best. These people are an excellent source of information about the animal and its needs. Remember, though, that any animal may behave differently when in a different environment or in the care of a less familiar person.

To obtain information from talking to a person, make sure to use active listening and questioning skills.

Active listening and questioning skills

You can also obtain information about an individual animal by talking to other people, such as the owner or regular handler of that animal.

Active listening means giving someone your full concentration and paying attention to more than just the words they say. In other words, an active listener takes in non-verbal cues, such as body language and tone of voice, as well as the verbal message.

Active listeners use verbal and non-verbal signs to indicate they are listening actively. In the article, ‘What Is Active Listening?’, Cuncic (2022) suggests the following seven key active listening techniques:

- Be fully present. Don’t be distracted by other people or your surroundings. Put down your phone and focus only on the speaker.

- Pay attention to non-verbal cues. Consider the speaker’s tone of voice and speed of speech. Is their body language open or closed? Consider your own non-verbal cues. Don’t cross your arms or fidget, instead, show that you are listening by facing your body towards the speaker, smiling and nodding when you age or understand what they are saying.

- Keep good eye contact. Maintain eye contact for 50-70% of the conversation but only hold contact for four to five seconds at a time. Any longer starts to feel a bit awkward.

- Ask open-ended questions. Open-ended questions required detailed answers and show that you are paying attention. They can help you get the specific information that you need.

- Reflect what you hear. Summarise or paraphrase what the other person said and repeat it back to them. This gives them a chance to clarify or correct you if you have misinterpreted anything.

- Be patient. Don’t interrupt, finish the speaker’s sentences or change subjects abruptly.

- Withhold judgement. Remain neutral and avoid judgemental responses or reactions.

Open-ended and closed-ended questions

Asking questions is a fantastic way to find out information. Questions can be classified into two broad types:

- Open-ended questions

- Closed-ended questions.

Open-ended questions typically begin with words or phrases such as “what”, “where”, “when”, “why” and “how”. They require detailed responses and are a great way of finding out new information.

Closed-ended questions can only be answered by a very narrow range of possible answers. Typical closed-ended questions can be answered with a simple ‘yes’ or ‘no’ or a small piece of specific information. Close-ended questions are great for clarifying information or confirming that you have correctly understood an instruction.

Funnelling

A good technique to use when seeking information or advice is to use funnelling to question, clarify and confirm. Start with broad, open-ended questions to gain the information you need. Then, use close-ended questions to learn specific details, clarify your understanding and confirm the information you have received.

Assessing physical condition

An accurate assessment of an animal’s physical condition will provide important health information that should influence how you approach and handle that animal. For example, an animal with an injury will need to be handled with care, an overweight animal will likely be uncomfortable if you pick them up around their middle, and an animal with a very high respiration rate may be stressed and should be approached with caution.

The aspects of an animal’s physical condition that you can gauge during a distance assessment include the following:

- Body condition

- Coat condition

- Respiratory rate

- Visible signs of illness or injury.

When conducting any type of assessment of an animal, physical or behavioural, it is vital that you know what is ‘normal’ for that species or breed. For example, 85 breaths per minute might be normal for a pet rat but would be extremely concerning for a dog at rest.

Body condition

During your distance assessment, you can conduct an initial evaluation of body condition - the body fat level of an animal, relative to its size. A body condition score (BCS) provides an indication of the overall health of the animal in terms of nutritional status and healthy body weight.

The scale of BCS is often presented visually, such as in the Guinea Pig Body Scoring Condition Chart (2022) from Oxbow Animal Health. If you are required to determine the BCS of an animal, you will also need to put your hands on them, which you can do after the distance assessment. Ensure you follow your workplace procedures for assessing BCS and use the correct scale for the species and your workplace.

Coat condition

Evaluate the level to which the coat looks clean and groomed, whether there is any matting or missing hair and whether there are any obvious signs of skin irritation. If you see coat or skin issues, try to avoid touching those areas to prevent discomfort for the animal. Coat condition can also indicate a health issue that may be infectious and zoonotic, such as ringworm. Your observations of coat condition, or any other aspects of physical condition, should inform your decision about what PPE is required when interacting with that animal.

Respiratory rate

Respiration rate (RR) is the number of breaths an animal takes in a minute. To check the animal’s RR, watch the chest rise and fall or listen closely to the animal’s breathing. Count the number of breaths for a period of 15 seconds and multiply this number by 4.

You can also assess the quality of the animal’s breathing at the same time, such as whether the breathing is laboured or if you can hear wheezing or coughing. Unusual RR or breathing quality may indicate an illness or injury, so it is important that you know what ‘normal’ RR and breathing should look and sound like for that species or breed.

Illness or injury

Look for visible signs of illness or injury, including evidence of vomiting or unusual evacuation (diarrhoea), bleeding or broken bones. Judge whether the animal’s posture – the way it holds itself when standing or sitting – or gait – the way it moves when walking – is normal for that species and breed. An unusual posture or gait may be another indication of illness or injury.

Animals of advanced age may also display altered postures or gaits due to arthritis or other ailments that are common to senior animals. Animals with hearing or sight loss will require sensitive handling so as not to frighten the animal with unexpected contact.

Assessing behaviour

Animals can’t talk. So, you must rely on your assessment and interpretation of their behaviour to identify the likely reasons for their behaviours and to determine the best and safest way to interact with that animal.

Aspects of an animal’s behaviour you should consider during your distance assessment include:

- demeanour

- body language

- vocalisations

- coping behaviours.

Demeanour

Demeanour is the general alertness and responsiveness of an animal. An animal’s demeanour typically indicates its emotional state or the seriousness of an injury or illness.

During your distance assessment, observe the animal’s behaviour and note its demeanour. The following are some terms that are commonly used to indicate the demeanour:

- BAR - Bright, alert and responsive

- QAR - Quiet, alert and responsive

- Altered mentation – confusion or change in typical responses for that animal

- Depressed or dull – slow or reluctant to respond

- Obtunded – lethargic or sleepy

- Stuporous – unconscious or very difficult to rouse

- Comatose – unconscious and completely unresponsive.

If you work in animal health, you may be required to conduct a more specific and detailed assessment of animal demeanour and apply terms that are not provided here.

Body language

The body language and movement of an animal will tell you a lot about its likely emotional state and arousal level. Body language is the way an animal holds and moves parts of its body. The posture (body positioning) of an animal may give you clues to its physical wellbeing as well as its emotional state. For example, a dog limping or holding its paw up may indicate an injury to the leg, or cat tucking its tail in close to its body is a typical indicator that the animal is starting to become anxious or fearful.

Large movements of the entire body or whole limbs are considered gross movements. Gross movements are typically obvious and easy to observe. An example of gross movement is avoidance, where the animal turns its whole head away or physically gets up and moves away from you.

When assessing the gross movements of an animal, consider the posture and motion of the:

- head

- body core

- limbs

- tail.

Fine movements are either very small or only affect very specific parts of the body. Fine movements include changes in the posture, position or movement that may be very subtle, such as a change in the tension of the muscles in an area of the body. When assessing the fine movements of an animal, carefully watch for changes in the posture, tension and motion of the:

- eyes, including pupil dilation and the amount of whites shown

- mouth, including the tongue, lips and number of teeth shown

- ears, tension and posture

- brow, tension and furrowing

- whiskers, tension and position

- coat, including shivering, shaking and piloerection (raised hair).

Vocalisations

While animals can produce sounds in a variety of ways, vocalisation is the process of producing a sound from the larynx (voice box). Common animal vocalisations include:

- dogs barking, growling, howling or whining

- cats meowing, growling, hissing or purring

- horses whinnying, snorting, nickering and squealing

- rats grunting, chirping or screaming.

The frequency, volume and type of vocalisation can indicate a range of emotional states that an animal experiences. The absence of vocalisation can also be very telling. For example, a normally ‘chatty’ cat that is suddenly very quiet, might indicate a problem with its wellbeing.

Coping behaviours

Coping behaviours, often called calming signs, are behaviours that animals do to signal that they find another animal or person to be too aggressive or a situation to be stressful or frightening. Coping behaviours are ways an animal copes with a stressful situation. They communicate that they are getting stressed, anxious or fearful and ‘politely ask’ the other individual to calm down.

It is very easy for a person to misinterpret calming signs. For example, a dog that turns its head away from the owner and yawns while the owner is telling them off is not showing signs of being bored or disinterested. Instead, the dog is more likely trying to present a calming sign to the owner to say, “You’re very angry, and it’s frightening me. Please calm down a little.”

The cure for [coping behaviours] is to determine the source of the stress and to remove it, if possible.Cats International, n.d.

In general, coping behaviours are typically displacement behaviours – that is, they are normal behaviours displayed at abnormal times or in unusual situations. Animals display displacement behaviours when they are experiencing strong and conflicting motivations, which results in uncertainty. For example, “a harassed cat may be undecided about whether to run from its attacker or to stand and fight. Instead, the cat displays a third, unrelated behavior, such as grooming” (Cats International n.d.).

All animals display coping behaviours. In most species, common coping behaviours involve grooming or pretending to feed in the middle of a stressful situation.

Dog coping behaviours

Turid Rugaas, an internationally renowned dog trainer, helps owners to recognise and respect the 30+ calming signs that dogs display. When these behaviours are ignored or misinterpreted, it can lead to significant behavioural and emotional issues in the dog (Rugaas 2013).

The following list provides a number of examples of dog coping behaviours:

- yawning

- turning the head away while not moving the body

- turning the whole body away

- a quick lick of the nose and/or lips

- dropping into a play bow and holing still for a few seconds

- sniffing the ground when there doesn’t appear to be anything to sniff

- slow walking and/or walking in a curve rather than in a straight line

- scratching when there is no itch

- excessive grooming or licking of a paw or other body part

- whole-body shake when not wet

- panting even though there was no exercise

- freezing, sitting or lifting one paw when meeting a person or other dog.

Coping behaviours are typically displayed when the dog perceives a potential threat, such as:

- another dog or a person approaches directly from in front of the dog

- another dog or a person approaches very quickly

- a person bends or reaches over the top of the dog

- the dog is taken by surprise

- another dog or person is staring directly at the dog.

Review the following video, Beacon's Body Language Breakdowns Episode 01 (2:53 min), to see what happens when coping behaviours and calming signs are not identified or correctly interpreted.

In the following video, Beacon's Body Language Breakdowns Episode 02 (1:47 min), the coping behaviours and signs behaviours are correctly interpreted and respected.

Cat coping behaviours

Grooming is one of the most common cat coping behaviours. Most cats will briefly groom their sides or back after they have been upset. However, if the grooming becomes compulsive or excessive, it is known as psychogenic alopecia. Cats suffering from psychogenic alopecia often remove large patches of fur, typically on the lower abdomen and lower back region, as well as the legs and feet.

Other severe cat coping behaviours include compulsive sucking and chewing of materials and pica – a compulsion to eat inappropriate non-food items (Cats International n.d.).

Less harmful coping behaviours include:

- head flicking

- rapid and/or repetitive licking

- chasing or pouncing on imaginary prey

- vocalising

- yawning

- kneading with paws

- self-spacing or taking a time out

- seeking comfort from the owner

- purring.

Horse coping behaviours

Horse, like cats and dogs and most other species, have a range of coping behaviours that they display when they are stressed or want to de-escalate a situation. Horse coping and displacement behaviours include:

- standing with eyes half closed

- blinking

- licking and chewing with an empty mouth

- yawning

- lowering the head to sniff the ground or to snatch grass

- turning the head away from the stimulus

- rubbing nose and face on the knee (Pet Professional Guild Australia 2018).

Anthropomorphism

Anthropomorphism is the tendency to attribute human characteristics, emotions and intentions to animals. It happens because we try to understand and relate to the world around us based on our own experiences as humans. While it might seem natural to assume animals think and feel like we do, anthropomorphising animals can be risky when interpreting their behaviour.

Projecting human emotions onto animals can lead to:

- misunderstanding the animals’ true motivations and needs

- unrealistic expectations and incorrect predictions of the animals’ responses and behaviours

- ineffective strategies for their care and training.

For example, a dog baring its teeth is probably not ‘smiling’ but displaying warning behaviours before becoming aggressive.

Nonetheless, animals do experience a range of emotional states. It is just important to interpret the situation from the animal’s perspective rather than from a human’s point of view.

Consider a Tiger Snake raising the first quarter of its length off the ground and doing mock strikes. Most people would likely interpret this as aggressive behaviour. However, that interpretation of behaviour is from the human perspective. From the snake’s perspective, a bushwalker is a threat. Humans are too large for any Australian snake to eat, so they don’t want to bite you if they can avoid it. Any lunge or strike is a warning or defensive behaviour against what the snake perceives as a large animal about to hurt them (Pree 2010).

Interpreting animal behaviour

Once you have observed an animal’s behaviour, you then need to interpret it correctly, without anthropomorphising. The three things you want to determine about the animal are its:

- emotional state

- arousal level

- most likely motivations for the behaviours you have observed.

The correct interpretation of these things will enable you to choose appropriate low stress handling techniques based on observation of the animal's behaviour.

Emotional states

While it is unlikely that animals experience emotions in the same ways as humans, they do exhibit clear emotional states. However, there is no industry-agreed number of emotional states experienced by animals.

Jaak Panksepp, a professor of integrative psychology and neuroscience at Washington State University, describes seven general emotional states in animals and categorises them as either positive or negative states:

- Seeking

- Lust

- Care

- Play

- Rage / Anger

- Fear

- Panic / Sadness (Ramanujan 2016).

Seeking, lust, care and play are classified as positive emotional states because they result in the increased release of serotonin and dopamine, neurotransmitters in the brain that typically cause positive feelings. Rage, fear and panic are negative emotional states, which prevent the release of the ‘happy’ neurotransmitters in the brain.

Neutral emotional states are those where the amounts of serotonin and dopamine are at ‘normal’ levels. Neutral emotional states are primarily when the animal is calm but alert or asleep.

The different emotional states are important for the survival of a species. They provide the drive for individuals to display behaviours that increase the likelihood of survival and reproduction.

Seeking

Seeking is a positive emotional state associated with curiosity and active enthusiasm for finding resources. The seeking emotional state is general-purpose. However, it is an essential state that enables mammals to acquire resources from the environment that are needed for survival and reproduction. Essential resources include food, water, shelter and social interaction.

Many enrichment toys and activities promote the seeking emotional state by motivating the animal to find food rewards.

Lust

Lust is a positive emotional state associated with courting and mating behaviours. Lust is closely linked to the seeking emotional state – seeking mates and resources needed to attract a mate. The emotional state of lust promotes sexual desire and promotes sexual engagement, thereby ensuring the breeding and propagation of the species.

Care

Care is a positive emotional state associated with nursing, grooming and protecting offspring and other individuals. As with lust, care is very much part of the seeking emotional state – seeking social interaction and resources to provide to offspring. Arousal of this emotional state also helps to establish and maintain positive relationships between adult breeding pairs. In other words, the emotional state of care helps to nurture the bonds between individuals that mate for life, outside the breeding season.

Play

Play is a positive emotional state associated with the behaviours of social engagement. As with the other positive emotional states, play is closely related to the seeking emotional state – the drive to seek out social interactions. Particularly vital to young animals, social play is very important to the continuation and evolution of species. Play promotes social competence in adulthood.

Rage

Rage (or anger) is a negative emotional state associated with aggression towards an individual that wants to take resources away from you. The emotional state of rage helps animals defend their own life as well as any resources that are of value to them. Rage can be activated as a result of frustration – such as during territorial conflicts. It is important to note that the emotional state of rage can be triggered by a perceived threat. The threat does not need to be real. For example, a silverback gorilla may respond aggressively to its own reflection.

Fear

Fear is a negative emotional state associated with feeling concerned for your own safety and wellbeing. The activation of the emotional state of fear is in response to a perceived danger and triggers behaviours that enable the animal to escape the potentially life-threatening situation.

Panic

Panic (or sadness) is a negative emotional state associated with feelings of separation distress and loneliness. In prolonged or extreme cases, it can lead to depression. Panic can be triggered, for example, by the loss of your caregiver (Kurland 2014). From an evolutionary perspective, the emotional state of panic ensures the survival of a species by motivating animals to seek social interactions and caregivers. The presence of caregivers or other individuals generally increase the chances of survival, compared to an individual animal on its own. Social species share resources and offer greater protection from predators.

Arousal

Related to alertness, arousal is a physiological state of readiness for action. When the brain is stimulated by sensory stimuli – sights, sounds, smells, tastes and contact – it triggers the release of two hormones from the adrenal glands:

- adrenaline

- cortisol.

Sometimes called stress hormones, adrenaline and cortisol work together to produce the fight-or-flight response. For example, reacting to a perceived threat by either confronting the threat (fight) or running away (flight). However, adrenaline and cortisol are also released when an animal is excited, such as in playing with another dog or a toy! Adrenaline and cortisol prepare the body for activity by increasing heart rate, respiratory rate, and blood pressure, and providing the muscles with extra nutrients in preparation for action.

The higher the levels of adrenaline and cortisol in the bloodstream, the higher level of arousal in the animal.

This relationship between arousal level, or stress level, and behaviour is known as the Yerkes-Dodson law. The Yerkes-Dodson law states that there is a “relationship between stress and performance and that there is an optimal level of stress corresponding to an optimal level of performance” (Nickerson 2023).

In other words, when the arousal level is low, the animal is not engaged or interested in what is happening. However, if the arousal level is too high, the animal is too stressed or overexcited to interact effectively or predictably perform desired behaviours. Engagement, responsiveness and behaviour are “best when arousal levels are in the middle range” (Nickerson 2023).

Levels of arousal

The arousal level of an animal is often generalised into the following broad categories, as indicated in the previous figure:

- Blue: Very low or well below threshold - the animal is completely disengaged or asleep.

- Green: Low or below threshold – the animal is calm but alert and responsive to direction.

- Green: Optimal arousal – up to the arousal threshold where the animal is alert, responsive and in control of their emotional state.

- Green: At threshold – the animal is engaged and responsive but at risk of becoming overstimulated.

- Yellow: Over-threshold – the animal is starting to become overstimulated and is less responsive to direction.

- Red: Hyper-aroused or well over-threshold – the animal is overstimulated, behaving unpredictably and is unable to control their emotional state or behaviours.

Threshold is the level of arousal at which the animal starts to lose self-control and behaves inconsistently and unpredictably. Regardless of the emotional state the animal may be experiencing, animals that are over-threshold are less receptive to positive interactions with and directions from people, and the risks associated with handling them are much higher than with an animal of a lower arousal level.

A traffic light system is often used to indicate both the animal’s responsiveness to direction and the risk level associated with working with the animal at the different levels of arousal.

The best course of action when working with a hyper-arousal animal is to try to help it to lower its arousal level before attempting to handle or interact with it. To reduce arousal, if it is safe to do so, you need to remove the stimulus that is causing arousal to increase. If you are unable to remove the stimulus, or if that is not enough, you may simply need to walk away and let the animal calm down and try again later.

For example, consider two puppies playing together – the emotional state of play. The arousal level in both puppies increases from at threshold (green) to over-threshold (yellow), and they both quickly become hyper-aroused (red). Their play becomes overly rough, starts to be aggressive, and the puppies are at risk of hurting themselves or each other. The puppies should be separated and removed from the situation (remove the stimulus) and allowed time for their heart rate and respiratory rate to reduce and return to normal as an indication of arousal level returning to below threshold. If it is safe to do so, the puppies can start to interact again.

Arousal and emotional state

Arousal and emotional state are also interrelated. For example, an animal in a positive emotional state but hyper-aroused will behave unpredictably (such as the puppies from the previous example), even though they are not in a negative emotional state.

Recognise common behaviours