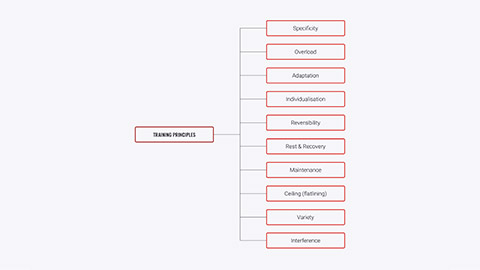

In this topic, we focus on each of the training principles and how and when to apply them. You will learn:

- Specificity

- Overload

- Adaptation

- Individualisation

- Reversibility

- Rest and recovery

- Maintenance

- Ceiling (flatlining)

- Variety

- Interference.

Terminology and vocabulary reference guide

As an allied health professional, you need to be familiar with terms associated with basic exercise principles and use the terms correctly (and confidently) with clients, your colleagues, and other allied health professionals. You will be introduced to many terms and definitions. Add any unfamiliar terms to your own vocabulary reference guide.

Activities

There are several practical activities in the topic and an end of topic automated quiz. These are not part of your assessment but will provide practical experience that will help you in your job and help you prepare for your assessment.

Before we get into specificity (and the other training principles) we need to have a good understanding of what is meant by fitness training overall.

Fitness is the ability to make enough energy to meet demands being placed on the body and as a personal trainer. You need to know the components of physical fitness and how your training programmes affect them. Fitness training is essentially a matter of replicating the movements and energy systems involved in that sport or physical activity. Fitness training is meticulous, grounded in science but allows a large degree of creativity.

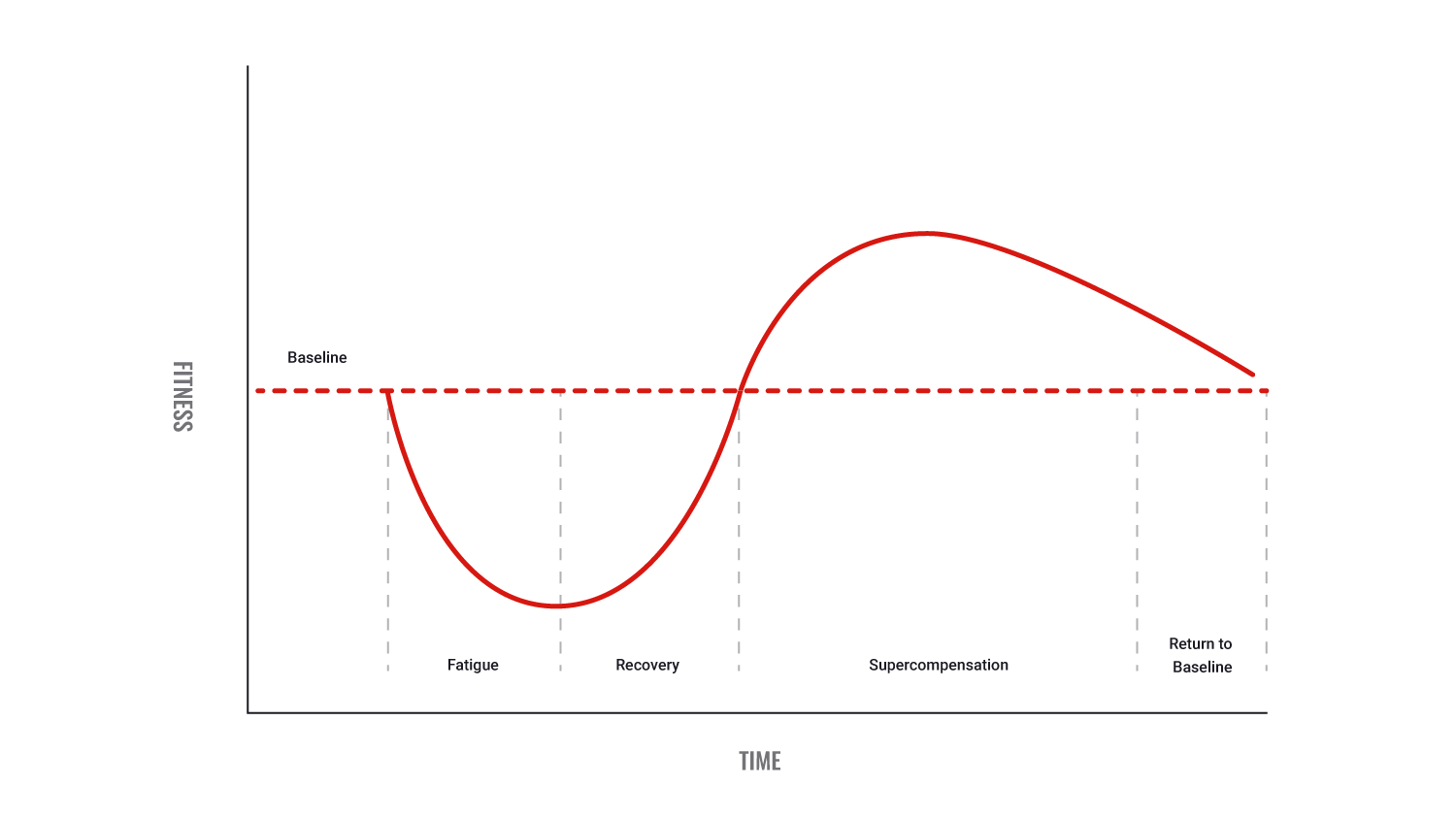

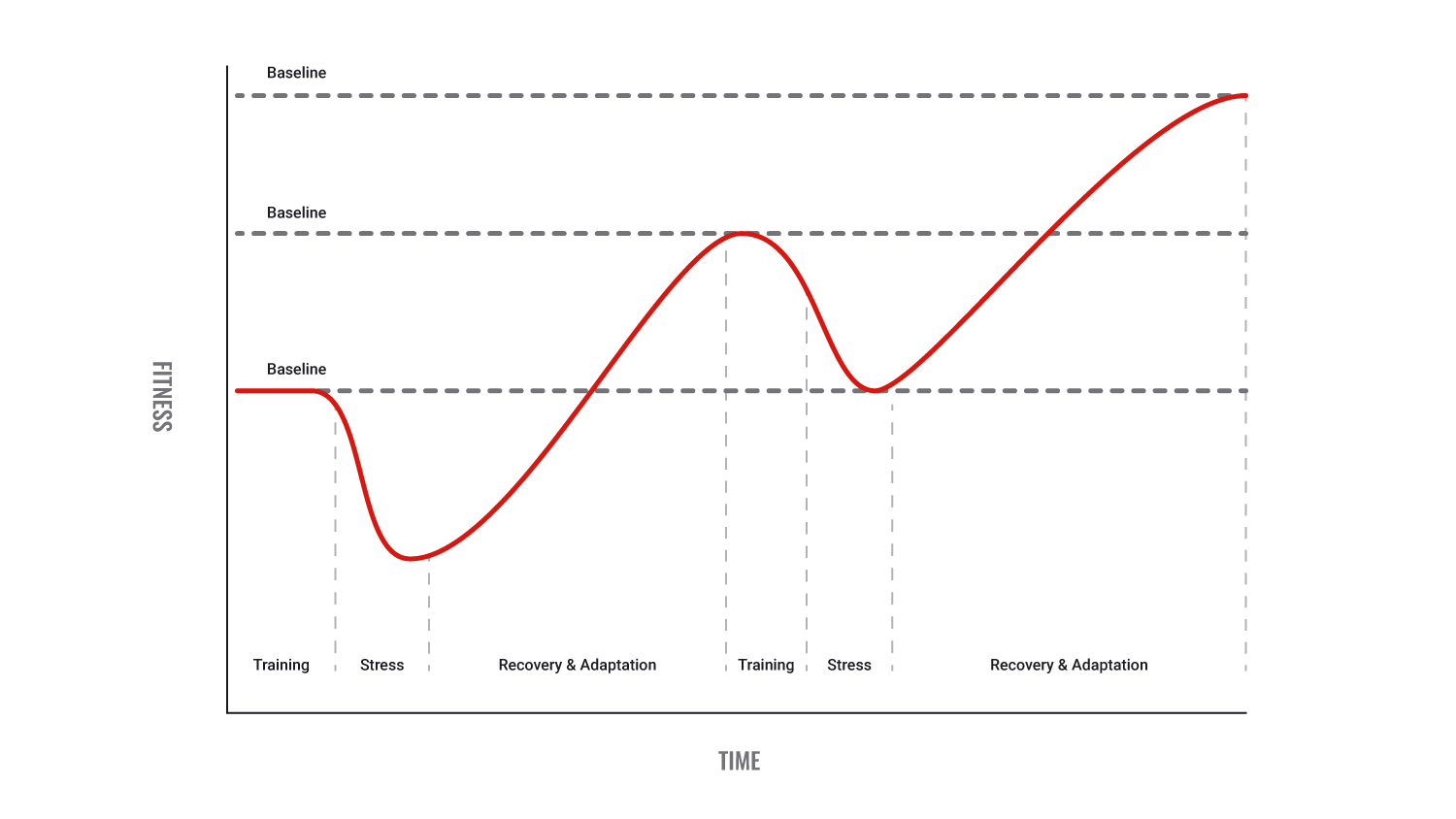

How does the body adapt to exercise? Let's think about how the body adapts to exercise as this is directly related to the specificity principle. Study the following diagram that illustrates the general adaptation syndrome and recovery to super-compensation (shown by the red curve). Then read the explanation that follows.

Explanation

- The general adaptation syndrome illustrates how the body adapts to stress. For our bodies, exercise is seen as acute stress that needs to be 'survived' or overcome.

- For example, the horizontal red line represents your current equilibrium or baseline level of fitness. When you do an exercise session you will notice the line drops down into the negative (fatigue).

- After the exercise session is over your body tries to overcome and recover from the stress of exercise over hours or days. You will then see the curve extend above the original baseline (super-compensation) into the positive, this represents improved fitness.

- If you add another exercise stress you repeat the process with a larger super-compensation. When you do repeated workouts your fitness will improve in a systematic manner. This is especially so if you train while in the super compensation period (within reason).

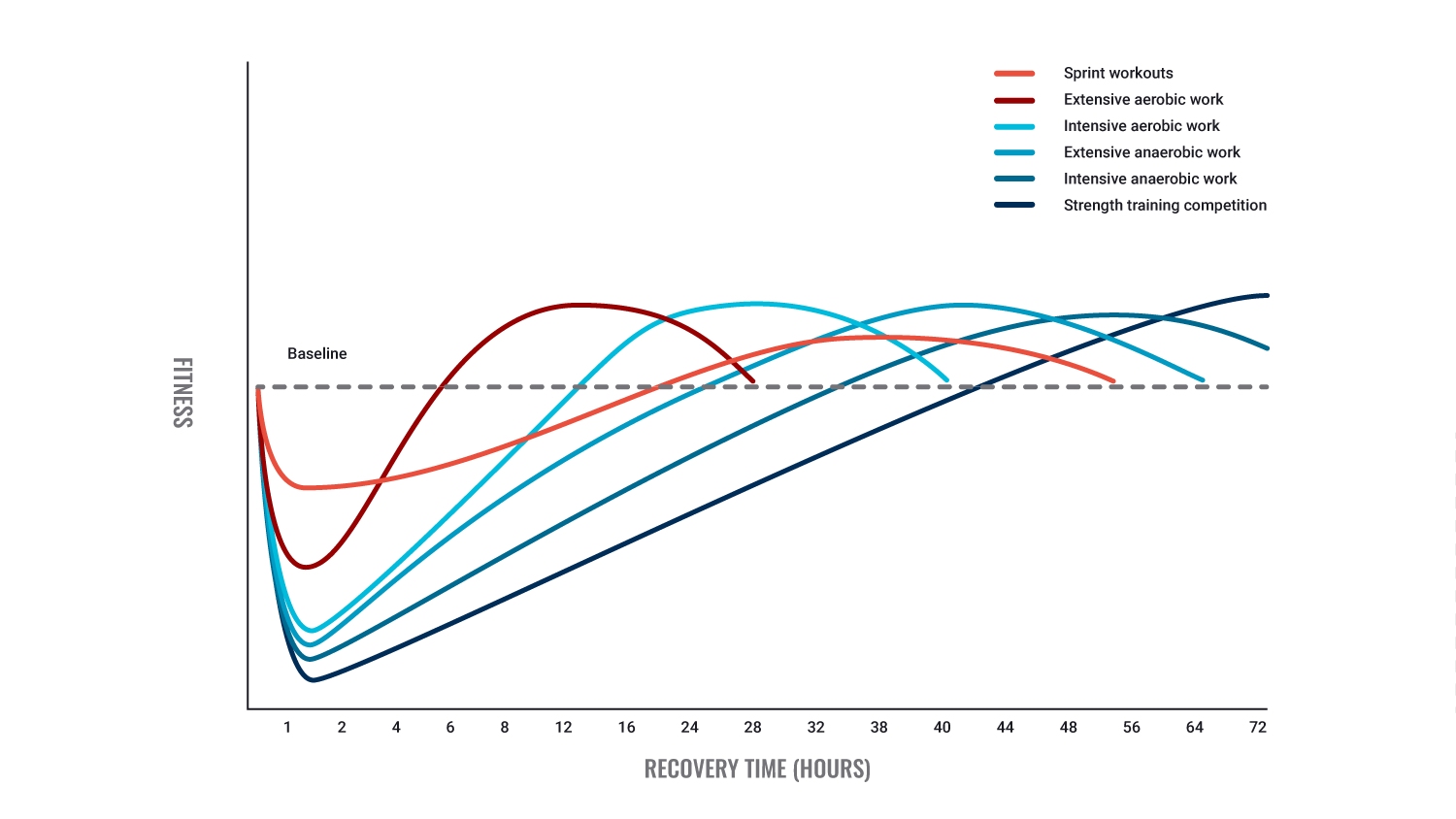

The key to training success is gauging what time is appropriate to add the next workout when it is above, not still below the baseline. Continuing competing workouts before full recovery has occurred will cause poor training adaption, burnout, fatigue, and possibly 'de-training' where you actually undo some of the good work you have achieved so far. So timing and rest is hugely important. Look at the following graph which shows recovery times and then read the explanation.

Explanation

The graph shows approximate recovery times for different types of workouts in hours. You will see you recover very quickly from extensive aerobic work (long slow distance) and slowly from very intense anaerobic work. Note the following:

- Extensive aerobic work targets regeneration.

- Intensive aerobic work targets aerobic capacity

- Extensive anaerobic work targets anaerobic capacity

- Intensive anaerobic work targets aerobic and anaerobic power.

- Aerobic and anaerobic power

The following table provides additional information that explains the incremental improvements to each type of workout.

| Training types | From | To |

|---|---|---|

| Extensive endurance | 8 | 12 |

| Intensive endurance | 24 | 30 |

| Sprints/short sets | 30 | 40 |

| Extensive anaerobic training | 36 | 48 |

| Extensive strength training | 40 | 60 |

| Intensive anaerobic training | 40 | 60 |

| Intensive strength training/competition | 48 | 72 |

Now let us look at each of the training principles in more detail

What is the specificity principle?

The specificity principle is the first (of a few) keys to developing effective fitness training programs, i.e., ones which are based around the client's goals and aims. Specificity refers to the type of changes (adaptations) the body makes in response to sports training, this adaption or change of the body or physical fitness is specific to the type of training that has been completed. Very simply, what you do is what you get. This principle of specificity sounds like it is on the tin, the adaptation to the body or physical fitness will reflect the type of training. The results of a training program are very specific to the task you do in that training program. For example, if you do strength training, evidence of your adaptation will be your ability to lift more. At the same time, you will not get any cardiovascular adaption. On the flip side, if the goal is to increase flexibility, this would be a huge component of the program, there would be little point in including weight training for example.

Applying specificity to a training programme

Specificity forms an integral part of both the advice you give and every program you design, if there is no purpose to what your clients do, they will not meet their goals which is the point of their training regime. For example, consider you are working with a volleyball player who wants to increase her vertical jump. With the aspect of specificity in mind, you should consider factors such as the key muscle group(s) required to perform a vertical jump, assess what her current jump style and ability to perform this movement currently are (consider this her baseline level in this action), and then establish what aspect of her current vertical jump ability need to be trained in order to see an improvement?

Progressive overload is not a new concept, in fact, a perfect example of this can be seen, and to this day remains a solid example of progressive overload. The 6th century BC saw a Greek athlete named Milo of Croton who competed in the ancient Greek Olympics and was well known for his incredible strength and wrestling prowess. Legend has it he achieved his strength by lifting carrying a calf each day from its birth until it became a mature, full-sized ox. Milo is renowned for his success in wrestling, earning the title of six-time champion at the ancient Olympic Games in Greece along with other champion titles. These days, in the 21st century, what we can take from his example is how Milo developed his strength. This is a perfect demonstration of progressive overload!

Progressive overload is when the workload you programme for a training session progressively increases as the client or athlete adapts to the training. For example, you may start an athlete preparing for a marathon on a five km run of medium intensity and move to a ten km run over time. Increasing the workload (or overload) is usually done to maintain the same intensity of training after the adaptations have occurred. Typically, it is best practice to change only one variable at a time to be able to accurately account for adaptations and observations made during training.

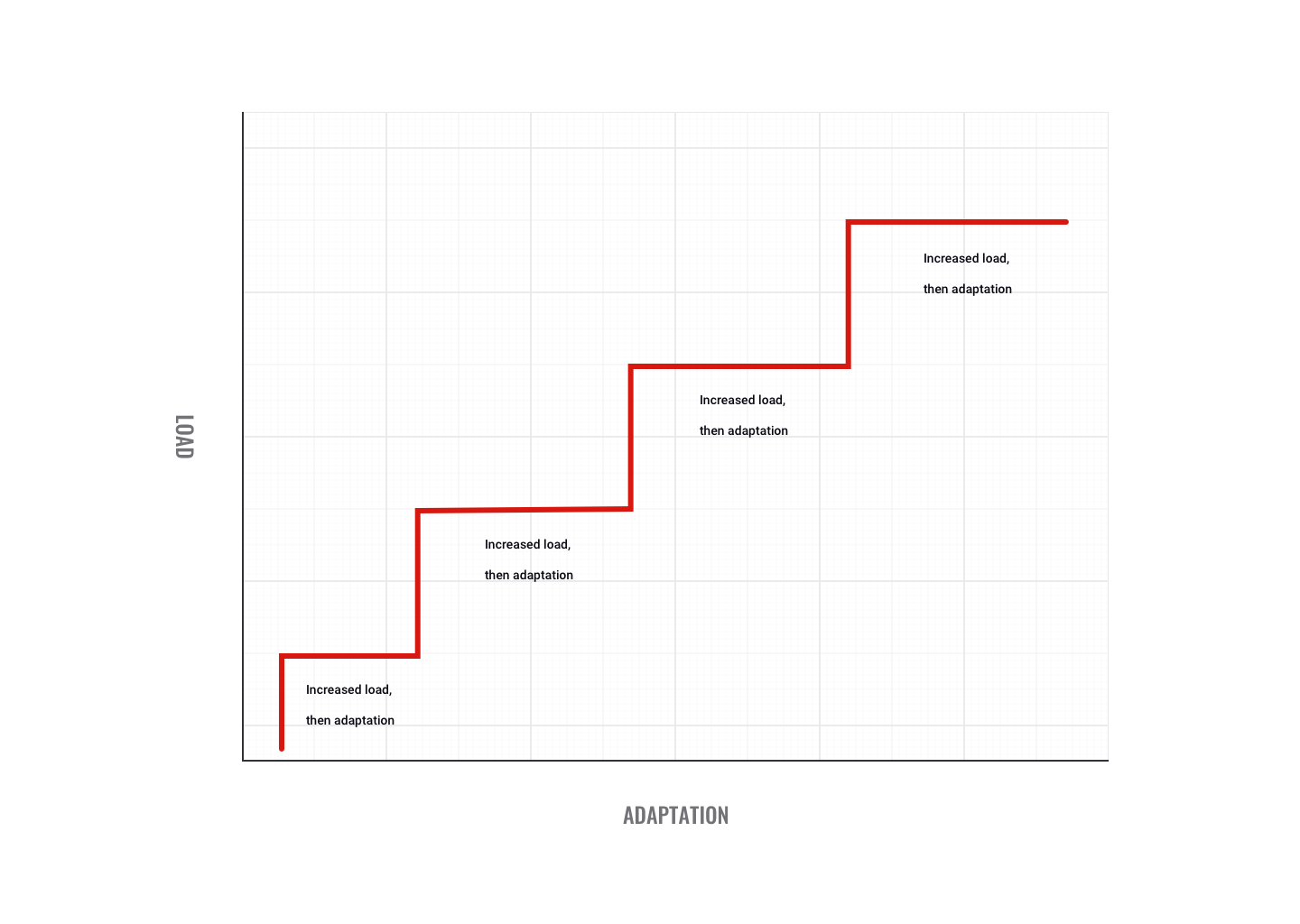

Study the following graph which shows the progressive nature of the overload principle and then read the explanation.

Explanation

- This must be a gradual and progressive process because too much overload can lead to injury and fatigue.

- To be effective, you need to have a client exercise at a level above normal and to create adaptations that cause the body to function more efficiently (overload).

- An appropriate overload for each person can be obtained by manipulating the frequency, intensity, and duration of exercise sessions. Gradually increase the training load and intensity from easy to difficult.

The training principle adaptation is linked to progressive overload. Adaptation refers to the process of the body adapting or becoming accustomed to a certain training technique or exercise through repeated exposure to the techniques or exercises. There are different phases of adaptation that the body will experience which are shown in the following graph.

Explanation

The body's response is an adaptation, which is your body's physiological response to training. When you do new exercises or load your body in a different way, your body reacts by increasing its ability to cope with that new load.

This graph shows the relationship between progressive overload and adaptation. The curve is essentially a repeated version of what we saw in progressive overload, simply repeated with increased improvements in fitness. Be mindful however, this progressive overload is applied when the body has already 'mastered' what has already been asked for it and is ready to process a new stimulus.

The fourth principle is individualisation. This focuses on the fact that training should be adjusted in relation to factors such as age, gender, stage or training, progress, injuries, health conditions, and previous skills development of the individual taking part in the program. The goal of individualisation is essentially to work with a client's strengths whilst building their 'weaknesses'. Training programmes need to cater to the individual needs and preferences of each client. This may also mean changing your communication styles to cater for people in the general community who may not speak English as their first language and may not speak 'exercise'.

The following factors need to be considered when individualising a program:

- Tolerance

- Training needs.

| Factor | Description |

|---|---|

| Tolerance to training | Some athletes respond to harder training than others. However, this does not guarantee that the most tolerant trainer is going to be the best performer. |

| Training needs | As a coach or trainer, it is important to have a profile of each athlete, this way strengths and weaknesses can be detected |

If you don't use it you lose it.

The fifth training principle reversibility states any fitness gains you make above your original baseline will gradually be lost once you stop adding appropriate training stimulus. Detraining can occur when:

- you totally stop training

- your training is not regular enough.

Consider this scenario. Imagine you only train once per week on a Monday. By the time the next Monday rolls around any gains have likely reverted back to close to, or at your original baseline (never mind it taking a long time to reach any goals). A minimum training regime of three times per week is recommended because the exercise stimulus is regular enough to prevent any detraining between workouts. As a general rule of thumb, you lose about 1% of your fitness gains per day after the first week of detraining.

Rest and recovery are essential components of a successful training programme. Exercise gains require a balance between rest and play. Fun fact: Gains are actually achieved when out of the gym rather than when in it. Unless a client has sufficient recovery periods, adaptations to training will not occur and the risk of injury will increase. The length of recovery needed may depend on the client's fitness level, training load (intensity, duration, type, and frequency), nutritional factors such as diet, work, and family commitments, sleep patterns, and so on.

There are two ways you can remember the rest and recovery principle shown in the following table.

| REST model | 4 Rs of recovery model |

|---|---|

|

Repair Eat Sleep Time |

Refuel Rehydrate Repair Relax |

The sixth training component is maintenance. Maintenance is achieved following a progressive base of training and a plateau has been reached. At this point it is not the individual's goal to improve further, just to keep or maintain the level of fitness they now have. Once a plateau has been reached the individual only has to do 30% of the training needed to get to this point in order to maintain their fitness. Fitness can be maintained by altering the variables of the FITT principles. One key point to note, when considering which variable(s) to manipulate is progress achieved to date, in order to preserve progress achieved to date, the intensity of the training must remain the same. The volume of training, however, can be significantly reduced, but intensity must remain the same in order to avoid regression.

Maintenance phases can also be useful when clients are juggling different training types. For example, opposing training adaptions such as strength training and endurance training can interfere with each other if done at the same time. One way to overcome this is by alternating maintenance phases:

- develop strength while dropping your endurance training by 50-60% for three weeks

- alternate to training endurance hard and maintain strength with a 50-60% drop in volume.

Imagine the following scenario. Reuben and his partner have been your clients for six months. They have a holiday coming up and Reuben admits to you they don't train much when they are on vacation. You discuss the options with Reuben and agree to work them hard leading up to the vacation then put them on a maintenance program while they are away. This could drop training volume by up to 70% but maintain their current level of fitness so when they come back they are not back at square one. Alternatively, they may erk at the idea of training whilst on holiday, and may not be aware that this would lead to a difficult re-entry into their training when they return. This links back to Principle 5: Reversibility; if they don’t use it, they lose it.

Don’t be afraid to explain the science to clients because understanding brings comfort and trust, and with trust comes acceptance. In other words, if the client understands why you are saying what you are and your rationale, they are more likely to be on board. This leads to client retention; if they feel comfortable with you, they’ll stay with you.

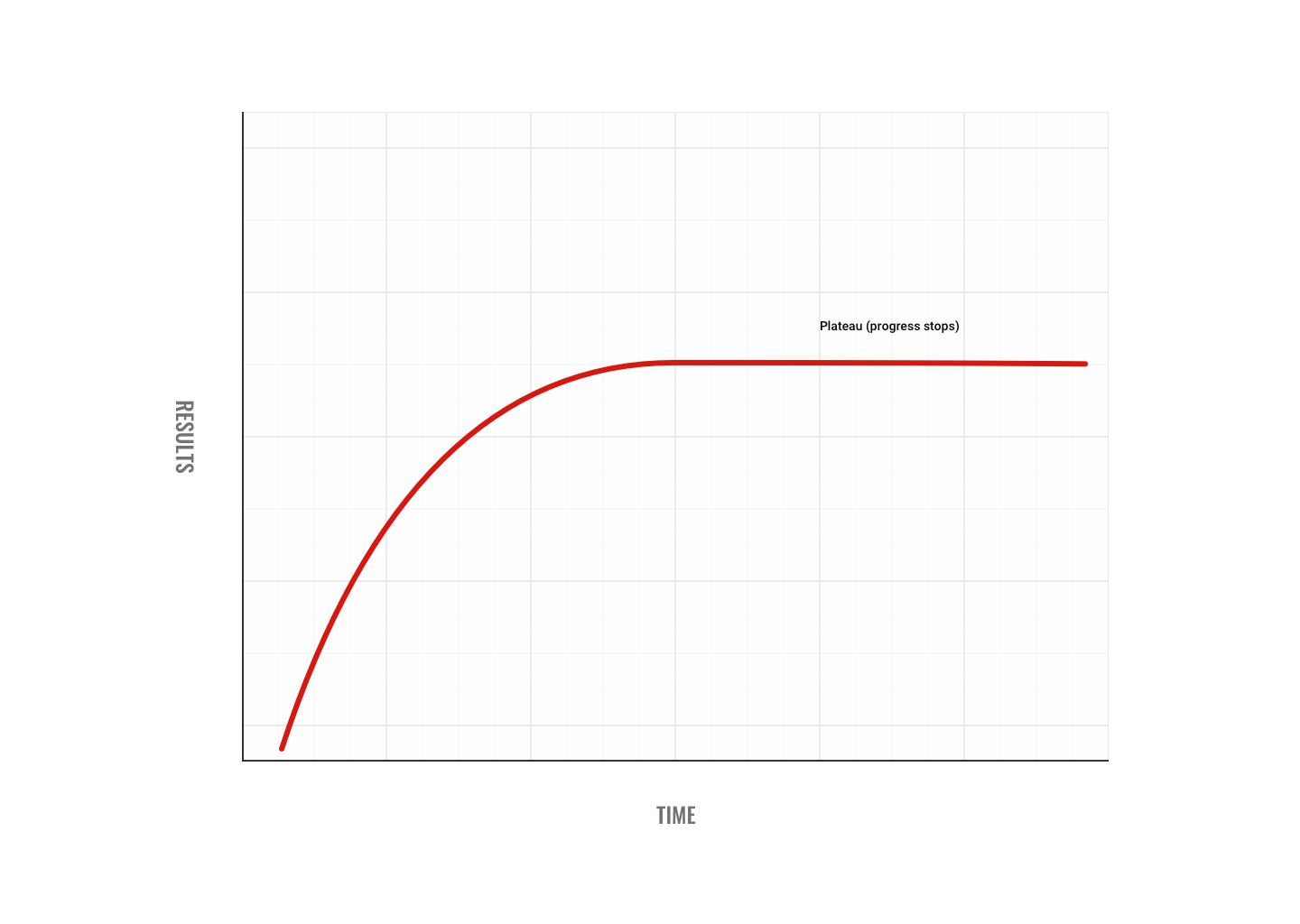

Room for positive development decreases the fitter you become!

Every client will reach a ceiling (or plateau) in their training where further increases in fitness or performance diminish or stop. There is only so much one human is capable of! Each of us has a genetic potential beyond which no increase in training will lead to further adaptation. As a client gets fitter, the amount of possible improvement decreases based on the client getting closer to their genetic potential.

This can also be applied to an individual training session. There is only so much stimulus our body can process before it needs a break. Therefore there is only so much the body can take from a training session before the session begins to lose effectiveness and the additional time in the gym serves little purpose. This comes down to training design and exercise selection. For example, this is why cross-fit sessions are typically 15-30 minutes; this is due to the nature of their comprehensive and high stimulus design. This is also why, typically, 60 minutes of a training stimulus is sufficient. There is no need for two-hour gym sessions!

Look at the following graph and read the explanation that follows.

Explanation

- With any training program and client, gain made early in a training program come very quickly because they are a long way from their genetic ceiling or potential, however as they improve, gains become harder and harder to achieve.

- They will need new and innovative training ideas to spark further adaptation. This is one of the main reasons why intermediate level clients seek the support of a personal trainer!

It is true, variety is the spice of life. It is also the spice of an effective training program!

We have discussed when and why the FITT principles are varied, but it doesn’t stop there. The principle of variety considers a variety of exercise stimuli, which is another factor to consider when achieving optimal adaptation and progression and avoiding overuse and risk of injury. As with other aspects in life, if we as humans do it for too long we become bored, slow down, make mistakes, and can become disengaged.

Our muscles (and neurological system) are much the same, and changing up their stimulus every so often keeps them on their toes (so to speak). A change is as good as a rest they say and a recovery of sorts from day-to-day activity. The same is true for muscles where variety allows for recovery. Resting a muscle or group of muscles, an exercise pattern, or an energy system allows recovery whilst shifting the focus elsewhere for a period of time.

However, this does not mean changing the exercises or exercise stimulus in every session. Each principle, whilst described individually is carefully considered along with the others. This means that a gradual and timely variation of exercise stimuli is more effective (and safe). Look for signs your client is becoming competent in performance and technique and is starting to feel their exercises are 'easy'. Remember, this can be a subjective report, so use your exercise knowledge to judge their readiness for change.

The final principle is interference. Interference occurs when two different forms of training occur simultaneously and the benefits or adaptations for each clash. This is illustrated by the following scenarios.

- Your client Joe is a semi-professional athlete who wants to combine strength training with endurance training. Both training methods have different training adaptations which will interfere with each other and affect the level of performance he achieves in strength and endurance. The key is ensuring there are sufficient days between strength and endurance training. Ask Joe which of the two would be his preferred focus and decide together the design focus of the programme. You may find one preference is really a wish, not a need, and in fact for his next season, one may be a greater focus than the other.

- Caterina is keen to train in hypertrophy and cardiovascular endurance at the same time. We know that to gain mass you need a surplus of calories to grow muscles, while on the other hand cardiovascular training consumes large amounts of calories which would otherwise go to building muscles. There is a clear and obvious interference at play here. Explain this to Caterina and work together to achieve an optimal and effective program design.

As a fitness professional, you are equipped with the knowledge and the skills to be amazing. Wow clients with your knowledge of the science behind exercise and share this with them. As a professional, you need to explain training principles in a way in your client understands. In doing this you will achieve confidence and trust and your client will be taken on their training journey too as opposed to being left behind in the jungle of science.

Developing a programme based on training principles

Imagine you have a new client who is an athlete in training for a triathlon in eight weeks. He has asked you to prepare a training program for the running part of the event. With the knowledge, you have learned so far, consider the aspects mentioned below and think about how you would approach creating a training plan based on the training principles.

- Specificity

- Progressive overload

- Adaptation

- Individualisation

- Reversibility (detraining)

- Rest and recovery

- Maintenance

- Ceiling or plateau

- Variety

- Interference.

In this topic, we focused on each of the training principles and how and when to apply them. You learnt:

- Specificity

- Overload

- Adaptation

- Individualisation

- Reversibility

- Rest and recovery

- Maintenance

- Ceiling (flatlining)

- Variety

- Interference.